Continuing Education Activity

A cardiac contusion is a misnomer used to indicate injury to the heart after blunt chest trauma. Because of the term's ambiguity in describing a spectrum of myocardial injuries secondary to blunt trauma, "cardiac contusion" is now termed "blunt cardiac injury." Blunt cardiac Injuries can range from clinically silent, transient arrhythmias to fatal cardiac rupture. This activity describes the etiology, epidemiology, and management of blunt cardiac injury. It explains the role of an interprofessional team in the evaluation and management of such patients.

Objectives:

Describe the risk factors for blunt cardiac injury.

Outline the diagnostic techniques for blunt cardiac injury.

Explain the conservative and invasive treatment options and their indications in the treatment of patients with blunt cardiac injury.

Describe the interplay among the interprofessional team in rapidly diagnosing, treating, and rehabilitation of patients with blunt cardiac injury.

Introduction

[1]The term “cardiac contusion” has been used to describe an injury to the heart after blunt chest trauma.[2] Histologically, it is characterized by a contused myocardium with hemorrhagic infiltrate, localized necrosis, and edema. Findings are best confirmed during surgery or at autopsy.[3] Clinically, blunt cardiac injury (BCI) is the preferred diagnosis term, as blunt chest trauma can result in a broad range of cardiac injuries. [4][5] BCIs can be further described by specific injuries or observed dysfunction.[6] Significant BCI usually occurs from high-impact trauma from motor vehicle accidents (50%), pedestrians struck by motor vehicles (35%), motorcycle crashes (9%), and falls from significant heights (6%).[7][8][9] Diagnosing BCI can be challenging as there is no accepted gold standard diagnostic test. The diagnosis is fraught with further difficulty in the polytrauma patient. The reported incidence of cardiac injury following blunt chest trauma ranges from 8% to 76%, in large part due to a lack of standardized diagnostic criteria.[9]

In the absence of severe arrhythmia and hemodynamic instability, the significance of BCI is sometimes called into question.[7][10] In the setting of blunt trauma, a high clinical suspicion for BCI is required, and certain patients should be monitored for adverse sequelae since there are no pathognomonic clinical signs or symptoms that correlate with the risk of cardiac complications.[7][11][12] Indeed, the sequelae of BCI are more important than its label.

Etiology

Blunt cardiac injury (BCI) from blunt chest trauma is most commonly due to motor vehicle collisions (50%), with 20% of all motor vehicle collision deaths involving blunt chest trauma.[4] Other mechanisms such as falls, blast injuries, assault, and other blunt mechanisms also play a role.[2] The mechanism and magnitude of force determine the cardiac injury sustained. With enough force, the heart can be compressed between the sternum and spine. Deceleration injury may tear the heart from its attachments. Most often, these types of injuries are not survivable, and patients typically expire in the field. Although BCI may be associated with injuries to nearby structures, including the thoracic aorta, lung, rib, sternum, and spine, none are necessarily indicative of BCI and can only raise one's index of suspicion.[8]

Epidemiology

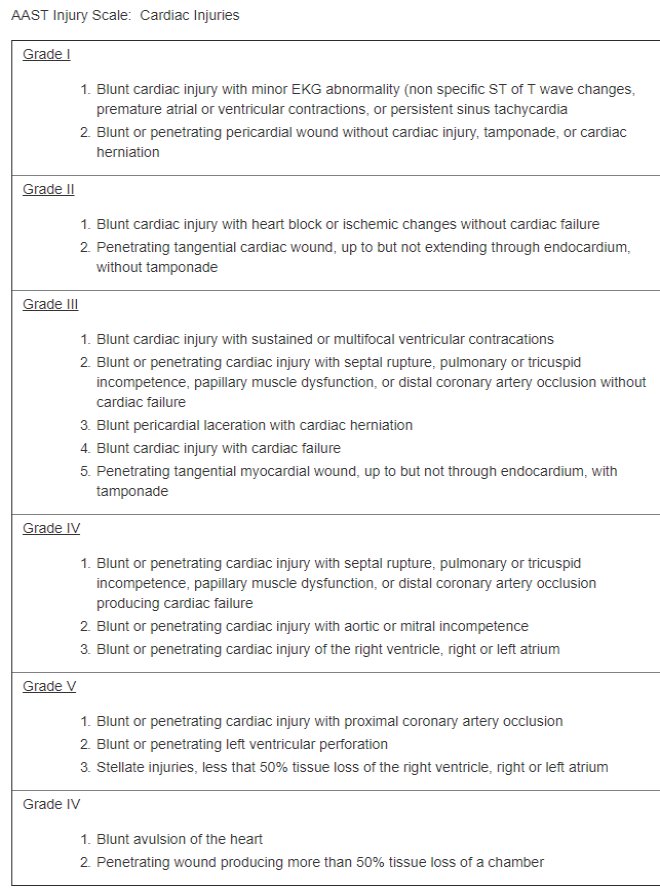

In the United States, trauma is the 4th leading cause of death. The incidence of blunt cardiac injury (BCI) has a broad range due to a lack of widely accepted diagnostic criteria, inconsistencies in reporting, and a lack of consensus on its definition. Diagnosis can be mistaken when symptoms are misattributed and not related to BCI. For example, an arrhythmia may simply be a pre-existing condition. Furthermore, diagnostics, including elevated troponins, can be due to trauma unrelated to the chest.[13] The American Association for the Surgery of Trauma (AAST) developed the AAST Cardiac Injury Scale that applies to blunt and penetrating cardiac injuries for grading purposes (see Table. The AAST Injury Scale, Cardiac Injuries). Note: When using the table, advance one grade for multiple penetrating wounds to a single chamber or multiple chamber involvement.

Pathophysiology

Six potential mechanisms have been suggested for BCI: direct, indirect, bidirectional, deceleration, blast, crush, concussive, or combined.[2][4] Direct impact to the chest is considered the most common mechanism, and cardiac injury is most likely when the ventricles are maximally distended at the end of diastole.[7] An indirect increase in preload by way of abdominal or extremity veins can result in a sudden increase in the intracardiac pressure, thereby making the heart susceptible to rupture.[7] Bidirectional forces result in compression of the heart between the spine and sternum.[7] Deceleration mechanisms may result in tears to valvular structures, the myocardium, or coronary arteries.[2][7]

The cardiac chamber injury distribution reflects the position of the heart in the chest, where the right ventricle and right atrium are more anterior compared to the left ventricle and left atrium.[7][14]. The most common cardiac injuries from blunt trauma resulting in death are due to cardiac chamber rupture (64%), venous-atrial confluence tears (33%), coronary artery tear or dissection, or a combination thereof.[8] Of note, commotio cordis is sudden death due to cardiac arrest from BCI in the absence of preexisting disease and with no morphological injury to the heart at autopsy. It is usually seen in the young male athlete. It is thought that ventricular fibrillation occurs as a complication of impact during ventricular repolarization.[4][8]

Most patients who survive BCI have less severe injuries that range from structural injuries to electrical and conduction disturbances.[8] An intramural hematoma is one such structural injury that, for the most part, has a benign clinical course that resolves in 4 to 12 weeks. It can cause premature ventricular contraction (PVC) and transient bundle branch block (BBB). Another common structural injury is papillary muscle rupture which can lead to regurgitation of the valves and may require repair.[8] Septal injuries can present with a murmur or arrhythmia on an electrocardiogram (ECG). The course of this injury begins with contusion followed by necrosis and then delayed rupture. Hence, early diagnosis is important as the injury may be treatable.[7][8]. The most common dysrhythmia in BCI is sinus tachycardia, followed by premature atrial or ventricular contractions, atrial fibrillation, and BBBs.[4][8] Tachycardia in the trauma patient should raise greater suspicion of ongoing bleeding than BCI. Once bleeding is ruled out, BCI becomes more probable in the differential diagnosis.

History and Physical

It is important to first identify the trauma patient with blunt chest injury by the mechanism of force. For instance, patients involved in an MVC should be queried on whether there was a steering wheel impact. In one study, 54% of patients with a history of a fall greater than 20 feet had BCI.[8]

The most common complaint is chest pain or shortness of breath[2][4], but some may report palpitations or even present with typical symptoms of angina.[4][15] It is also important to assess cardiac risk factors such as a history of myocardial infarction, cardiovascular disease, and other commonly associated comorbidities. Medication assessment is important, especially in the patient taking cardiac drugs, which can alter the patient's presentation. For example, beta-blockers and calcium channel blockers may mask tachycardia.

The physical exam should be thorough. Patients can present with cardiac tamponade, and suspicion should be high in the presence of jugular venous distention and hypotension. The focused assessment with sonography for trauma (FAST exam) will help in the assessment for pericardial fluid and cardiac tamponade. Tachypnea, irregular lung sounds, chest wall tenderness, chest abrasion or ecchymosis, rib or sternal fractures, and seatbelt sign across the chest are some of the physical findings that should raise suspicion for BCI[11], although they are non-specific.[2][4][11][15] Furthermore, patients with severe BCI are more likely to have other significant traumatic injuries that may mask or distract from some of its physical sequelae.[11][15]

Evaluation

No consensus has been established to diagnose blunt cardiac injuries. However, in 2012, the Eastern Association of Trauma (EAST) published BCI practice guidelines that supported obtaining an ECG in all patients with suspected BCI.[7][8] Patients with abnormal findings should be admitted for continuous cardiac monitoring; however, a normal ECG does not entirely exclude BCI, as it has been reported that a significant number of patients with an initial normal ECG were noted to have a possible cardiac injury 24 hours later as measured by elevated cardiac troponin I (cTnI) levels.[4][7] Nevertheless, patients with a normal ECG in conjunction with normal levels of cTnI can be safely discharged home.[4][7][8] Furthermore, it should be noted that normal ECG and cTnI levels do not rule out all BCI as some may have a delayed presentation (e.g., septal injury). Following an abnormal ECG and cTnI level, echocardiography is usually obtained to further characterize the injury. Computerized tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) do not play a role in the initial diagnostic evaluation of BCI; however, these modalities can be complementary or useful in the patient with symptoms without a clear clinical etiology and can be considered on a case-by-case basis.[4][7]

Treatment / Management

Patients with abnormal ECG and/or cTnI levels should be admitted for cardiac monitoring for 24 to 48 hours because life-threatening arrhythmias or cardiac failure will most likely present during this time.[4][15] Patients can be admitted to the intensive care unit or placed under telemetry, depending on concurrent injuries, type of ECG change, and the grade of hemodynamic imbalance. It is not necessary to admit all sternal fractures with a normal ECG to rule out BCI. The most prevalent of the BCIs are the subset of patients with isolated abnormal ECG and/or cTnI elevations which usually have a benign course with the rare occurrence of long-term functional impairment.[2]

Management of dysrhythmias should be approached and treated as in the non-BCI patient. Replete electrolytes accordingly, avoid hypoxia and acidosis, and when clinically indicated, utilize antidysrhythmics and advanced life support algorithms. Although rare with isolated BCI, complete heart block may necessitate a pacemaker. ST segment elevations can be due to either a contused heart or a traumatic myocardial infarction, necessitating coronary angiography.[4]

Patients with severe clinically diagnosed or imaged structural cardiac injury require emergent cardiology evaluation for further management. Temporizing measures such as fluid resuscitation, inotropes, or vasopressors may be indicated in the interim based on the specific clinical findings and associated injuries. Patients presenting with cardiac tamponade, most frequently seen in cardiac rupture, require emergent surgical intervention.[2][4] Cardiothoracic intervention is required, and time is of the essence in the majority of those cases. Refractory cardiogenic shock can benefit from an intra-aortic balloon pump (IABP) to help increase coronary blood flow, allowing the stunned heart to recover in days to weeks.[2]

Differential Diagnosis

- Arrhythmia

- Cardiac tamponade

- Cardiac wall motion abnormality

- Cardiogenic pulmonary edema

- Cardiogenic shock

- Hemorrhagic shock

- Myocardial infarction

- Valvular regurgitation

Prognosis

Prognosis in blunt cardiac injury (BCI) is highly dependent on the specified injury, its association with concomitant injuries, and any history of previous cardiac disease or injury.[15] The patient with isolated BCI that is presented by way of an abnormal ECG or cTnI level tends to have a more favorable outcome than the patient who is hemodynamically compromised with a cardiac structural injury with an associated high trauma injury score.[8][15] Given that the former represents the largest pool of BCI patients, BCI generally has a favorable prognosis overall.

Complications

Overall, complications from blunt cardiac trauma are rare.[8][15] Acute complications from severe cardiac injuries usually necessitate immediate management, and those that survive may have long-term complications related to their specific injury. Most BCI patients do not have long-term sequelae, but a few late complications have been reported, including delayed cardiac rupture, complete atrioventricular block, heart failure, pericardial effusion, and constrictive pericarditis.[8] Therefore, good practice entails reevaluating these patients in 3 to 6 months.[8]

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

The diagnosis of blunt cardiac injury (BCI) remains challenging due to its variable presentation and range of injury. Furthermore, there is a lack of consensus on the definition and diagnostic criteria. However, the crucial factor in caring for these patients is to have a high suspicion in trauma patients. ECG and cTnI levels can be used as screening tools, followed by admission and echocardiography for any resultant abnormalities, with the understanding that BCI can take up to 48 hours to manifest. An interprofessional consensus should be employed to identify BCI based on the specific injury.

While the majority of cases diagnosed as BCI may be inconsequential, the true significance of the diagnosis remains controversial due to inadequate assessment of long-term outcomes. Those suspected of having BCI who are hemodynamically stable without dysrhythmia should at least have a short period of observation. Further consensus and research among providers are warranted to better define the management and long-term significance of BCI.