Introduction

Essential amino acids, also known as indispensable amino acids, are amino acids that humans and other vertebrates cannot synthesize from metabolic intermediates. These amino acids must be supplied from an exogenous diet because the human body lacks the metabolic pathways required to synthesize these amino acids.[1][2] In nutrition, amino acids are classified as either essential or non-essential. These classifications resulted from early studies on human nutrition, which showed that specific amino acids were required for growth or nitrogen balance even when there is an adequate amount of alternative amino acids.[3] Although variations are possible depending on the metabolic state of an individual, the general held thought is that there are nine essential amino acids, including phenylalanine, valine, tryptophan, threonine, isoleucine, methionine, histidine, leucine, and lysine. The mnemonic PVT TIM HaLL ("private Tim Hall") is a commonly used device to remember these amino acids as it includes the first letter of all the essential amino acids. In terms of nutrition, the nine essential amino acids are obtainable by a single complete protein. A complete protein, by definition, contains all the essential amino acids. Complete proteins usually derive from animal-based sources of nutrition, except for soy.[4][5] The essential amino acids are also available from incomplete proteins, which are usually plant-based foods. The term "limiting amino acid" is used to describe the essential amino acid present in the lowest quantity in a food protein relative to a reference food protein like egg whites. The term "limiting amino acid" may also refer to an essential amino acid that does not meet the minimal requirements for humans.[6]

Fundamentals

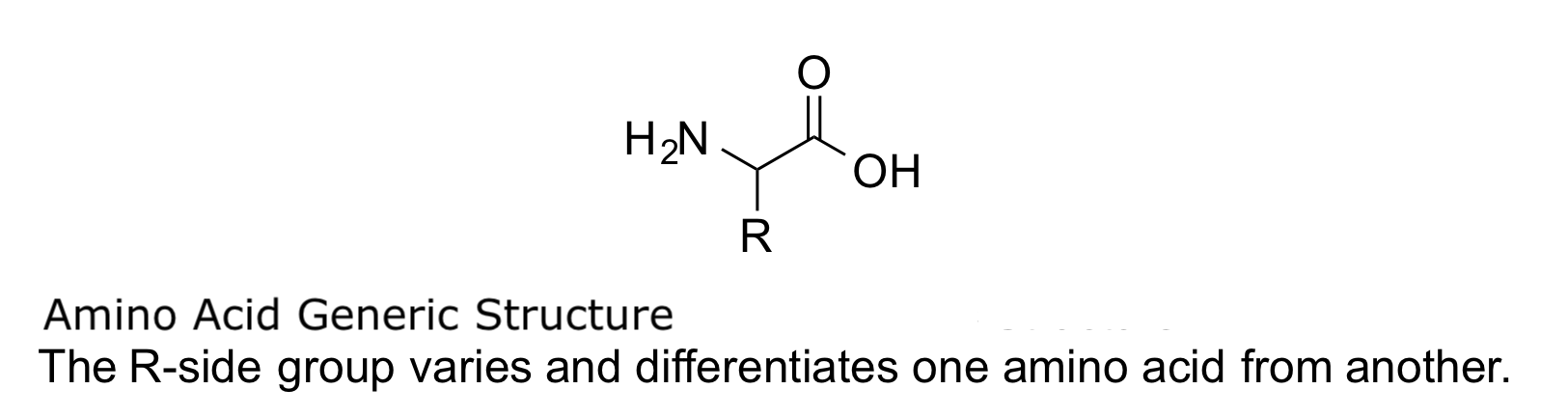

Amino acids are the basic building blocks of proteins, and they serve as the nitrogenous backbones for compounds like neurotransmitters and hormones. In chemistry, an amino acid is an organic compound that contains both an amino (-NH2) and carboxylic acid (-COOH) functional group, hence the name amino acid. Proteins are long chains or polymers of a specific type of amino acid known as an alpha-amino acid. Alpha-amino acids are unique because the amino and carboxylic acid functional groups are separated by only one carbon atom, which is usually a chiral carbon. In this article, we will solely focus on the alpha-amino acids that make up proteins.[7][8]

Proteins are chains of amino acids that assemble via amide bonds known as peptide linkages. The difference in the side-chain group or R-group is what determines the unique properties of each amino acid. The uniqueness of different proteins is then determined by which amino acids it contains, how these amino acids are arranged in a chain, and further complex interactions the chain makes with itself and the environment. These polymers of amino acids are capable of producing the diversity seen in life.

There are approximately 20,000 unique protein encoding genes responsible for more than 100,000 unique proteins in the human body. Although there are hundreds of amino acids found in nature, only about 20 amino acids are needed to make all the proteins found in the human body and most other forms of life. These 20 amino acids are all L-isomer, alpha-amino acids. All of them, except for glycine, contain a chiral alpha carbon. And all these amino acids are L-isomers with an R-absolute configuration except for glycine (no chiral center) and cysteine (S-absolute configuration, because of the sulfur-containing R-group). It bears mentioning that the amino acids selenocysteine and pyrrolysine are considered the 21st and 22nd amino acids, respectively. They are more recently discovered amino acids that may become incorporated into protein chains during ribosomal protein synthesis. Pyrroloysine has functionality in life; however, humans do not use pyrrolysine in protein synthesis. Once translated, these 22 amino acids may also be modified via a post-translational modification to add further diversity in generating proteins.[8]

The 20 to 22 amino acids that comprise proteins include:

- Alanine

- Arginine

- Asparagine

- Aspartic Acid

- Cysteine

- Glutamic acid

- Glutamine

- Glycine

- Histidine

- Isoleucine

- Leucine

- Lysine

- Methionine

- Phenylalanine

- Proline

- Serine

- Threonine

- Tryptophan

- Tyrosine

- Valine

- Selenocysteine

- Pyrrolysine (not used in human protein synthesis)

Of these 20 amino acids, nine amino acids are essential:

- Phenylalanine

- Valine

- Tryptophan

- Threonine

- Isoleucine

- Methionine

- Histidine

- Leucine

- Lysine

The non-essential, also known as dispensable amino acids, can be excluded from a diet. The human body can synthesize these amino acids using only the essential amino acids. For most physiological states in a healthy adult, the above nine amino acids are the only essential amino acids. However, amino acids like arginine and histidine may be considered conditionally essential because the body cannot synthesize them in sufficient quantities during certain physiological periods of growth, including pregnancy, adolescent growth, or recovery from trauma.[9]

Mechanism

Although there are twenty amino acids required for human protein synthesis, humans can only synthesize about half of these required building blocks. Humans and other mammals only have the genetic material required to synthesize the enzymes found in the biosynthesis pathways for non-essential amino acids. There is likely an evolutionary advantage behind removing the long pathways required to synthesize essential amino acids from scratch. By losing the genetic material required to synthesize these amino acids and relying on the environment to provide these building blocks, these organisms can reduce energy expenditure, especially while replicating their genetic material. This situation provides a survival advantage; however, it also creates a dependency on other organisms for the essential materials needed for protein synthesis.[10][11][12]

Clinical Significance

The classification of essential and nonessential amino acids was first reported in nutritional studies done in the early 1900s. One study (Rose 1957), found that the human body was capable of staying in nitrogen balance with a diet of only eight amino acids.[13] These eight amino acids were the first classification of essential amino acids or indispensable amino acids. At this time, scientists were able to identify essential amino acids by conducting feeding studies with purified amino acids. The researchers found that when they removed individual essential amino acids from a diet, the subjects would be unable to grow or stay in nitrogen balance. Later studies found that certain amino acids are "conditionally essential," depending on the subject's metabolic state. For example, although a healthy adult may be able to synthesize tyrosine from phenylalanine, a young child may not have developed the required enzyme (phenylalanine hydroxylase) to perform this synthesis, and so they would be unable to synthesize tyrosine from phenylalanine, making tyrosine an essential amino acid under those circumstances. This concept also appears in different disease states. Basically, deviations from a standard healthy adult's metabolic state may place the body in a metabolic state that requires more than the standard-essential amino acids to be nitrogen balance. In general, the optimal ratio of essential amino acids and nonessential amino acids requires a balance dependent on physiological needs that differs between individuals. Finding the optimal ratio of amino acids in total parenteral nutrition for liver or kidney disease is a good example of different physiological states requiring different nutrient intakes. Therefore, the terms "essential amino acid" and "nonessential amino acids" may be misleading since all amino acids may be necessary to ensure optimal health.[1]

During states of inadequate intake of essential amino acids such as vomiting or low appetite, clinical symptoms may appear. These symptoms may include depression, anxiety, insomnia, fatigue, weakness, growth stunting in the young, etc. These symptoms are mostly caused by a lack of protein synthesis in the body because of the lack of essential amino acids. Required amounts of amino acids are necessary to produce neurotransmitters, hormones, the growth of muscle, and other cellular processes. These deficiencies are usually present in poorer parts of the world or elderly adults with inadequate care.[2]

Kwashiorkor and marasmus are examples of more severe clinical disorders caused by malnutrition and inadequate intake of essential amino acids. Kwashiorkor is a form of malnutrition characterized by peripheral edema, dry peeling skin with hyperkeratosis and hyperpigmentation, ascites, liver malfunction, immune deficits, anemia, and relatively unchanged muscle protein composition. It results from a diet with insufficient protein but adequate carbohydrates. Marasmus is a form of malnutrition characterized by wasting caused by inadequate protein and overall inadequate caloric intake.[14]