Continuing Education Activity

Steppage gait is an entity that is not too commonly seen in primary care settings. The etiology of this disorder is multifactorial. The pathology and location of the lesions are quite complex, spanning the entire neuraxis from upper motor neurons to the peripheral nerve. This activity illustrates the evaluation and management of foot drop and highlights the role of the interprofessional team in evaluating and treating care for patients with this condition. Upon completion, the readers will understand the etiology, pathology, and diagnosis of a person presenting with a steppage gait. Diagnostic and management options, including an interprofessional approach, are discussed.

Objectives:

- Describe risk factors for developing steppage gait.

- Review the history and physical examination findings associated with steppage gait.

- Summarize the treatment and management options available for steppage gait.

- Outline interprofessional team strategies for improving care, coordination, and communication to advance treatment for patients with steppage gait and improve outcomes.

Introduction

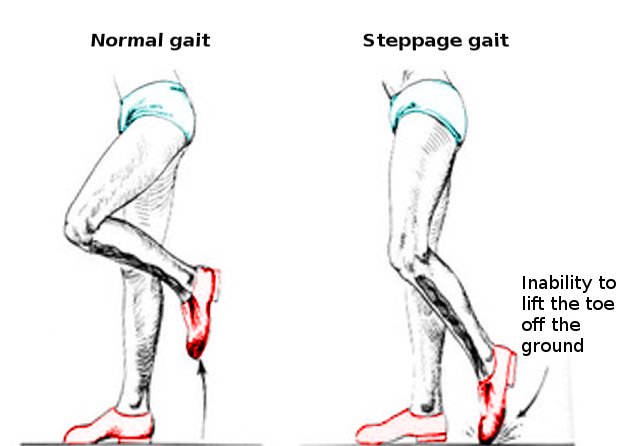

Steppage gait is the inability to lift the foot while walking due to the weakness of muscles that cause dorsiflexion of the ankle joint. Foot drop is not a commonly seen condition. The typical presentation is one of a patient who presents with a sudden onset of weakness of the muscles that extend the foot during walking. The history usually consists of unusual activity, a surgical procedure, prolonged bed rest, an accident leading to fracture, or a tight cast applied to the lower extremity. The other possibilities include a history of collagen vascular diseases leading to nerve ischemia. Peripheral neuropathies, the most common cause being diabetes, can lead to unilateral or bilateral foot drop. Upper motor neuron lesions can also present as foot drop. However, the presentation also includes hemiplegia and aphasia.

Etiology

Any damage or compression of the neuraxis anywhere along this pathway can potentially lead to foot drop and steppage gait. Frequent reasons include traumatic injuries, pelvic fractures, tibia or fibular head fractures, tight casts, prolonged positioning in lithotomy during surgical procedures, compression by a space-occupying lesion, vascular impairments as in conditions as lupus, or Waldenstrom macroglobulinemia which can lead to vasculitis causing nerve ischemia. Neuropathies affecting the nerves of the peripheral nervous system are referred to as peripheral neuropathies. These can be primarily demyelinating, primarily axonal, or mixed. Primary demyelinating neuropathies can be acquired or congenital. Examples of acquired neuropathies include acquired inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy (AIDP) and chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy (CIDP). Hereditary neuropathies include Charcot-Marie Tooth (CMT), and hereditary preponderance to pressure palsies (HNPP). GNE (UDP-N-acetylglucosamine 2-epimerase/N-acetylmannosamine kinase) myopathy (Nonaka myopathy), GARS1 (Glycyl-TRNA Synthetase 1)-associated axonal neuropathy, and alkaptonuria are rare causes.[1][2]

Predominantly axonal neuropathies are seen with exposure to toxins, viral or bacterial infections, chemotherapeutic agents as vincristine or vinblastin.

Diabetes, alcohol intoxication, and renal disease can lead to mixed peripheral polyneuropathies.

The primary causes of foot drop include cerebral vascular accident (CVA) and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. CVA presents as hemiparesis or hemiplegia, associated with dysphagia, dysarthria, or aphasia.[3][4]

Foot drop with a high steppage gait ("cock-walk gait") is of the upper motor neuron type.

Epidemiology

Peroneal neuropathy is more common in males (male-to-female ratio, 2.8 to 1). Approximately 90% of peroneal lesions are unilateral, with no preference for the side.

- The frequency of occurrence is 0.3 to 4% after total knee arthroplasty (TKA).

- 3 to 13% of cases may end up with foot drop after proximal tibial osteotomy.

Pathophysiology

- To understand the pathophysiology and prognosis, knowledge of nerve injury classification is necessary. In 1943 Seddon and 1953 Sunderland have proposed a classification that is still in use. Accordingly, there are three degrees 1) neurapraxia, 2) axonotmesis, and 3) neurotmesis.

- In neurapraxia, the nerve remains intact, but due to a temporary injury to myelin, the propagation of the signal is affected. The endoneurium, perineurium, and the epineurium remain intact. Conduction is unaffected in the distal segment and proximal segment, but no conduction occurs across the area of injury; the term for this is conduction block. Conduction studies reveal signs of demyelination as prolonged latency and slow nerve conduction velocity across the compressed segment. The prognosis for recovery is the best of the three classifications.

- In axonotmesis, the axon becomes damaged, but the surrounding connecting tissue, i.e., the epineurium and perineurium, remain intact. Wallerian degeneration takes place distal to the site of injury. Nerve conduction studies show sensory and motor deficits distal to the site of the lesion. Some conduction that may initially be present disappears after 3 to 4 days following the injury. In 3 to 4 weeks after the injury, signs of axonal damage, i.e., fibrillation potentials (FP), and positive sharp waves appear. Eventually, axonal regeneration occurs, and recovery is possible, although it may not always be complete.

- The last degree is neurotmesis, in which both the axon and connective tissue suffer damage. Wallerian degeneration occurs distally to the injury site. Sensory-motor problems and autonomic function defects accompany this. Nerve conduction distal to the injury site is not possible. Since electromyography (EMG) and nerve conduction velocity (NCV) findings are similar to those of the second degree, the distinction is difficult. Surgical intervention is sometimes necessary.[5][6]

- There are five lumbar vertebrae. From each of the five lumbar vertebrae nerves, roots emerge. They extend from L1 to S4. These nerve roots emerge from the lateral spinal recess formed by the superior facet of the distal vertebra and the inferior facet of the proximal vertebra. They join to form the lumbosacral plexus. The lumbosacral plexus has only two main components: the portion made of nerve fibers from the L2 through L5 roots is called lumbar plexus, and the other from S1 through S4 roots is called sacral plexus.

- Anteriorly, the largest branch that emerges from the LS plexus is the femoral nerve. Posteriorly, another large branch emerges through the sciatic notch and is called the sciatic nerve. At or around the popliteal fossa, this nerve divides into two branches — the tibial and fibular or peroneal nerve. The tibial nerve travels down to the posterior thigh supplying the hamstring group, then continues to supply the calf muscles, the gastric soleus tibialis posterior, flexor hallucis, and flexor digitorum and all the intrinsic muscles of the foot.

- The sural nerve is a large sensory nerve that gets contributions from both the tibial and peroneal nerves; this is the primary sensory nerve that supplies the posterior leg and heel.

- The common peroneal nerve continues down the lateral side of the leg at the fibular head. It divides into the superficial peroneal nerve, which supplies the peroneus longus and brevis, the main eversion muscles of the foot.

- The superficial branch supplies sensation to the dorsum of the foot and lateral calf. The deep branch supplies a small area at the first webspace.[7] The deep peroneal nerve innervates the dorsiflexors, i.e., tibialis anterior, extensor digitorum longus and brevis, and extensor hallucis longus muscles. These are responsible for ankle dorsiflexion.

- Because of its superficial location, the peroneal nerve is vulnerable to compression during surgical procedures, tight cast placements, and other traumatic conditions sustained during sports. Patients with diabetes seem to be affected more often. Any compression of the common peroneal nerve leads to foot drop.

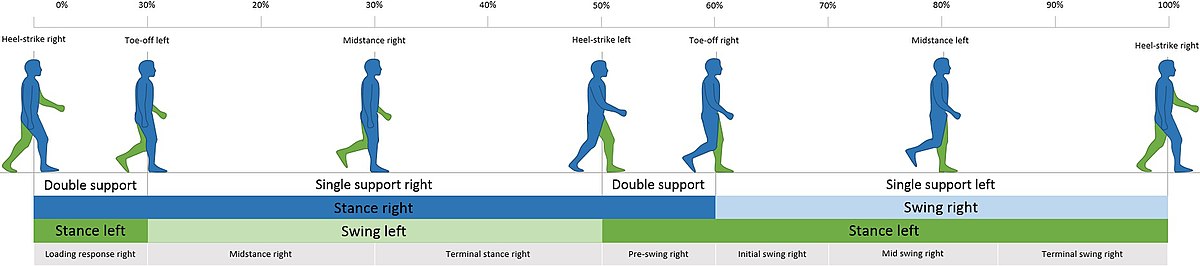

- The normal gait cycle consists of the stance phase of 60% and the swing phase of 40%. When one foot is in the swing phase, the other is in the stance phase. The gait cycle starts with a heel strike and ends with a heel strike on the same side. During the stance phase, the foot remains flat on the ground. In the heel strike, the foot is in dorsiflexion, preparing for gradual lowering before the stance phase. Any damage affecting the neuraxis from the roots to the peripheral nerve can lead to weakness of the muscles supplied by that nerve. Therefore a lesion of the L5 root, lumbar plexus, sciatic nerve, common peroneal, or the deep peroneal nerve can potentially lead to foot drop due to the weakness of the anterior compartment musculature. The presenting symptom is the inability to ambulate as before. More specifically, there is a weakness of the muscles in the foot that assist in dorsiflexion. There may or may not be a pain. The person will be unable to dorsiflex during the heel strike, and the foot remains flat on the ground. Sometimes this can also cause toe drag and inability to clear the foot, potentially leading to falls.

History and Physical

The most common presenting complaint is the inability to ambulate as before, due to the weakness of the muscles responsible for maintaining the foot in dorsiflexion during heel strike, which can lead to falls. History is usually positive for either a cerebrovascular accident (CVA), collagen vascular diseases, surgery, fracture of tibia or fibula, or prolonged stupor state and protracted bed rest as in the ICU.

Physical examination reveals the weakness of the anterior compartment muscles of the leg. Sensory loss involves the anterior aspect of the foot. Reflexes may be brisk, with upgoing plantar reflex in CVA cases or absent in lower motor neuron (LMN) disorders.

Evaluation

Diagnostic testing should include plain X-rays of the pelvis and tibia/fibula to rule out fracture or dislocation in case of trauma. Suspected plexopathies may indicate magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).

- In the case of collagen vascular diseases, rheumatoid factor, antinuclear antibody (ANA), and other relevant labs should be checked. Complete blood count, differential count, and SMA 18 to rule out sepsis merit consideration.

- Electromyography (EMG) and Nerve Conduction Velocity (NCV) studies - Findings will include denervation potentials and motor units.[8] L5 radiculopathy, lumbar plexopathy, and a lumbosacral trunk lesion will all produce weakness of tibialis posterior, which gets spared in peroneal neuropathy. The lateral trunk of the sciatic nerve involvement can be differentiated from peroneal neuropathy by the weakness of the short head of biceps in the former. These two muscles are testable by EMG.[9]

- In mild cases, referral to physical therapy for pain reduction and strengthening exercises to the weak muscles coupled with a range of motion (ROM) to the ankle to prevent contractures is beneficial.

- If EMG shows complete loss of continuity along with evidence of neurotmesis or axonotmesis, an ankle-foot orthosis (AFO) is indicated. The purpose of the brace is to maintain the foot in neutral during the toe-off phase of the gait cycle. Periodic skin checks are advisable since the anesthetic foot can develop pressure ulcers at the contact points with the brace. A shoe wide enough to accommodate the brace is necessary.[8]

Treatment / Management

Mild cases warrant a referral to physical therapy for pain reduction and strengthening exercises to the weak muscles coupled with a range of motion (ROM) to the ankle to prevent contractures. If EMG shows complete loss of neural continuity along with evidence of neurotmesis or axonotmesis, an ankle-foot orthosis (AFO) is indicated. The purpose of the brace is to maintain the foot in neutral during the toe-off phase of the gait cycle. Periodic skin checks are necessary since the anesthetic foot can develop pressure ulcers at the contact points with the brace. A shoe wide enough to accommodate the brace is necessary.

Tibialis posterior tendon transfer or peroneal or tibial nerve transfer can be useful for patients with foot drop leading to high steppage gait.[10][11]

A home exercise program should be an integral part of therapy.[12]

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis of this condition is quite broad and encompasses a wide range of neuromuscular disorders from the cerebral cortex to the peripheral nerve.

- Central causes such as a CVA or multiple sclerosis (MS), myelopathies, either cervical or thoracic regions, can also cause foot weakness. However, the patient will have other associated symptoms and signs of upper motor neuron involvement as hyperactive reflexes, increased tone, bladder, and bowel symptoms.

- Lumbar radiculopathy due to disc herniation or spinal stenosis

- Lumbar plexopathies

- Sciatic neuropathy

Other types of gait which require differentiation from steppage gait are:

- Circumduction gait (upper motor neuron involvement in CVA) - can cause weakness of the whole extremity. The patient ambulates with a circumduction gait since the limb is artificially long due to paralysis. To clear the ground, the person would have to circumduct. Other signs of CVA as dysphagia, or aphasia and upper limb weakness, are also evident.

- Cerebellar gait - involvement of the cerebellum leads to balance deficits causing the inability to walk in tandem.[13]

- Ataxic gait - presentation is bilateral. The person will not be able to walk normally. There is a lack of proprioception and position sense due to the involvement of long tracts of the spinal cord, leading to a gait that is remarkable for high steppage and side-to-side sway, as can be seen in persons who misuse alcohol.

- Parkinsonian gait - Due to the involvement of substantia nigra, there is a lack of initiation leading to festinating gait. The smooth transition of the gait cycle phases is disturbed.

- Complications mostly relate to the inability to clear the ground during walking, which leads to falls. The ill-fitting brace can potentially cause skin abrasions by rubbing against anesthetized skin. Parts of braces can eventually become loose due to wear and tear

Prognosis

EMG and NCV studies are beneficial to diagnose the nature, location of compression, and prognosis. If the test shows delayed latency and slow velocity, as well as conduction block at the involved segment with no evidence of denervation potentials and plenty of motor units on needle EMG, it indicates neurapraxia with a good prognosis. Conversely, if there is evidence of denervation potentials coupled with no viable motor units, the prognosis is guarded.[14]

Complications

Complications mostly relate to the inability to clear the ground during walking, which leads to falls. The ill-fitting brace can potentially cause skin abrasions by rubbing against anesthetized skin. Parts of braces can eventually become loose due to wear and tear.

Postoperative and Rehabilitation Care

A consultation with physical medicine & rehabilitation (PM&R) specialist is necessary. A physiatrist will perform an evaluation, electrodiagnostic studies, and brace management.

Physiotherapy referrals are usually taken care of by the physiatrists.

They also can refer the patient to an orthotist for a brace.

Consultations

The patients should obtain the following consultations should be obtained:

- PM&R

- Physical therapy

- Orthotist

- EMG by neurology or PM&R

Deterrence and Patient Education

The patient is an integral part of the team. They should be included in the diagnosis and other decision-making processes, including management options. Education regarding exercises, home exercise programs, skincare, and brace maintenance will result in better outcomes.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

A patient with foot drop may present with weakness of the anterior muscles in the leg, which may be due to central or peripheral causes. A careful history and physical examination are an integral part of the assessment. The nurse practitioner or a primary care specialist needs to refer to a neurologist and/or a PM&R specialist. Coordination with a physical therapist and an orthotist plays a significant role in better recovery and improved outcomes. These patients need to be followed for a long time, as recovery is rarely immediate. In fact, some patients may need to wear an orthotic appliance for life. A nurse with specialized orthopedic training is also a useful member of the team, monitoring the patient, serving as a bridge with the treating clinician, as well as counseling the patient. All these members of the interprofessional health care team have a role to play in managing foot drop patients to achieve an optimal benefit to the patient. [Level 5]