Introduction

The thoracic wall is made up of five muscles: the external intercostal muscles, internal intercostal muscles, innermost intercostal muscles, subcostalis, and transversus thoracis. These muscles are primarily responsible for changing the volume of the thoracic cavity during respiration. Other muscles that do not make up the thoracic wall, but attach to it include the pectoralis major and minor, subclavius, and serratus anterior (anteriorly) and the primary costarum and serratus posterior superior and inferior (posteriorly). The muscles of the anterior thorax provide movements to the arm and shoulder while the muscles of the posterior thorax also help change thoracic volume during breathing and reinforce the thoracic wall. The diaphragm is another muscle in the thorax that serves as the main muscle of inspiration. It also makes up the floor of the thorax, thus separating the contents of the chest from those of the abdomen. Other minor accessory muscles that attach to the thorax include the scalene muscles and the sternocleidomastoid muscle, both of which may also minimally aid in respiratory efforts.

Structure and Function

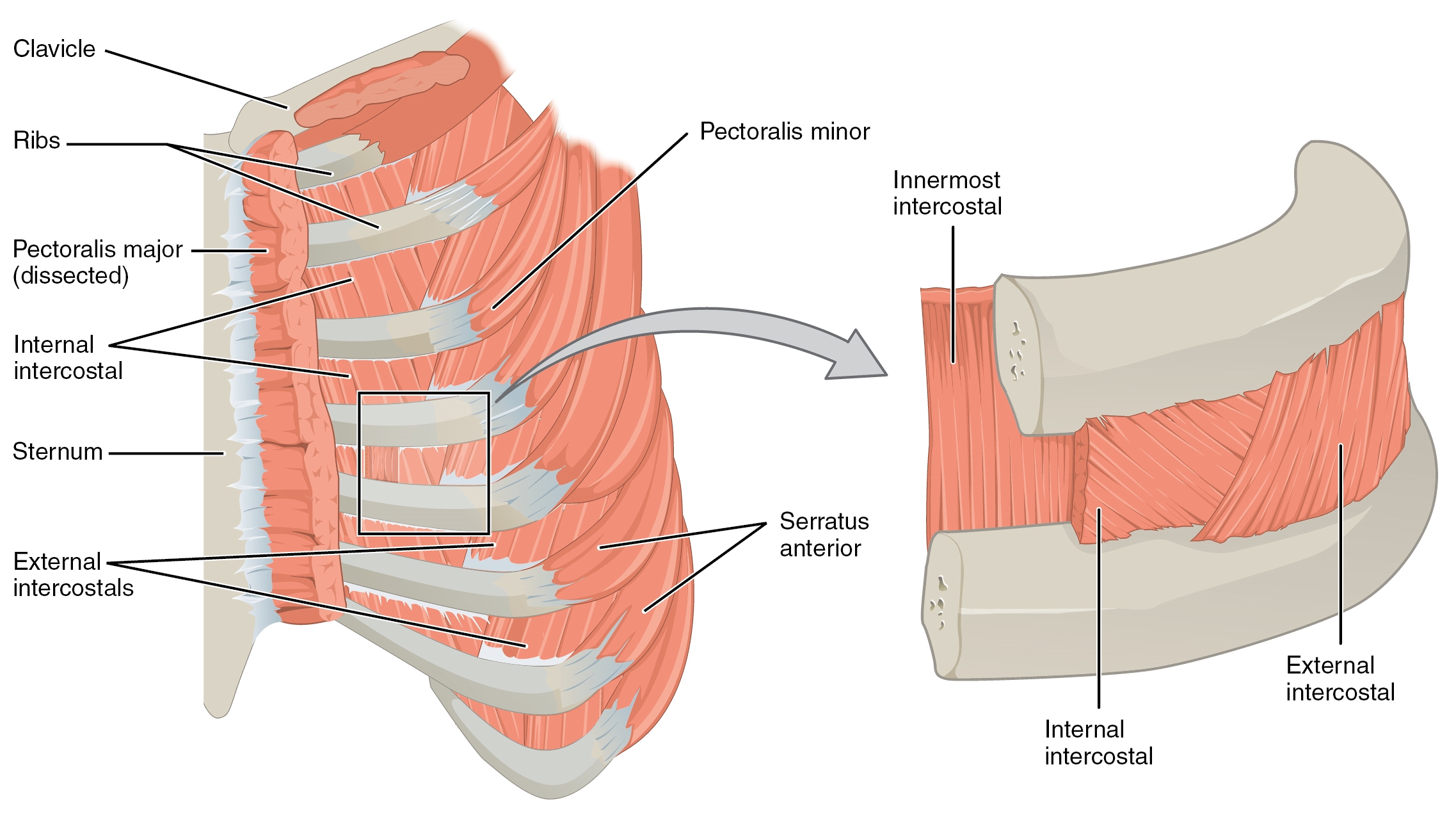

The muscles that make up the thorax wall include the three intercostal muscles (external, internal, and innermost), the subcostalis, and the transversus thoracis. Eleven pairs of intercostal muscles are in each of the intercostal spaces, arranged from superficial to deep. The most superficial layer is the external intercostal muscle, which originates from the inferior aspect of the rib above and inserts onto the superior aspect of the rib below in an inferomedial direction. These muscles extend from the rib tubercle posteriorly and attach to the costochondral junction anteriorly where they continue as thin connective tissue aponeuroses known as the anterior (external) intercostal membrane.

During inspiration, the external intercostals contract and raise the lateral part of the ribs, increasing the transverse diameter of the thorax in a bucket handle motion. The internal intercostal muscle forms the intermediate layer. These muscles originate from the lateral aspect of the costal groove of the rib above and insert into the superior aspect of the rib below in a direction perpendicular to the external intercostal muscles. This arrangement allows them to depress the ribs and subsequently reduce the thoracic volume during forced expiration. Further, these muscles extend from the sternum anteriorly to the rib cage posteriorly where they continue as the posterior (internal) intercostal membrane. The deepest layer of the thorax wall is made up of the innermost intercostal muscles. They originate from the medial aspect of the costal groove of the rib above and insert onto the internal aspect of the rib below. These muscles are lined internally by the endothoracic fascia, which appears just superficial to the parietal pleura of the lungs. They are thought to act with the internal intercostal muscle during forced expiration.[1][2]

In addition to the intercostal muscles, the subcostalis and the transversus thoracis also make up the thoracic wall. The subcostalis exists in the same layer as the innermost intercostal muscle and is present in abundance in the lower regions of the posterior thoracic wall. They originate from the internal aspect of one of the lower ribs and insert onto the internal aspect of the second or third rib below. The transversus thoracis also appears in the same space at the innermost intercostal muscle. They originate from the lower posterior sternum, spread across the inner surface of the thoracic cage, and inserts onto ribs 2 through 6. Both of these muscles aid in depressing the ribs during forced expiration.[2]

Muscles of the posterior thorax, such as the levatores costarum and serratus posterior superior and inferior, may also aid in respiration. The levatores costarum originates from the transverse processes of C7 to T11 and inserts onto the rib below. It minimally aids in inspiration via rib elevation. The serratus posterior superior attaches to ribs 2 through 5 and elevates them during inspiration whereas the serratus posterior inferior attaches the vertebrae to ribs 8 through 12 and depresses them during forced expiration.[2] These muscles, in conjunction with the muscles of the thoracic wall, help alter the thoracic volume during respiration and altogether reinforce the thoracic wall.

The major muscle of inspiration, however, comes from the diaphragm. The diaphragm is attached peripherally to the xiphoid process (sternal portion), the costal margin of the thoracic wall and lower sixth ribs (costal portion), and the lumbar vertebrae (lumbar part). During inspiration, the muscle contracts and pulls down its central tendon inferiorly, thus flattening the diaphragm - this action increases the vertical diameter of the thorax and increases the negative thoracic pressure, which ultimately draws air into the thoracic cavity. During expiration, the diaphragm relaxes and elevates, forcing the air with the lungs to be expelled from the body. Other accessory muscles that aid inspiration include the scalene muscles (helps elevate the first and second ribs) and sternocleidomastoid muscle (assists in raising the sternum). Besides respiration, the diaphragm also functions to aid abdominal straining and increase intra-abdominal pressure upon contraction during times of micturition, defecation, and even weightlifting.[2][3]

Other muscles of the thorax are involved in upper limb movement, which include the pectoralis major and minor, subclavius, and serratus anterior muscles. The pectoralis major originates from the medial half of the clavicle, anterior sternum, first seven costal cartilages, and aponeurosis of the external oblique and inserts on the lateral lip intertubercular sulcus of the humerus. It functions to flex, adduct, and medially rotate the arm at the glenohumeral joint. Its clavicular head causes flexion of the extended arm while its sternoclavicular head causes extension of the flexed arm.[4] The pectoralis minor muscle originates from the anterior surfaces of ribs 3 to 5 and the deep fascia overlying the related intercostal spaces and inserts on the coracoid process of the scapula. It functions mainly to depress the tip of the shoulder and protract the scapula. It may also assist respiratory efforts as an accessory muscle by lifting the third, fourth, and fifth ribs during inspiration.[2] The subclavius muscle originates at the costochondral junction of the first rib and inserts at the subclavian groove of the clavicle. It functions to stabilize the clavicle.[5]

The serratus anterior muscle originates on the superolateral surfaces of the first to eighth ribs or the first to ninth ribs at the lateral wall of the thorax and inserts along the superior angle, medial border, and inferior angle of the scapula. It mainly functions to protract the scapula as seen in punching, hence its colloquial nickname as the "boxer's muscle," thus facilitating scapular rotation. The serratus anterior may also assist in inspiratory efforts by elevating the ribs when the shoulder girdle is in a fixed position.[6]

Embryology

Skeletal muscle develops from the differentiation of mesoderm. During the fourth to eighth weeks of human development, paraxial mesoderm organizes itself into clusters alongside the neural tube to form somites. These somites then differentiate into two sets of cells: the dorsolateral dermomyotome and the ventromedial sclerotome. The dermomyotome goes on to form the skeletal muscle, including the muscles of the thorax, and the dermis of the skin while the sclerotome forms the axial skeleton.[1][4]

Blood Supply and Lymphatics

The intercostal arteries mainly supply the muscles of the thoracic wall and posterior thorax. Each intercostal space receives supply by three arteries (one posterior intercostal artery and two anterior intercostal arteries) that run in between the internal intercostal muscle and innermost intercostal muscle in the costal groove and anastomose laterally. The posterior intercostal artery of the first two intercostal spaces comes from the superior (supreme) intercostal artery, which subsequently arises from the costocervical trunk of the subclavian artery. The remaining posterior intercostal arteries from the third to eleventh intercostal spaces and a pair of subcostal arteries emerge directly from the descending thoracic aorta. Their corresponding veins drain into the azygos or hemiazygos veins. The anterior intercostal arteries of the first six intercostal spaces are branches of the internal thoracic artery, which come from the first portion of the subclavian artery. The remaining anterior intercostal arteries from the seventh to ninth intercostal spaces come from the branches of the musculophrenic artery, which is a terminal branch of the internal thoracic artery. Their corresponding veins drain into the internal thoracic or musculophrenic veins. The lymphatic drainage of the thoracic wall involves the parasternal lymph nodes and intercostal lymph nodes. The parasternal lymph nodes from the upper thorax drain into the bronchomediastinal trunk. The intercostal lymph nodes from the upper thorax also drain into the bronchomediastinal trunk, whereas the intercostal nodes from the lower thorax drain into the thoracic duct.[1][2]

The pectoralis major and minor muscles are supplied by the pectoral branch of the thoracoacromial trunk, which is the second branch of the axillary artery. Their venous drainage comes from the pectoral vein via the subclavian vein.[4] The subclavius receives vascular supply by the clavicular branch of the thoracoacromial trunk. The serratus anterior is supplied by the lateral thoracic artery, the superior thoracic artery, and the thoracodorsal artery.[6] Lymphatic drainage of the superficial regions of the thoracic wall typically involve the axillary lymph nodes or the parasternal nodes.

Last, the diaphragm is supplied by multiple arteries that include the musculophrenic artery branch of the internal thoracic artery, superior phrenic artery branch of the aorta, lower five intercostal arteries and subcostal artery, and the inferior phrenic artery.[3] Similar to its level of blood supply, there is also an abundant supply of lymph nodes that drain the diaphragm towards the mediastinal lymph node centers connecting to the bloodstream via the thoracic duct.[7]

Nerves

The muscles that comprise the thoracic wall and the posterior thorax are innervated by the intercostal nerves, which mainly come from the anterior rami of spinal nerves T1 to T11. The anterior ramus of spinal nerve T12 is a subcostal nerve. Each intercostal nerve supplies a dermatome and a myotome. Their afferent fibers provide sensory information to the overlying skin while their efferent fibers conduct motor information to the muscles of inspiration. Of note, only a portion of the anterior ramus of spinal nerve T1 forms the lower trunk of the brachial plexus whereas the remaining intercostal nerves do not form plexuses.[1][2]

Innervation to the muscles of the anterior thorax arises from different branches of the brachial plexus. Innervation of the pectoralis major is by both the lateral pectoral nerve, which innervates the clavicular head, and the medial pectoral nerve, which innervates the sternocostal head. The pectoralis minor receives its innervation by the medial pectoral nerve. The lateral pectoral nerve branches from the lateral cord of the brachial plexus while the medial pectoral nerve comes from the medial cord.[4][8] The nerve to the subclavius innervates the subclavius muscle, which arises from the superior trunk of the C5 to C6 nerve roots. If present, the accessory phrenic nerve, mostly a C5 contribution, may also provide motor innervation to the subclavius muscle.[5] Last, the serratus anterior is innervated by the long thoracic nerve, which originates from the anterior rami of C5 to C7.[6]

Innervation to the diaphragm comes from both the right and left phrenic nerves, which originate from the anterior rami of C3 to C5. The phrenic nerve provides both the motor innervation to allow the diaphragm to contract during inspiration and sensory innervation to the parietal pleura and peritoneum covering the central aspect of the diaphragm. The lower six intercostal nerves provide sensory innervation to the periphery of the diaphragm.[3][5]

Muscles

The muscles of the thorax discussed in this article include the following:

- Thoracic Wall

- Intercostal muscles

- External intercostal muscle

- Internal intercostal muscle

- Innermost intercostal muscle

- Subcostalis

- Transversus thoracis

- Posterior Thorax

- Levatores costarum

- Serratus posterior superior and inferior muscles

- Anterior/Superficial Thorax

- Pectoralis major and minor muscles

- Subclavius

- Serratus anterior

- Floor

Physiologic Variants

Multiple studies have reported the existence of anatomical variations of the muscles of the thorax either in the case of supernumerary muscles or congenital anomalies. The sternalis muscle is a rare supernumerary muscle variant of the anterior thoracic wall found in 8% of the population that lies vertically between the superficial fascia and the pectoral fascia, parallel to the right sternal margin. It measures at approximately 7.0 cm in length and 2.9 cm in width.[9] The sternalis muscle may present either unilaterally (4.5%) or bilaterally (less than 1.7%) and is thought to participate in shoulder joint movement or play an accessory role in lower chest wall elevation. There is still much disagreement about its innervation and embryological origin. Some reports have found that the muscle receives its innervation either from the external or internal thoracic nerves (55%), the intercostal nerves (43%), or both (2%). Moreover, some studies have postulated that it is a derivative of the hypaxial myotomes or the dermomyotomes from which the ventral and lateral body wall muscles of thorax and abdomen develope. Meanwhile, other studies endorse that the muscle develops either from the rectus abdominis sheath or from the pectoralis major as a result of a defect in the muscle patterning.

Cases have never reported any clinical symptoms related to the sternalis muscle; however, its existence may present alterations in the electrocardiogram or cause misdiagnoses of breast masses (e.g., breast carcinoma or hematoma) on routine mammography due to its parasternal location and relative unfamiliarity among radiologists. It has the potential to interfere with and prolong breast and cardiothoracic surgeries if undetected preoperatively. If it is detected preoperatively, surgeons can use the sternalis muscle as a muscular flap in reconstructive surgeries of the anterior chest wall, head and neck, and breast.[10][11]

Anatomical variations of the thorax muscles may also arise as a result of varying degrees of congenital anomalies. Poland syndrome is characterized by the absence of the sternocostal head of the pectoralis major muscle along with variations of hypoplasia or absence of the pectoralis minor muscle and even digital anomalies. Other anomalies described in Poland syndrome include the absence or hypoplasia of the ipsilateral breast, excavatum deformities, and rib aplasia. These defects are most commonly unilateral and typically found on the right side, although some studies have reported the rare existence of bilateral manifestations. Many variations of the syndrome have been described and range from cases of mild hypoplasia of the pectoralis major muscle to cases of severe hypoplasia of the thoracic wall.[12]

Surgical Considerations

Surgical interventions that involve the thorax muscles typically involve chest tube placement and needle therapy for either decompression or anesthesia.[1][2]

- Tube thoracostomy is performed to evacuate pathological air or fluid from the pleural cavity. A chest tube is usually placed between the mid- to anterior axillary line at the level of the fourth or fifth intercostal space above the rib to lessen the risk of damaging the blood vessels and nerves that run on the inferior aspect of each rib. Once the incision is made and the tube inserted, it will pierce the skin, superficial fascia, serratus anterior muscle, external intercostal muscle, internal intercostal muscle, and innermost intercostal muscle to ultimately reach the parietal pleura.

- Needle thoracostomy is another decompressive therapy, typically done in cases of tension pneumothorax, that is performed similarly to tube thoracostomy. Needle placement may be at either the second intercostal space at the midclavicular line or the fourth and fifth intercostal spaces at the anterior axillary line above the rib.

- Intercostal nerve block is usually done to alleviate pain associated with rib fractures or even herpes zoster. The needle is inserted below the rib and penetrates through the layers of the skin, superficial fascia, serratus anterior muscle, external intercostal muscle, and internal intercostal muscle, ultimately targeting the intercostal nerve for anesthesia. Most importantly, the surgeon must also anesthetize the adjacent intercostal nerve to achieve pain relief due to the presence of nerve collaterals and considerable overlapping of contiguous dermatomes.

Clinical Significance

Respiratory muscles have obvious implications for sustaining life and performing daily activities. The use of accessory muscles to aid respiratory efforts can be a normal finding during times of strenuous activity requiring high physiologic demand such as exercise or even singing. However, their presence in patients at rest may suggest a pathological cause such as asthma attack, which requires further evaluation, medical management, and treatment. Examples of accessory respiratory muscles include scalene muscles, sternocleidomastoid muscles, internal intercostals, transversus thoracis, pectoralis major and minor muscles, serratus anterior, serratus posterior superior and inferior, latissimus dorsi, trapezius, and the muscles of the abdomen.[2]