Introduction

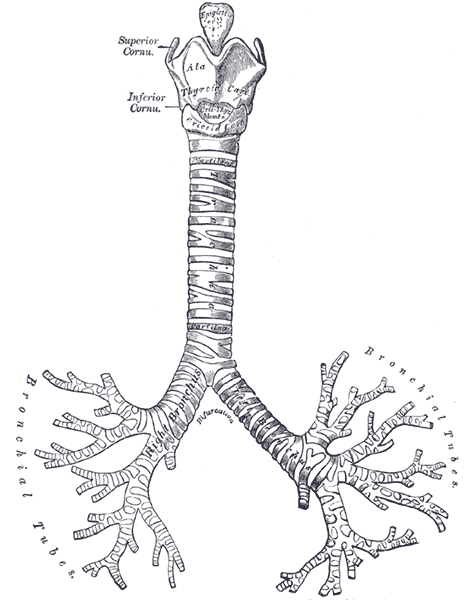

The trachea is a U-shaped structure that is composed of hyaline cartilage on the anterior and lateral walls, with the trachealis smooth muscle forming the posterior border of the trachea. The entire tracheal lumen is lined by ciliated pseudostratified columnar and goblet cells that create the tracheal mucosa. The trachea is part of the conducting airway system that begins immediately inferior to the larynx connected to the cricothyroid cartilage (C6 level) by the cricotracheal ligament. Followed by a series of 16 to 20 hyaline cartilage rings each is individually connected by an annular ligament and terminates at the carina (T5 level posteriorly| sternal angle anteriorly). It then splits into the right and left main bronchi.[1][2][3]

Structure and Function

The tracheal mucosa is composed of ciliated pseudostratified columnar and goblet cells. Goblet cells produce mucus that contains immunoglobulin A (IgA), lysozymes, lactoferrin, and peroxidases. The mucous entrains and traps air debris (2 micrometers to 10 micrometers) which is expelled from the airway through the upward movement of the cilli.

That trachealis muscle also aids in expectoration with contraction against a closed epiglottis with a sudden opening resulting in great force to expel the substance.

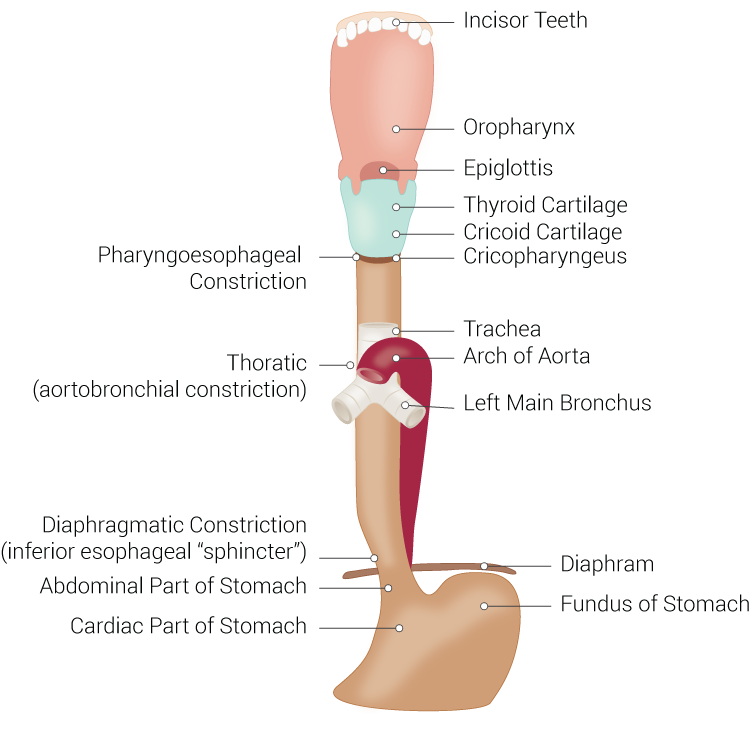

The trachea is a conducting airway and is essential for the passage of oxygen and other gasses to travel to the alveoli for diffusion. The pathway is as follows: the mouth or nare, the oral cavity or nasal cavity, oral pharynx or upper pharynx, pharynx, larynx, trachea, bronchi, bronchioles, terminal bronchioles, alveolar ducts, alveolar sacks, and lastly alveoli for diffusion. This provides humidity, warming or cooling to the inhaled gas like air, oxygen, and inhalational anesthetics.

The poster membranous wall of the tracheal provides a means for a food bolus to transit from the oral cavity through the esophagus to the stomach, while the trachea maintains its integrity on the anterior and lateral aspects due to the cartilaginous U-shaped rings.

Embryology

At 25 days gestation, the respiratory diverticulum originates between the IV and VI pharyngeal arches (V is rudimentary) at the laryngotracheal orifice from what becomes the esophagus in the original foregut. The esophagotracheal ridge eventually fuses together and forms the esophagotracheal septum. The proximal portion of the respiratory diverticulum forms the larynx and starts to branch at week four of gestation to form the right and left main bronchi. This continues to divide until approximately eight years of age.

Blood Supply and Lymphatics

The tracheal cartilages are dependent on lateral tracheal vascular pedicles which are derived from branches of the inferior thyroid, subclavian, superior intercostal, internal thoracic, innominate, brachiocephalic, superior and middle bronchial arteries. The arteries run longitudinal to the trachea and branch off in every intercartilaginous ligament to supply the cartilage and mucosa of the trachea. Esophageal arteries branch off to supply the posterior wall of the trachea.

Lymphatic drainage of the trachea is made up of pretracheal, paratracheal, and inferior deep cervical nodes. The lymphatic drainage path from distal to proximal in the lung is as follows: pulmonary and intrapulmonary nodes; bronchopulmonary and hilar nodes; inferior tracheobronchial (carina) and superior tracheobronchial nodes; paratracheal nodes; inferior deep cervical nodes. Some drainage will also occur through the aortic node.

Nerves

The vagus nerve (or tenth cranial nerve (CN X)) enters the superior mediastinum along bilateral common carotid arteries at the lateral borders. In the superior mediastinum, the left vagus nerve gives off the left recurrent laryngeal nerve. This nerve loops underneath the aorta, lateral to the ligament arteriosum and courses superior in the lateral groove between the esophagus and trachea. The right recurrent laryngeal nerve ascends on the contralateral side in the groove of the trachea and esophagus. Both recurrent laryngeal nerves supply parasympathetic (secretory glands), sensation and motor innervation to the trachea. Sympathetic nerves from the middle cervical ganglion are responsible for bronchodilation and reduced secretions.

Muscles

The trachea’s posterior wall contains a smooth muscle called the trachealis muscle. Adjacent and directly posterior to the trachea is the esophagus.

Physiologic Variants

Tracheoesophageal Fistula

A tracheoesophageal fistula (TEF) results from the abnormal division of the foregut into respiratory and esophageal portions. This condition is likely caused by a spontaneous deviation of the tracheoesophageal septum. It is important to note tracheoesophageal fistulas have a VACTERL association component (vertebral anomalies, anal atresia, cardiac defects, tracheoesophageal fistula, esophageal atresia, renal anomalies, and limb defects).[4][5][6][7]

Five Types of TEFs

Type A consists of a missing section of the esophagus resulting from atresia. The outcome is a blind-ending esophagus and a blind starting esophagus. Neither have any tracheal connection.

Type B entails of the upper esophagus forming a fistula with the trachea and a blind starting esophagus without any tracheal connection.

Type C (most common of TEFs 90%) consists of a blind-ending esophagus with no tracheal connection and a tracheobronchial fistula formed from the lower esophagus. If the bronchial component is present, the fistula will most likely form from the right bronchus.

In Type D, the upper and lower esophagus is not connected; however, both the upper and lower portions have a fistula connecting to the trachea.

Type E (also known as H-type due to forming the letter H) consists of a failure of the mid portion of the esophagus to separate from the trachea.

Tracheal Stenosis

Tracheal stenosis is a narrowing of the airway that could potentially lead to complete obstruction and therefore the cessation of ventilation. This condition can be congenital or develop later in life due to adjacent structures compressing the trachea, accumulation of granulation tissue, or edema from trauma, infection, or hemorrhage.

Tracheal Webs

Tracheal webs are short areas of stenosis that are usually treated with dilation, endoscopic lasers, or surgical excision.

Tracheomalacia

Tracheomalacia is a congenital or acquired weakness of the trachea that occurs from either weakening of the cartilage causing an anterior collapse, or a membranous weakening that collapses posteriorly. If the weakness extends into the bronchi, it is termed tracheobronchomalacia.

Tracheal Agenesis

Tracheal agenesis is a rare congenital deficiency which is often a fetal anomaly. Diagnoses would be most likely made through ultrasound at prenatal visits.

Surgical Considerations

As with all surgical procedures involving the airway, surgeons must always exercise caution. The surgeon should always be ready to perform an emergency airway if it becomes compromised.[8][9][10]

Tracheostomy is the creating of an opening connecting the anterior neck to the trachea to bypass the oral pharynx, pharynx, and larynx. This may be performed under local anesthetic or general anesthesia. Caution must be used during the procedure to prevent an airway fire. Inspired oxygen should be less than 30%, and the surgeon should be entering the trachea with a scalpel and no electrocautery.

Anterior mediastinal mass provides multiple changes to the anesthetic provider. He or she must always evaluate the patient’s symptoms to assess airway patency before surgery to determine if the patient can be safely induced or if other interventions must be performed. One should assess how severe the mass is compressing the trachea through the use of imaging. If the patient cannot keep their airway patent while sleeping or lying flat, an awake fiber-optic intubation should be performed. If the mass compresses the trachea distal to the endotracheal tube, initiation of bypass or extracorporeal membrane oxygenation must be readily available. Emergency airway methods are unlikely to relieve this obstruction in the thoracic cavity, and further advancement of the tube may still not relieve the obstruction.

Tracheal rupture may be caused by infection, trauma, or ulcerations. A tracheal stent is one type of treatment that could be utilized depending on the severity. Placement of a tracheal stent with a rigid bronchoscope can give rise to some anesthetic difficulties to adequately ventilate and provide inhalational anesthetic to the patient. Jet ventilation may be utilized, and careful visualization of chest rise and retraction should be noted ensuring adequate ventilation. One may also use total intravenous anesthetic because the use of inhalation anesthetic gases will be limited during the use of jet ventilation.

Clinical Significance

The right bronchus deviates from the trachea at 25 degrees from the midline, and the left bronchus deviates at a 45 degree from midline making aspiration and intubation into the right bronchus more common.

It should be noted that the conducting airways provide no gaseous exchange. This creates a physiologic dead space which constitutes approximately 150 ml. This is the reason EtCO2 will be slightly less than PaCO2 with invasive ventilation. The reason this difference occurs is dead space dilutes the amount of carbon dioxide truly exhaled.

Tracheitis is inflammation of the trachea and may last one to three weeks occurring more frequently in the winter and fall. It is thought to be mostly viral; however, the exact cause is unknown. Diagnosis is made when the primary symptom is a cough without radiological evidence of pneumonia and does not meet systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) criteria.

The tracheal deviation may be seen on clinical examination or radiological studies. This deviation aids the provider with useful information about the patient and usually indicates an underlying process causing an increase in intrathoracic pressure. This could result in hemodynamic collapse and must be evaluated and treated promptly. Some underlying pathologies that may cause tracheal deviation include tension pneumothorax, hemothorax, pleural effusion, primary malignancies, metastases, scoliosis, atelectasis, or prior pneumonectomy.

A variety of tumors can arise from the respiratory system or adjacent structures, all of which alter the anatomy. It is essential to perform an adequate airway exam and that an appropriate plan is in place if the airway becomes compromised.

Other Issues

After intubation with an endotracheal tube, during cardiopulmonary resuscitation, eight to ten respirations a minute are initiated. If there is no intravenous (IV) access, or if access is lost, epinephrine, which is absorbed rapidly, can be administered into the trachea. The required dose is 2.0 mg to 2.5 mg (two to 2.5 times the intravenous dose), and frequency is the same per advanced cardiovascular life support (ACLS) guidelines. Optimum dosing through the endotracheal tube (ETT) remains controversial.

Other drugs that may be administered in the trachea include naloxone, atropine, vasopressin, epinephrine, and lidocaine.

Endotracheal cuffs are inflated within the trachea and if overinflated can cause tracheal ischemia or rupture. The cuff helps prevent aspiration during surgery but does not completely prevent aspiration.