Continuing Education Activity

This activity reviews salient details regarding bile duct access via needle puncture through the body wall and liver via percutaneous transhepatic cholangiography (PTC). This activity discusses the indications, contraindications, adverse events, and other key elements of use of PTC in the clinical setting as it relates to the essential points needed by members of an interprofessional team managing the care of patients that require this procedure.

Objectives:

- Describe the indications and contraindications for PTC.

- Explain patient preparation for PTC.

- Identify complications from PTC.

- Summarize the clinical benefits that can be achieved by PTC using an interprofessional team.

Introduction

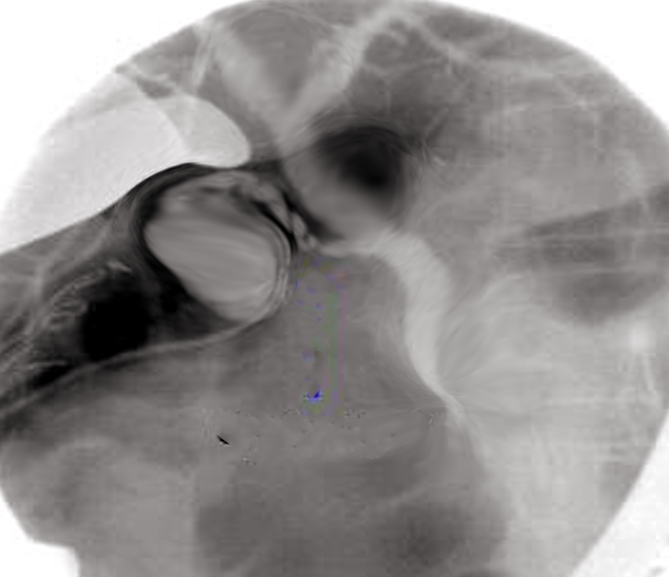

Percutaneous transhepatic cholangiography (PTC) is a procedure performed for diagnostic and/or therapeutic purposes by first accessing the biliary tree with a needle and then usually shortly after that with a catheter (percutaneous biliary drainage or PBD). At some point during the procedure, contrast is injected into one or more bile ducts (cholangiography) and also possibly into the duodenum. PTC may be performed with fluoroscopic guidance only or also with ultrasound (US) guidance.[1][2][3]

Anatomy and Physiology

The central outlet of bile from the liver is the proper hepatic duct, while both the inlet and outlet duct of the gallbladder is the cystic duct. The sphincter of Oddi, under neurologic and endocrine stimulation, serves as the controlling valve for either the release of bile into the duodenum or for the retention of bile within the ducts and resultant backflow of bile into the gallbladder via the cystic duct. The stretch of duct distal to the union of the cystic duct with the proper hepatic duct is termed the common bile duct (CBD). This extrahepatic anatomic configuration, on the one hand, is almost invariable.

The configuration of the ducts within the liver, on the other hand, is variable (see diagram "bile duct anatomy"). The most common configuration, seen in about 50% of people, is a single duct draining the left lobe and a single duct formed by the union of an anterior and posterior duct draining the right lobe. The most common variant of this configuration is a right anterior segmental branch that drains directly into the CBD and a right posterior segmental branch that drains elsewhere. The right anterior duct (draining segments V and VIII) usually courses in a somewhat craniocaudal orientation, while the right posterior duct (draining segments VI and VII) usually courses more lateromedially.

Indications

Although PTC serves a diagnostic function as its name implies, less invasive procedures to image the bile ducts and adjacent tissues should be considered as first-line procedures for diagnostic purposes. [4]These include:

- US

- Computed tomography (CT)

- Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) including cholangiopancreatography (MRCP)

- Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP)

PTC is performed mostly for therapeutic purposes in the setting of suspected or already confirmed bile duct obstruction and/or to obtain diagnostic specimens, particularly when ERCP is not an option or has been unsuccessful.

The list of diseases that obstruct the drainage of bile can be divided into 2 categories: malignant and benign. In the United States, malignant etiologies are more common, particularly cholangiocarcinoma. The most common benign diseases causing bile duct stenosis are liver transplant related stenoses and sclerosing cholangitis.

There are no medical society guidelines that provide objective laboratory, symptom, or physical exam grades or cutoffs for assessing the severity of bile obstruction in a systematic fashion or that comprehensively address, with multiple algorithms, a standard for employing PTC. However, some medical societies provide general guidelines in some specific situations. In the setting of a suspected malignant stricture, the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) states that jaundice in and of itself is an indication for intervention to relieve the stricture. The NCCN otherwise only addresses PTC in the specific setting of a planned partial hepatectomy of the tumor-containing segment or segments. The anticipated remaining portion of the liver is termed the future liver remnant (FLR). In a person with a predicted inadequate sized FLR, the NCCN recommends that any obstructed ducts in the FLR be drained prior to hepatectomy.

European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy 2012 guidelines recommend preoperative drainage for patients with potentially resectable malignant CBD obstruction only in patients who are candidates for neoadjuvant chemotherapy/radiation, have acute cholangitis, have intense pruritus, and surgery can be delayed (Recommendation grade A).

- Nausea, anorexia, pain, and pruritis are the most common symptoms of bile duct obstruction. Patients may present with any one or multiple of these. No objective criteria have been proposed on how severe the clinical symptoms should be prior to indicating PTC.

- PTC may be performed to help to divert bile away from the site of a biliary leak, for example, post cholecystectomy.

- PTC is an alternative means of accessing the bile ducts in situations more commonly performed by ERCP, such as bile duct stone or bile duct stent retrieval when ERCP is not possible (for example, post-Whipple procedure) or has failed.

Sepsis believed to be related to bile duct obstruction is an indication of an attempt at the relief of the obstruction. Intravenous (IV) fluids and antibiotics should be started first. No evidence-based studies indicate whether drainage should be attempted immediately or after a short delay, such as after 8 to 12 hours, after initiation of antibiotics.

Some surgeons prefer having bile duct obstruction relieved before performing a non-emergent operation or a re-operation. For example, in the setting of inadvertent CBD ligation, the intrahepatic bile ducts can be drained percutaneously prior to the corrective surgery.

Contraindications

PTC should be avoided or delayed in certain circumstances. As for all procedures, it is advisable to start with the least potentially harmful manner of therapy. It may not be advisable or even possible to correct multisegmental obstructions with multiple areas of narrowing and to instead correct only the minimum needed to provide a tolerable therapeutic result. The procedure should be reconsidered if the patient has a predicted very short-term survival.

ERCP should be considered as potential first-line therapy for stenoses/obstructions that are reachable via this method, as ERCP could prevent unnecessary complications from hemorrhage and the possible need for placement of a catheter that can only drain bile externally. The NCCN 2017 guidelines recommend ERCP as first-line intervention for extrahepatic ductal lesions. There are no current medical society guidelines for differentiating which patients should have ERCP attempted first for intrahepatic ductal lesions.

Attempting PTC on a non-dilated ductal system, such as in the setting of the goal of diverting bile away from a CBD or cystic duct leak, can greatly increase the chance of failed access. PTC may be deferred temporarily if there is a chance that the ducts may increase in size with a short delay.

Certain factors should be taken into consideration before attempting the procedure, such as risks for hemorrhage and complications from sedation, with such risks mitigated if possible. The Society of Interventional Radiology (SIR) provides a list of recommendations for the cessation of antiplatelet and anticoagulant medications for interventional radiology procedures, which it categorizes based on hemorrhage risks from level 1 to level 3. The SIR classifies PTC as a level 2 procedure. For such procedures, the SIR recommends an INR of no more than 1.5 and a platelet count of at least 50,000 cells/microliter.

Further issues that could be considered relative contraindications are discussed below in the section on preparation.

Preparation

Cross-sectional imaging is not necessary but allows for pre-procedural planning and may be the difference maker between a successful and an unsuccessful procedure. For example, it can show what type of ductal drainage pattern the patient has and whether a right or left lobe approach should be considered initially. Radionuclide scintigraphy with technetium 99-m and a hepatobiliary agent such as an iminodiacetic acid (HIDA scan) may be used to confirm the presence or absence of a bile duct leak.

All patients receive antibiotics to cover gram-negative bacteria regardless of infectious symptoms or lack thereof. Some institutions also cover for gram-positive and/or anaerobic bacteria. The SIR guidelines list several regimens for consideration. For example, regimens used at some institutions include ampicillin (1 g) and gentamicin (80 mg) or piperacillin/tazobactam (3.375 g to 4.5 g) 1 hour before the procedure.

As soon as a patient is referred for biliary drainage in the setting of malignancy, that person should be started on IV fluids, as it should be assumed that he/she is dehydrated (which increases the risk of hepatorenal failure) due to volitional and/or iatrogenic nothing by mouth (NPO status).

Coagulation parameters outside of SIR-recommended parameters should be corrected. If the INR is elevated before an emergent need for hepatic puncture, then fresh frozen plasma delivery should be considered before, during, and after the procedure, as the half-life of fresh frozen plasma is short.

It may be prudent to have an anesthesiologist consulted and available during the procedure if necessary for patients with hemodynamic liability or risk factors for undergoing sedation, such as American Society of Anesthesiology physical status class 4 or above or an "advanced airway."

Complications

The SIR has published complication rates for PTC and PBD. The rate of major complications is around 2% to 10%. Major complications include inducing sepsis, other severe infection (such as an abscess), bile leak/biloma, hemorrhage (subcapsular hematoma, pseudoaneurysm), pneumothorax, and death.[5][1][3]

Transgression of blood vessels during PTC is to be expected. Coagulation usually occurs successfully, and hemorrhage ceases entirely within 2 to 3 days. Bleeding through the catheter can occur if a catheter side hole is left in communication with a hepatic vessel or if a pseudoaneurysm develops.

Hemodynamically Stable

In hemodynamically stable patients, if hemorrhage is obvious (such bright red pulsatile blood is coming out of the tube), then the patient should be taken for emergent angiographic embolization.

If hemorrhage is suspected, such as from observing hemobilia, a falling hemoglobin level, or unstable vital signs, then CT angiography (CTA) can be considered as a first-line diagnostic tool. Digital subtraction angiography (DSA) via arterial puncture can be performed thereafter for embolization treatment if evidence of bleeding is seen on the CTA. However, whenever there is strong clinical suspicion of bleeding in the absence of hemorrhage seen on CTA, then a fluoroscopic tractogram should be performed next.

If no vessels are opacified or if the drainage catheter sideholes are found to lie outside biliary tract, then the catheter should be repositioned and the tractogram repeated. Angiographic with possible embolization should be considered. If a vein is opacified, then the catheter should be upsized to tamponade the vein. Time should be given to see if the intervention worked. If an artery is opacified, then the catheter should be upsized to tamponade the artery. If blood can still be aspirated through the larger catheter, then angiographic embolization of the hepatic artery branch involved should be performed urgently.

Hemodynamically Unstable

A decision must be reached between the radiologist and surgeon whether the patient should go to surgery, to angiography, or both if angiography can be performed in the operating room.

Bleeding

- Tumor bleeding can occur, particularly in hilar tumors. It is difficult to treat and may not respond to embolization or to the placement of a larger catheter thereby requiring surgery.

- In rare instances, bleeding can occur after planned catheter removal. In this situation, the bleeding is almost always venous and cannot be addressed through angiography (i.e., arteriography). An attempt can be made to embolize the initial tract via ERCP or a second PTC.

Bile lining the skin, peritoneum, or pleura even in small amounts can cause severe pain in some patients, while a large leak may cause no pain in others. If bile leaks out of or around the catheter into the abdomen (peritonitis) or chest (pleuritis), then the catheter should be repositioned, unclogged, and/or upsized to tamponade the leak. Biloma and/or subcapsular hematoma formation does not in and of itself require remediation because the body can resorb the fluid, but if the fluid becomes painful or infected, then it can be percutaneously drained.

If electrolyte depletion occurs due to high-output external drainage, then the electrolytes should be replaced and considerations should be made on converting the catheter to internal drainage as soon as possible.

PTC +/- PBD provides a conduit for bacteria to enter the biliary tract from an external source. Preventive measures include routine catheter exchange every 2 to 3 months and using a catheter that has a good chance at remaining patent (e.g., at least 12 Fr caliber). Cholangitis is treated with antibiotics.

Although PTC may be performed to treat the obstruction that is the cause of sepsis, PTC itself may also cause sepsis. Antibiotics, IV fluids, oxygen, and vasopressors in the setting of an intensive care unit should be considered.

Catheter Dislodgement

Catheter dislodgement can occur even with educating the patient regarding measures to avoid allowing traction to be placed on the catheter. A safety stitch at the skin surface and/or a catheter with a self-retaining mechanism are both usually used. The creation of a stable patent tract by the initial drainage catheter takes 4 to 6 weeks, so this initial time is particularly important to take measures to prevent catheter dislodgement.

If the catheter has become partially dislodged, then it is usually able to be replaced fairly easily over a guidewire. If it has retracted out of the liver entirely, then it becomes much more challenging to replace. If the catheter tract can be opacified with contrast, then often an angiographic type catheter and a guidewire can be used to negotiate the transhepatic tract and then reinsert a new drainage catheter through the original tract.

Clinical Significance

PTC and PBD may be a necessary step to the least invasive method for relieving a patients nausea, anorexia, pain, or jaundice. It can be the best procedure to enable subsequent removal of bile duct stones, procural of a tissue diagnosis, or treatment of a bile duct stricture. A surgeon may request this on the thought that it could reduce surgical complications, although this has yet to be proven.

The technical success rate for PBD in dilated ducts is usually over 90%. The issue of PBD success in nondilated ducts is more controversial, with some authors indicating a success rate of about 65% to 80% and the SIR indicating that 65% success is a reasonable goal (Saad 2010). The SIR states that if PTC can be performed successfully in nondilated ducts that the minimum subsequent threshold for success at PBD should be 70%.[6][7][8]

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Healthcare Team

Management of patients with hepatobiliary pathology can be optimized with an interprofessional approach by hepatalogists, hepatic surgeons, interventional radiologists, and specialty-trained radiology nurses. Patients in whom indwelling catheters are left often undergo extensive care and education by nurses and other healthcare professionals, such as physician assistants and radiologic technologists. The nurse should also assist in the coordination of follow-up care with the clinical team. Patients in whom biliary stents are placed usually require continued monitoring by gastroenterologists/hepatologists and diagnostic radiologists.

Outcomes Summary

Percutaneous biliary access and imaging leads to intended beneficial outcomes in the majority of cases. Clinicians taking care of patients with biliary tract pathology should be aware of signs and symptoms that indicate invasive cholangiography to be the next best step in patient care and that can occur as sequelae from the procedure.