Anatomy and Physiology

The EPS starts with the placement of bipolar or multipolar catheters in the heart for the acquisition of intracardiac electrical signals. These signals are properly amplified, filtered, digitized, and finally displayed along with standard ECG recordings. The intracardiac electrograms (EGMs) are broadly divided into two types: “unipolar” and “bipolar.” A unipolar signal is the recording of the voltage difference between an intracardiac (cathode, located at the tip of the catheter) and an extracardiac (anode, usually in the inferior vena cava located) electrode. On the contrary, bipolar signals are electrical activities recorded from one of the close-spaced (2 to 3 mm apart) electrode pairs of an electrophysiologic catheter within the heart cavity. In EPS, bipolar recordings are most commonly used because they are far less susceptible to the sensing of signals originating far away from the recording site (far-field signals) compared to unipolar recordings, which display a voltage difference over a large distance.

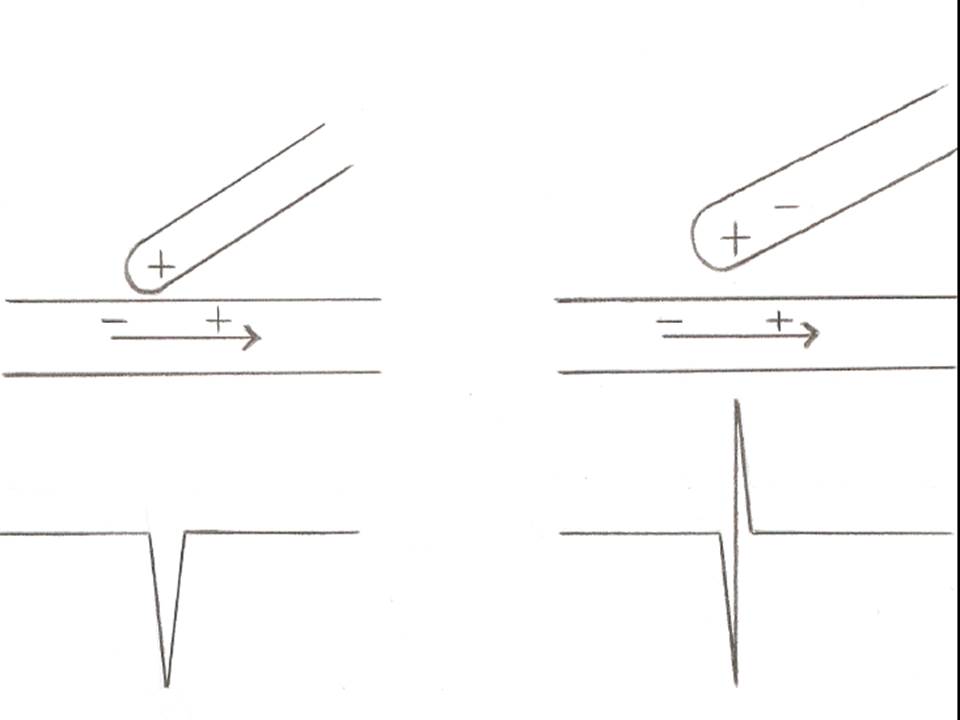

However, unipolar recordings are very useful when we want to accurately locate and ablate an arrhythmogenic focus. The reason is that a unipolar electrode records only one electrical impulse which passes through the point of contact with cardiac tissue, while a bipolar electrode displays the summation of two recordings each from the proximal and the distal pole of the of pair electrodes. Since a negative deflection is always inscribed when an electrical pulse is moving away from the recording electrode, a sharp negative unipolar signal denotes the point of origin of the impulse, which then spreads away to the rest of the myocardial tissue.[1] (Figure1)

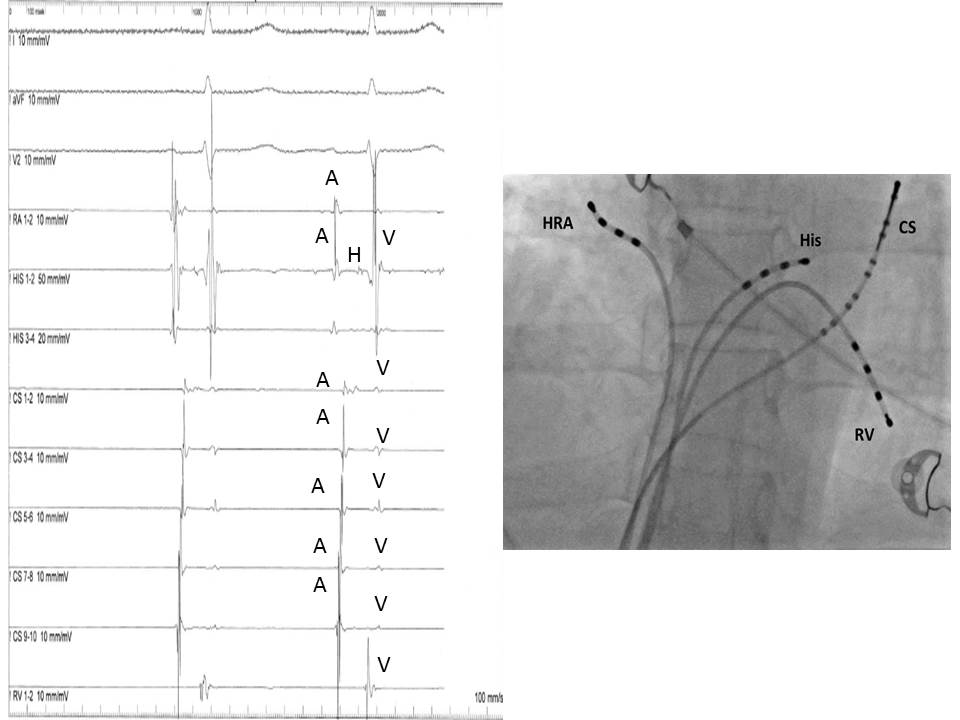

In a baseline EPS, the EGMs are usually obtained from catheters located in the following anatomical structures:

- High right atrium near the sinus node (HRA)

- His-bundle (His)

- Coronary sinus (CS)

- The apex of the right ventricle (RV)

The most common displayed format follows the sequence of the normal impulse during sinus rhythm and includes from top to bottom: two or three ECG leads (usually I, III and V1), HRA, His distal, His proximal, CS 1-10 and RV. (Figure 2)

Preparation

The patient must be fasting for at least six hours before the procedure. Antiarrhythmic therapy must be withheld for at least four half-lives. Hypoglycemic therapy must be appropriately adjusted. Anticoagulation therapy is usually interrupted before the procedure for 3 to 4 days for warfarin and 1 to 2 for novel anticoagulant regiments. "Bridging therapy" with low molecular weight heparin is generally not indicated.[5] On the other hand, uninterrupted therapy is an option with the novel anticoagulants.[6] However, the approach should be individualized, taking into account both the thromboembolic and the bleeding risk of the particular patient. Intravenous access should be secured before the arrival in the electrophysiology laboratory, and fluids should be administered during the procedure to avoid dehydration.

Upon arrival in the electrophysiology laboratory, the patient is connected to a 12-lead surface ECG (usually obtained through the EPS recording system), a pulse oximeter, a non-invasive blood pressure measurement cuff, and external defibrillation pads.

Of note, the administration of intravenous sedation should be generally avoided since it can impede the induction of arrhythmias. Nevertheless, light sedation with the combination of benzodiazepines, opiates, and antiemetics is given in the great majority of patients to relieve pain from the initial puncture and anxiety.[7]

Technique or Treatment

The interpretation of an electrophysiological study includes the assessment of both the morphology and the timing of EGMs at baseline and after programmed electrical stimulation of the heart in relation to two or more simultaneously recorded surface ECG signals. Of note, the recording speed commonly used in EPS is 100 to 200 mm/sec instead of the usual 25 mm/sec of normal ECG recording. This sweep speed is adequate for a clear display of EGMs as well as for accurate measurements of the time intervals among the various deflections. While atrial and ventricular signals are easy to obtain and recognize due to their simultaneous inscription with the surface P and QRS complexes, the His bundle EGM requires specific maneuvers of the recording catheter, which must be oriented septally at the level of the tricuspid ring. In this area, His bundle EGM can be recorded as a biphasic or triphasic sharp deflection interpolated between the atrial and ventricular signals. Another important point is the recordings obtained from the multipolar CS catheter. Since CS runs in the atrioventricular groove, the electrophysiology catheter records both atrial and ventricular signals. More importantly, the signals obtained from the distal (near the tip located) pairs of electrodes originate from the left atrium and the left ventricle, while those inscribed from the more proximal pairs of electrodes are coming for the right side. This way, the CS recording makes possible the distinction between right and left atrial signals.

Beyond the identification of EGMs, the interpretation of an EPS requires the understanding of the following terms:

- Cycle Length (CL): It is measured between two consecutive events in milliseconds (ms) i.e., between two consecutive normal or paced atrial or ventricular signals. The shorter the cycle length, the faster the rate. For instance, the cycle length of 600 ms corresponds to a heart rate of 100 beats/min, while a cycle length of 400 ms corresponds to a heart rate of 150 beats/min.

- Programmed Stimulation: The pacing of cardiac tissue through one electrophysiology catheter.

- Incremental pacing (or burst pacing): The introduction of a specific number of pacing stimuli (train) at a progressive shorter cycle length.

- Extra stimulus pacing: Introduction of one or more (more commonly up to three) premature impulses at specific coupling intervals. The extra stimuli are introduced after a native impulse or after a train of eight impulses paced at a fixed cycle.

- Coupling Interval: The time measured in ms between a normal impulse and a premature impulse introduced through programmed stimulation (pacing).

- Effective Refractory Period (ERP): Refers to a particular tissue or structure; for example, ERP of the ventricle or the atrioventricular (AV) node. It is the longest coupling interval at which a premature impulse fails to propagate through the tissue or the structure.

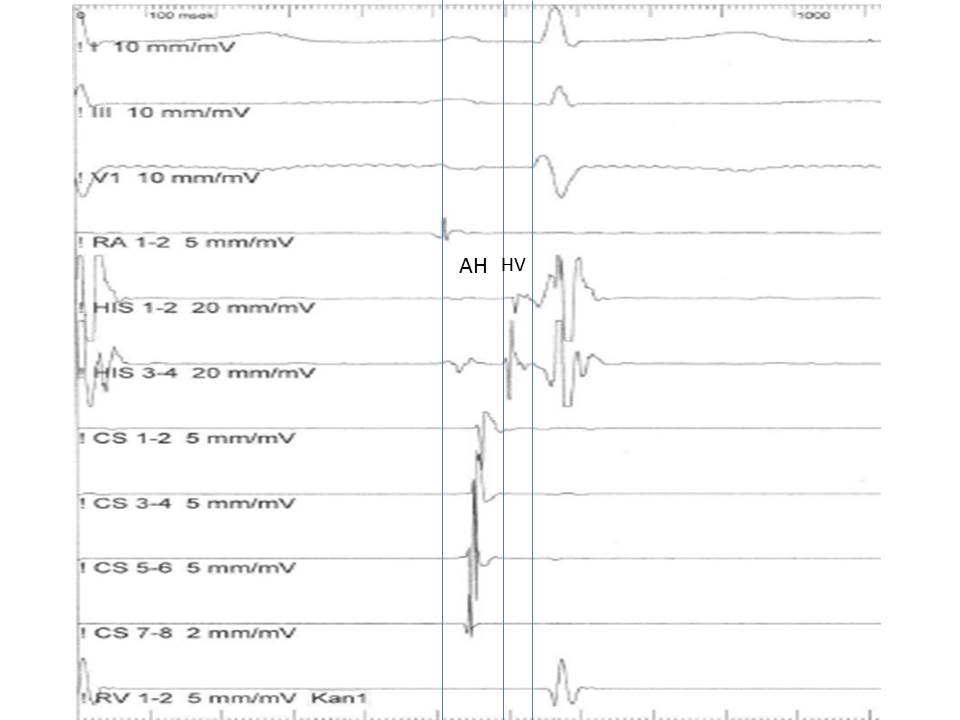

The baseline analysis of intracardiac recordings starts with the measurement of the time intervals between consecutive signals in relation to the normal activation sequence of the heart in sinus rhythm. Since the sinus node is located high in the right atrium, the first atrial bipolar EGM is recorded form the HRA catheter, followed by the atrial signals in the His catheter and the proximal poles of the CS catheter. The most delayed atrial signal is normally inscribed from the distal pole of the CS catheter (CS 1,2), which is located at the lateral wall of the left atrium. The atrial signals are followed from the His signal and after that from the RV signal. The baseline time intervals (conduction intervals) measured after the identification of EGMs are:

PA Interval: Measured from the onset of the P wave to the onset of the low atrial signal in the His bundle recording. Represents the intra-atrial conduction time (normally: 25 to 55 ms).

AH Interval: Measured from the onset of the atrial signal to the onset of His bundle signal in His catheter recording. Represents the conduction time through the AV node (normally 55 to 125 msec).

H Time: Measured from the onset to the end of His bundle recording. Represents the conduction time through the His bundle (normally < 30 ms).

HV Interval: Measured from the onset of His deflection to the onset of the QRS in the surface EKG. Represents the conduction time from the His bundle to the ventricular myocardium (normally 35nto 55 msec). (Figure 3)

Clinical Significance

Concerning the clinical significance of the procedure, the evaluation of sinus node dysfunction, atrioventricular conduction abnormalities, supraventricular or ventricular tachyarrhythmias as well as electrophysiologic findings after successful ablation of an arrhythmia, must be addressed.

Evaluation of Sinus Node Dysfunction

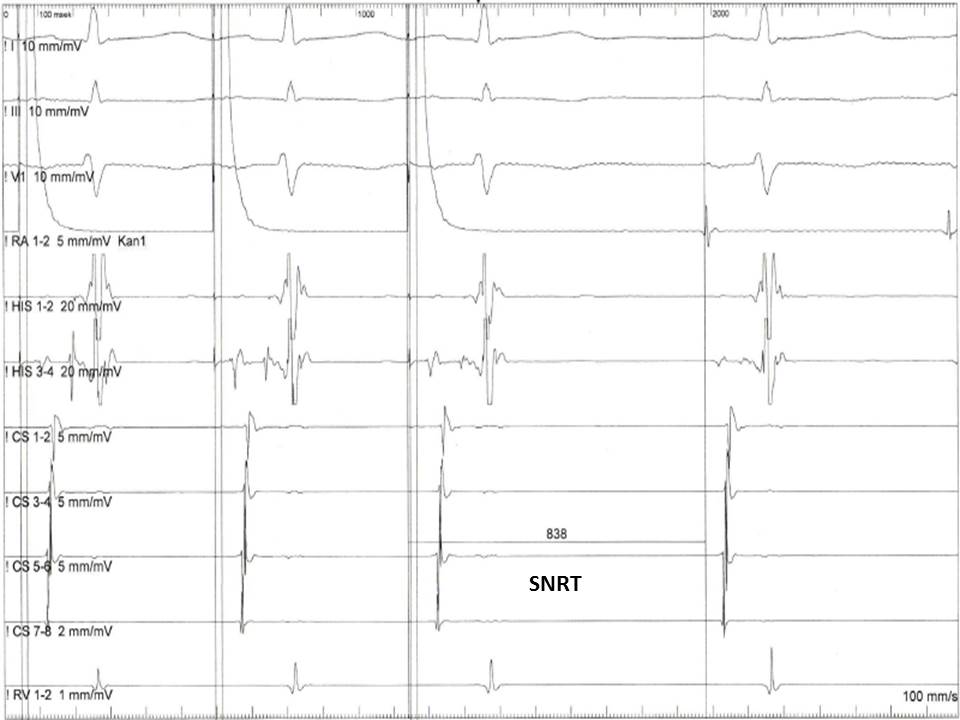

The electrophysiologic evaluation of sinus node dysfunction includes the measurement of the sinus node recovery time (SNRT) and of the sino-atrial conduction time (SACT). The SNRT is the most important of these two parameters and is defined as the time interval between the last paced atrial signal to the first spontaneous atrial electrogram in the HRA recording (Figure 4). The protocol includes the stimulation of the atria at a fixed rate for 30 seconds at various CLs (600, 500, and 400 ms). The stimulation is then abruptly terminated, and the time needed for the sinus node to regain its automaticity is measured. Normally the SNRT must be less than 1600 ms. To standardize the measurement, the sinus CL is usually subtracted from the SNRT. The corrected SNRT (cSNRT) should be no longer than 525 ms.

The SACT is rarely measured nowadays in clinical practice. It is an estimate of the time needed from the sinus impulse to reach the perinodal atrial tissue. A prolonged SACT indicates some degree of sinus exit block. It is measured after the delivery of premature atrial stimuli (Strauss method) or after continuous atrial pacing at a rate slightly faster than the basic sinus cycle. The impulse is always delivered from the HRA catheter, which is located near the sinus node. Similarly to the SNRT measurement, the time from the last paced atrial signal to the first spontaneous sinus signal is measured. This return interval represents the sum of time the paced impulse needs to conduct from the HRA into the sinus node, plus the time that is needed for the subsequent spontaneous sinus node beat to conduct through the peri-nodal tissue, plus the spontaneous sinus cycle length. Assuming that the conduction times in and out of the sinus node, i.e., the SACT, are equal, then the SACT can be calculated from the formula:

Return Interval = Spontaneous cycle length + 2 x SACT

It should be noted that the role of electrophysiologic evaluation of sinus node dysfunction had substantially subsided in recent years. The various non-invasive monitoring methods have shown a better diagnostic yield. Nevertheless, the method can still be useful for the assessment of patients with syncope and asymptomatic bradycardia or sinoatrial block documented in surface ECG.[10]

Evaluation of Atrioventricular Conduction Abnormalities

His bundle recording is the focus of interest for the assessment of atrioventricular conduction abnormalities. A prolongation of the AV interval in the His EGM denotes a block within the compact AV node, which usually does not need any further evaluation or treatment. On the other hand, longer duration or splitting of the His EGM in two components reflects a conduction delay within the His bundle, while a significant prolongation of the HV time (more than 100 ms) indicates a block below the AV node in the His-Purkinje system.[11] Both these abnormalities are an indication for implantation of a permanent pacemaker since they can suddenly progress to a complete AV block, causing syncope and even sudden cardiac death.

If the patient presents with symptoms suggesting an atrioventricular conduction abnormality but the baseline intervals in the His EGM are within normal limits, a further assessment of the AV conduction system under "stress" is required. This is accomplished through the delivery of extra atrial stimuli at progressively shorter intervals or through incremental atrial pacing. A gradual prolongation of the AH interval at progressively earlier premature extra atrial stimuli or progressively faster atrial pacing rates is a normal response of the AV node called "decremental conduction." This normal conduction delay of the incoming impulses at the level of the AV node is a protective mechanism against the development of rapid and potentially dangerous ventricular rates. The goal of the pacing protocols is to determine when an AV block occurs and if it occurs at the level of the AV node (supra-His block) or the level of His Purkinje system (infra-His block). In the first case, an atrial signal without following His and ventricular signals will be recorded in His bundle EGM. On the contrary, an atrial signal followed by a His deflection in the absence of a subsequent ventricular signal indicates a block distal to the AV node and establishes the indication of pacemaker implantation.[12]

Evaluation of Supraventricular Tachyarrhythmias

The assessment of supraventricular tachyarrhythmias is the most challenging but also the most important part of an electrophysiological study since it offers invaluable information about the mechanism of the arrhythmia and guides the therapy. Abnormal automaticity and reentry are the two main electrophysiologic abnormalities causing tachyarrhythmias.

Abnormal automaticity refers to the abnormal initiation of an impulse from one myocardial focus (cell or group of cells) different from the sinus node. The focal tachyarrhythmias are characterized by a rate acceleration at the beginning and a rate deceleration at the end of the arrhythmia, the so-called "warm-up" and "cool down" phenomenon. Focal atria tachycardia (FAT) is the most common supraventricular tachyarrhythmia due to abnormal automaticity.[13]

On the other hand, the reentry mechanism is not associated with the initiation but with the propagation of the impulse. A non-uniformly propagated impulse results in late activation of myocardial regions (conduction delay) while other previously excited regions have recovered excitability and, as a consequence, can be re-excited retrogradely from the same impulse. This electrophysiologic abnormality can lead to the establishment of a continuous circuit, while the propagation of the rapid circulating impulse to the rest of the myocardium results in a tachyarrhythmia with an abrupt onset. More importantly, any type of block (e.g., pharmaceutical or invasive) at any limb of the reentry circuit can abruptly terminate the arrhythmia. The most common reentrant supraventricular tachyarrhythmias are the atrioventricular nodal reentrant tachycardia (AVNRT), the orthodromic and antidromic atrioventricular reentrant tachycardias (AVRT) and the macro-reentry atrial tachycardias (MRAT). In AVNRT, the most common reentrant arrhythmia, the reentrant circuit is located within the AV node. It is usually composed of two pathways, a fast (faster conduction and longer refractory period) and a slow pathway (slower conduction and shorter refractory period).

On the other hand, in AVRT, the AV conduction system is one of the two limbs of the reentrant circuit, with the other being an accessory pathway conducting either retrograde from the ventricles to the atria (orthodromic AVRT) or anterograde from the atria to the ventricles (antidromic AVNRT). Finally, in MRAT, the AV conduction system is not part of the reentry circuit, which is confined within the atrial tissue. They are further divided into cavotricuspid isthmus-dependent when the circuit passes through the anatomical area confined by the inferior vena cava and the tricuspid ring (i.e., common and reverse atrial flutter) and non-cavotricuspid isthmus-dependent or atypical flutter if the circuit is located somewhere else in the right or the left atrium.

EPS aims to make; initially, an appropriate differential diagnosis of a spontaneously running or induced supraventricular arrhythmia (through programmed atrial or ventricular stimulation).[14] Beyond the observation of the specific EGM pattern of the arrhythmia, additional pacing maneuvers may be needed to establish the diagnosis. After the diagnosis has been confirmed, therapeutic intervention with the application of radiofrequency energy through specifically designed ablation catheters in critical areas within the heart usually follows. Finally, a control EPS is performed 30-60 minutes after the ablation procedure to evaluate the effectiveness of the therapy.

The observation of EGMs recorded in sinus rhythm can offer important initial information about the mechanism of arrhythmia. The presence of an accessory pathway makes the diagnosis of AVRT highly likely. An overt pre-excitation in the ECG leads together with the fusion of the A and V signals, and the negative HV interval (meaning that the beginning of the QRS precedes the His signal) establishes the diagnosis of an accessory pathway. On the other hand, the absence of retrograde conduction during ventricular pacing in sinus rhythm rules out a retrograde conducting accessory pathway and accordingly excludes the diagnosis of AVRT.

The initiation of the tachycardia is the first point that needs to be addressed during the EPS. All SVTs can be induced with atrial stimulation, while ventricular stimulation can induce easily an AVRT, less commonly an AVNRT, and very rarely a FAT or an MRAT. Moreover, a reentry tachycardia is induced more easily when an extra stimulus is delivered at the right moment (extra stimulus pacing), while the induction of a focal tachycardia is facilitated mainly from incremental pacing. Also, a significant conduction delay of the last beat before the onset of the tachycardia is a strong indication of a reentry mechanism, since it implies a shift of the impulse propagation from the fast conducting limb to the slow one. At the level of the AV node, a gradual increase in the AH interval with progressively shorter coupling intervals of the extra atrial stimuli is normally expected due to the decremental conduction property of the AV. A sudden increase ("jump") in the AH interval of at least 50 ms, though, indicates that the ERP of the fast pathway is reached, and the impulse is conducted through the slow pathway. If the excitability of the fast pathway has recovered at the time the impulse reaches the end of the slow pathway, retrograde conduction ("echo beat ") through the fast pathway can happen (Figure 5).

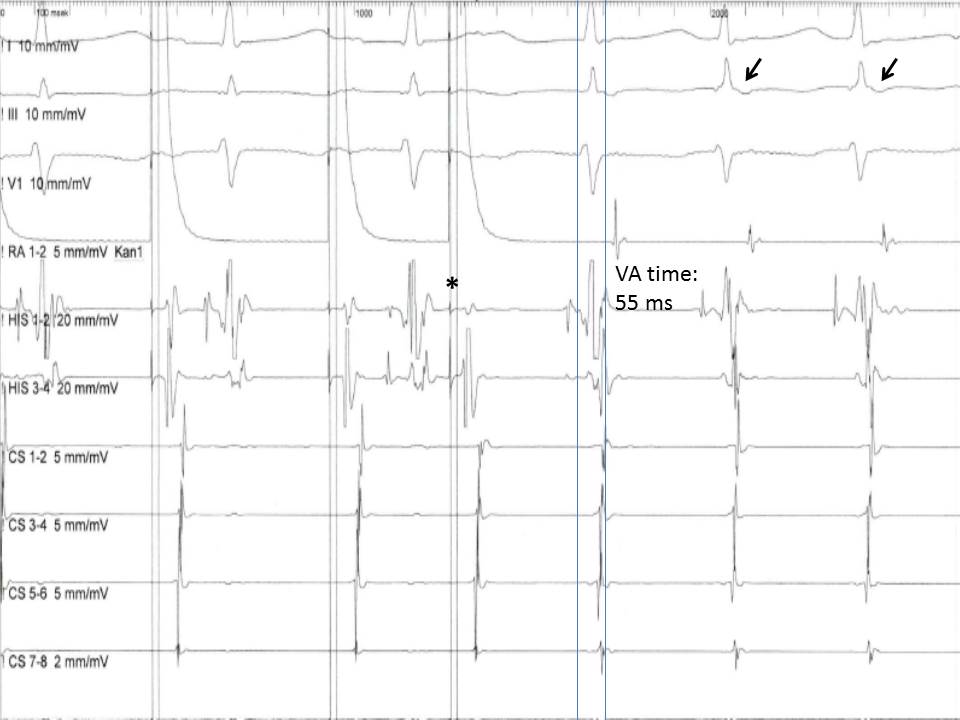

Almost simultaneous activation of the atria and the ventricles is recorded with a ventriculoatrial (VA) interval, measured for the earliest QRS deflection to the earliest atrial deflection in the His bundle EGM, typically less than 60 ms.[15] This pattern of anterograde and retrograde conduction can be interrupted after the first "echo beat" if there is a change in the refractoriness of the two limbs of the reentry circuit or can continue as AVNRT. On the other hand, if the limbs of the reentrant circuit include the AV node-His-Purkinje system and an accessory pathway, a VA interval is expected to be more than 65 ms in the case of an orthodromic AVRT, since the retrograde conduction of the impulse through the ventricular tissue and the accessory pathway back to atria requires more time.

The mode of termination of the arrhythmia can also help delineate its mechanism. If the tachycardia terminates with an atrial EGM, i.e., with AV block, the diagnosis of FAT is unlikely since there is no reason for the last atrial impulse initiated from the ectopic focus not to be conducted to the ventricles. On the other hand, any type of supraventricular tachycardia can terminate with a ventricular EGM, a pattern which does not provide any diagnostic information regarding the mechanism of the arrhythmia.

The pattern of atrial activation during the tachycardia is another important diagnostic feature of the EPS. In MRATs, for example, atrial signals are recorded throughout the cycle length of the tachycardia while in the other types of supraventricular tachycardia atrial EGMs take up only a small portion of the tachycardia cycle. Moreover, the earliest atrial EGM can indicate the site of origin of the arrhythmia. If the earliest signal is recorded in the high right atrium, a right-sided FAT or an AVRT through a right-sided accessory pathway are the most likely diagnoses. On the contrary, an earliest atrial activation signal recorded in the distal poles of the CS catheter ("eccentric activation pattern") indicates an AVRT with retrograde atrial activation through a left-sided accessory pathway or a left FAT.

Finally, the response of the tachycardia to atrial and ventricular stimulation provides further clues for the diagnosis. An atrial extra stimulus, for example, can penetrate a reentrant circuit, collide with the circulating impulse and terminate the arrhythmia. Such a response is less likely if a focal activity is the mechanism of arrhythmia. Ventricular stimulation, on the other hand, is even more informative of the mechanism of arrhythmia. A ventricular extra stimulus appropriately timed can penetrate the atria through the His bundle and reset the tachycardia changing its cycle length. If that happens when the His bundle is in the refractory phase and does not permit conduction through it (His synchronous pacing), then an alternative route must be responsible for the retrograde atrial conduction. This finding establishes the diagnosis of an accessory pathway, which is most likely part of the reentry circuit. Moreover, if this maneuver, instead of resetting, terminates the tachycardia without conduction of the extra stimulus to the atrium, then AVRT is ruled out, and the accessory pathway is a necessary part of the arrhythmia and not a possible bystander. On the other hand, this finding does not rule out an AVNRT. The reason is that even in the case of AV dissociation, which typically happens when a ventricular beat is not conducted back to the atria, AVNRT can still go on since the reentrant circuit is defined in the AV node and His Purkinje system is not a part of it.

Beyond the resetting with a single ventricular extra stimulus, a continuous resetting of the tachycardia through ventricular pacing at a rate slightly faster than the cycle length of the arrhythmia (overdrive pacing) can also happen. Penetration of the paced beats through an accessory pathway or the AV node can reset and accelerate (entrain) the tachycardia at the paced cycle length. Of importance is the recording immediately after the cessation of pacing. In the case of a reentry tachycardia, the last paced beat is conducted up to the atrium through one of the limbs of the reentrant circuit (AV node or accessory pathway) and travels back to the ventricles through the other limb of the loop continuing the tachycardia (as so-called VAVA response). On the other hand, in the case of a FAT, the paced ventricular pulse is conducted retrograde through the AV node and suppresses the ectopic focus through the premature atrial depolarization. This premature atrial impulse cannot be conducted back to the ventricles because the AV node is still refractory from its previous retrograde depolarization. For the tachycardia to continue, a new A wave has to be generated and travel down to the ventricles (a so-called VAAV response).

Evaluation of Ventricular Tachyarrhythmias

Similarly to the supraventricular tachycardias, abnormal automaticity and reentry are the two main mechanisms of ventricular arrhythmias. Premature ventricular contractions (PVC) are always of focal origin. On the other hand, ventricular tachycardia (VT) can be either focal or reentrant. The role of baseline electrophysiologic evaluation is rather limited in the case of ventricular arrhythmias. It is practically confined to the confirmation of the diagnosis of VT and the induction of VT through various stimulation protocols. Of note, the inducibility of a VT with ventricular extra stimuli is highly suggestive of a reentry mechanism.

AV dissociation, the hallmark of VT, is easy to recognize from the simultaneous recording of atrial and ventricular EGMs. Nevertheless, VT with 1:1 VA conduction can also happen. In that case, the diagnosis of VT is more difficult since an SVT with aberrancy (conduction of atrial signals to the ventricles with bundle branch block or through an accessory pathway) cannot be excluded. The induction of AV block with the administration of adenosine is the easiest way to dissociate the atria transiently from the ventricles. If the wide complex tachycardia continues, then VT is the most likely diagnosis.

The induction of VT with extra stimulus ventricular pacing is highly suggestive of reentry as the underlying mechanism. However, the induction of a VT is not as easy as it is in the case of reentrant SVTs. One important reason is the distance between the pacing site, usually at the apex of the right ventricle, and the reentrant circuit usually located in the epicardium or the sub-endocardium in the left ventricle. To facilitate the penetration of the premature stimulus in the reentrant circuit, a 'drive train' of 8 paced beats are followed by 1 to 3 premature stimuli. The idea is to shorten the refractory period with the fast pacing increasing this way the chances of the extra stimuli to reach and penetrate the reentrant circuit. Most of the pacing protocols use a drive CL of 600, 500, and 400 msec. The extra stimuli are then delivered at progressively shortened coupling intervals up to the point of refractoriness (no capture) of the ventricular myocardium.[16] The induction of a sustained monomorphic VT is a clear indication for the implantation of a cardioverter-defibrillator. In contrast, the induction of ventricular fibrillation is considered a non-specific response without clinical significance and is usually the result of an aggressive pacing protocol.[17]

Electrophysiologic Findings After Successful Ablation of an Arrhythmia

A controlled electrophysiological study is always performed after an ablation procedure to assess the immediate result and to predict the long-term outcome. Non-inducibility of the ablated arrhythmia after programmed stimulation is the main finding indicating a successful endpoint. More specific findings include:

- After the ablation of an AVNRT: Loss of the AV jump, which indicates the complete elimination of the 'slow pathway' or presence of the AV jump but induction of no more than one echo beats, which indicates an effective AV modification.[18]

- After the ablation of an accessory pathway: Disappearance of the delta wave in ECG along with the abolishment of the continuity between the atrial and ventricular signals.[19]

- After the ablation of macro-reentry tachycardia: The significant prolongation of conduction time from one to the other side of the ablation line or the recording of double potentials along this line. These findings indicate a successful conduction block of the macro-reentry circuit in this particular anatomic area.[20]