Introduction

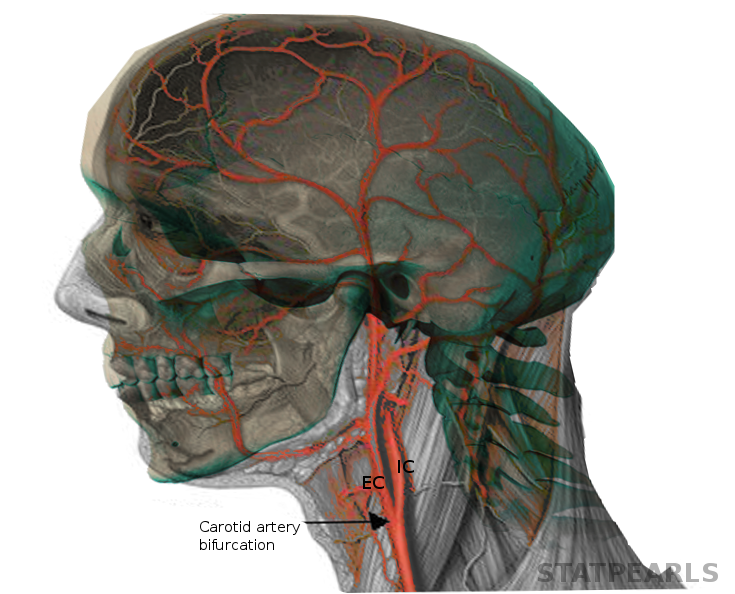

The head and neck region obtain the majority of its blood supply via the carotid and also vertebral arteries. This activity primarily focuses on the in-depth orientation of the carotid arteries, including their anatomical course, branches and also the area of distribution. The carotid arteries are the primary vessels supplying blood to the brain and face.[1][2] The right common carotid artery (RCCA) originates in the neck from the brachiocephalic artery while the left common carotid artery (LCCA) arises in the thorax from the arch of the aorta.[3] Furthermore, both right and left common carotid arteries bifurcate in the neck at the level of the carotid sinus into the internal carotid artery (ICA), which supplies the brain, and the external carotid artery (ECA), which supplies the neck and face.[3]

Structure and Function

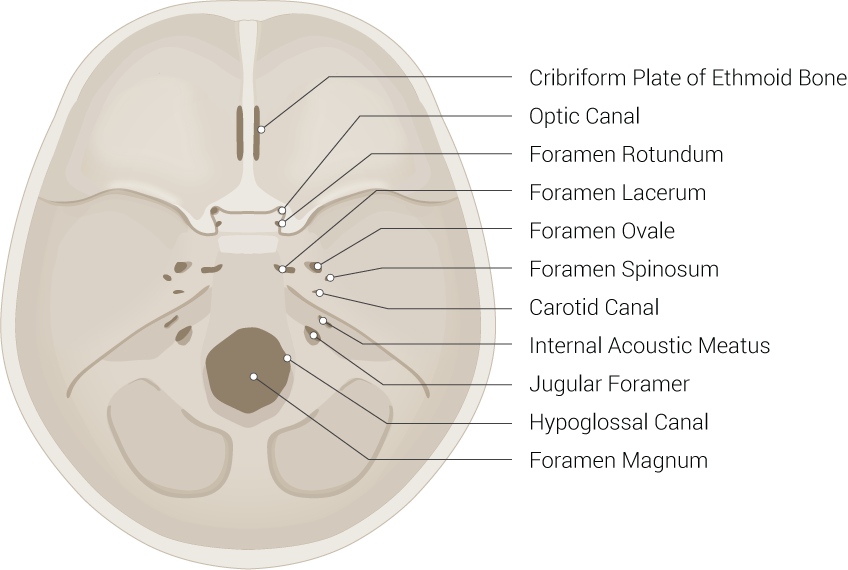

Like most of the vascular system throughout the body, histologically, the carotid arteries are made up of three layers – the inner layer "tunica intima," the middle layer "tunica media," and the outer layer "tunica adventitia." The tunica intima consists of endothelium supported by a fragile elastic and also a collagenous layer of variable thickness. Smooth muscle comprises the tunica media, and it is responsible for changing the diameter of the blood vessel to regulate blood flow and blood pressure. The tunica adventitia attaches the carotid vessel to the surrounding tissue. The carotid arteries originate posterior to the sternoclavicular joints and in the neck, they are contained within the carotid sheath posterior to the sternocleidomastoid muscle. At the location of the upper border of the thyroid cartilage (typically at the level of the fourth or fifth cervical vertebra), the common carotid arteries bifurcate into the ECA and ICA. This bifurcation point is clinically significant as it serves as a point for the location of the "carotid body," a chemoreceptor, and the "carotid sinus," a baroreceptor. The carotid body chemoreceptor is sensitive to decreased PO2, increased PCO2, and decreased pH of blood, and is responsible for alerting the brain to change the respiratory rate. The carotid sinus baroreceptors respond to changes in the stretch of the blood vessel and are responsible for detecting changes and maintaining blood pressure. After its division, the ECA exits the sheath to provide oxygenated blood to the face and neck, while the ICA continues in the carotid sheath to enter the carotid canal within the temporal bone.

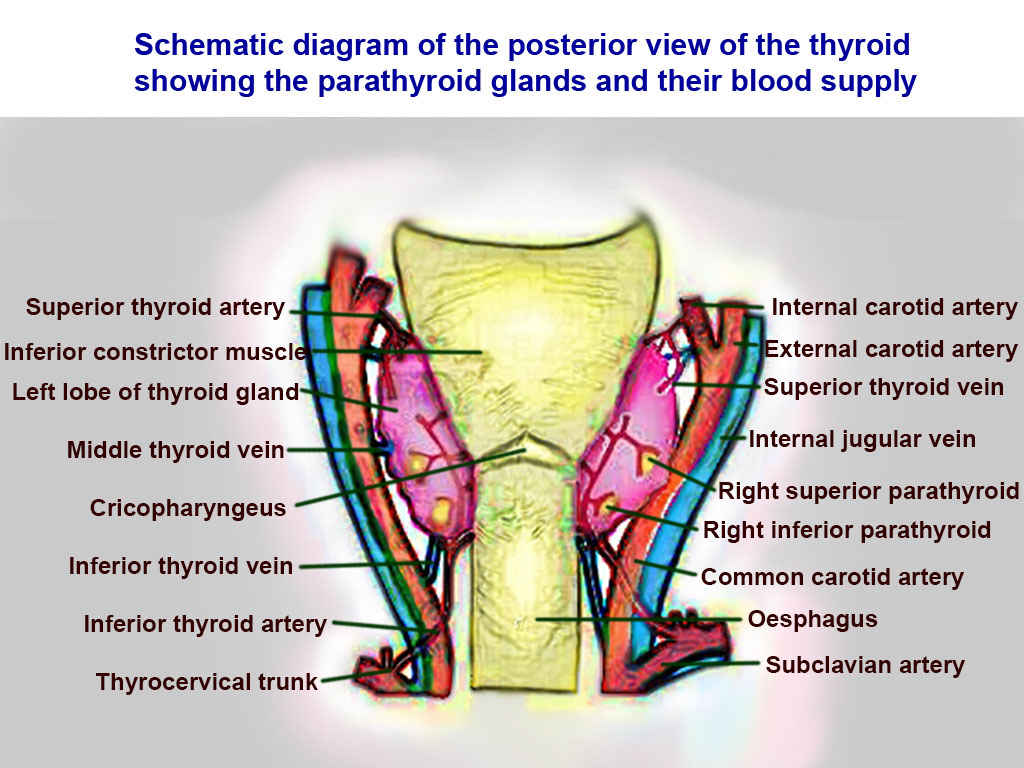

The ECA has eight branches, which anastomose with the branches from the contralateral external carotid, allowing for collateral circulation: These branches include

- Superior thyroid artery

- Ascending pharyngeal artery

- Lingual artery

- Facial artery

- Occipital artery

- Posterior auricular artery

- Maxillary artery

- Superficial temporal artery

On the other hand, the ICAs anastomose with the branches of the basilar artery to form the circle of Willis. At the circle of Willis, the ICA branches to become the middle cerebral artery (MCA) and anterior cerebral artery (ACA). The MCA is responsible for supplying the motor and sensory cortices of the upper limb and face, as well as the Wernicke area of the temporal lobe and Broca’s area of the frontal lobe. The ACA is responsible for supplying the motor and sensory cortices of the lower limb. The ophthalmic artery is responsible for blood supply to the inner layers of the retina, as well as supplying other parts of the orbit, meninges, face, and upper nose.

Moreover, the course of the ICA is divided into four sections, depending on where the artery is currently traveling. These sections include the cervical, petrous, cavernous, and cerebral parts of the ICA. The ophthalmic artery branches off the cavernous portion of the ICA while the MCA and ACA are branches of the cerebral ICA.[4][5][6][7]

Furthermore, the neurologists, neuroradiologists, and neurosurgeons also use the Bouthillier classification to split the ICA into different parts based on the angiographic appearance of the vessel. According to this classification, the ICA slits into seven parts named as C1 to C7, with each part providing branching into different vessels. These branches of the ICA are generally tiny and inconsistent, and often they might not be present. However, the ophthalmic artery is present pretty much all of the time.[8] The description of this classification is below

- C1: Cervical

- C2: Petrous

- Caratiotympanic artery

- Vidian artery

- C3: Lacerum

- C4: Cavernous

- Meningohypophyseal trunk

- Inferolateral trunk

- C5: Clinoid

- C6: Ophthalmic

- Ophthalmic artery

- Superior hypophyseal trunk

- C7: Communicating

- Posterior communicating artery

- Anterior choroidal artery

- Anterior cerebral artery (ACA)

- Middle cerebral artery (MCA)

Embryology

The embryological devolvement of the carotid vascular system is very interesting. AS the pharyngeal arches begin to form during weeks 4 to 5 of gestation, the common carotid arteries (CCAs) and proximal ICAs derive from the third pharyngeal arch. While the distal ICA derives from the dorsal aorta. Interestingly, the ECA derives from the CCA via angiogenesis.[9]

Nerves

The glossopharyngeal nerve (CN IX) is responsible for transmitting baroreceptor afferent input from the carotid sinus to the solitary nucleus of the medulla. Also, the vagus nerve (CN X) runs posterolaterally to the ICA/CCA and posteromedially to the internal jugular vein within the carotid sheath.

Muscles

Understanding the vascular supply of the carotid arteries is crucial clinically. The muscles of mastication receive vascular supply from the maxillary artery and facial artery, branches of the ECA. The facial artery also supplies muscles of facial expression. The occipital artery, another branch of the ECA, supplies blood to the sternocleidomastoid, trapezius, and deep muscles of the back. The superficial temporal artery supplies the temporal muscle. The extraocular muscles get their vascular supply by branches of the ophthalmic artery, which is a branch of the ICA.[10]

Physiologic Variants

The common carotid artery typically bifurcates at the upper border of the thyroid cartilage, but several studies have shown a variant in which the common carotid artery bifurcates more distally. This bifurcation is significant as the carotid bifurcation is the site of clinically meaningful atherosclerosis and a more distal bifurcation may impact the ability to proceed with standard surgical approaches.[11]

Rare case reports have presented variants of ICA and ECA agenesis, aplasia, and hypoplasia, and these have been found to be both unilateral or bilateral. The COW usually supplies collateral circulation.[12] Another example of an aberrant ICA is a retropharyngeal ICA which is generally asymptomatic but is essential to recognize in the face of non-typical symptoms. Some symptoms could include submucosal pulsating mass in the posterior pharynx even hoarseness and respiratory issues depending on how medially located the ICA is.[13]

Surgical Considerations

The carotid arteries are vital for providing oxygenated blood to the brain. Just like all arteries, they are susceptible to atherosclerosis, which can lead to stenosis and distal embolism of plaque. Additionally, during aortic arch surgeries, perfusion to the brain must be maintained. Lastly, injury to the carotid arteries must be ruled out in penetrating neck traumas.

- Carotid Artery Stenosis: Atherosclerosis of the carotid arteries most often occurs at the bifurcation of the CCA to the ICA and ECA. This condition is one of the major causes of transient ischemic attack and stroke. The condition is usually manageable with optimized medical therapy, but there are two surgical treatment modalities for patients who are asymptomatic with high-grade stenosis (70 to 90%) or patients who are symptomatic with moderate (50 to 69%) or high-grade stenosis. Surgical options include an endovascular approach (angioplasty and stenting) and an open approach (endarterectomy). Several trials are underway to compare the efficacy of these two modalities, as well as comparing them to optimized medical therapy. There are risks and benefits with both approaches, so deciding which approach to use depends on the patient’s level of stenosis and other comorbidities.[14][15]

- Aortic surgery: During aortic arch repair, cerebral protection is necessary. There are several approaches, including hypothermic circulatory arrest, retrograde cerebral perfusion, and antegrade selective cerebral perfusion via the carotid arteries. One study uses existing evidence to propose hypothermic circulatory arrest and antegrade selective cerebral perfusion as the preferred approaches for neuroprotection during aortic arch repair; a retrospective review later supported this approach.[16][17]

- Penetrating neck trauma: If a patient with penetrating neck trauma becomes unstable or presents with hard signs, such a condition warrants surgical exploration. Hard signs that would be concerning in regards to the carotid artery include diminished carotid pulse, expanding hematoma, and active arterial bleeding. Injury to the carotid occurs in 4.9 to 6% of penetrating neck traumas. Attempts should always be made to repair the artery due to better rates of survival and lower risk of permanent neurologic deficits. Repair options include primary repair, anastomosis, vein grafting, PTFE patch, and transposition of ECA to injured ICA. Ligation of the artery is necessary when a repair is not possible but has higher rates of mortality and morbidity, such as stroke.[4][18]

Clinical Significance

The common carotid artery can be used to measure the pulse. In the setting of hypovolemic shock, if only the carotid pulse is palpable, this correlates to a systolic blood pressure of 60 to 70 mmHg. As the carotid arteries are responsible for supplying oxygenated blood to the brain, many conditions require monitoring and treatment, especially if the patient is symptomatic, including atherosclerosis leading to stenosis, carotid artery aneurysm, transient ischemic attack, and stroke.