Continuing Education Activity

Chiari 2 malformation is a relatively common congenital malformation of the posterior fossa. Chiari 2 malformation is almost always associated with myelomeningocele and is characterized by caudal displacement of the cerebellar vermis, brainstem, and fourth ventricle. Chiari 2 malformation can be associated with numerous additional findings, most commonly hydrocephalus and syringomyelia. This disorder can have severe morbidity and mortality if it is not identified and treated promptly. The natural history of patients with Chiari 2 malformation is quite severe, with medullary symptoms remaining the leading cause of death.

Chiari 2 malformation may present a variety of clinical manifestations, which can include spinal symptoms secondary to myelomeningocele, tethered cord syndrome or syringomyelia, symptoms of secondary hydrocephalus, brainstem symptoms, or those due to lower cranial nerve dysfunction. Management of Chiari 2 malformation depends on the extent of the craniospinal malformation and its associated neurological impairments. This activity for healthcare professionals aims to enhance learners' competence in selecting appropriate diagnostic tests, managing Chiari 2 malformation, and fostering effective interprofessional teamwork to improve outcomes.

Objectives:

Identify the etiology of Chiari 2 malformation.

Implement recommended evaluation strategies for patients with Chiari 2 malformation.

Apply evidence-based management strategies for patients with Chiari 2 malformation.

Collaborate with the interprofessional team to improve care coordination for patients with Chiari 2 malformation.

Introduction

At the end of the nineteenth century, the pathologists Julius Arnold (1835-1915) and Hans Chiari (1851-1916) described a complex clinical and pathological condition involving deformity of the cerebellum and brainstem in children. Chiari malformations are now defined as a spectrum of hindbrain abnormalities involving the cerebellum, brainstem, skull base, and cervical cord. According to the type of herniation of the brain tissue displaced in the spinal canal and the characteristics of the anomalies of the brain or spine development, 4 types of Chiari malformations have been classified. Together with basilar invaginations, Chiari malformations represent the most common craniocervical junction malformations seen in adults.

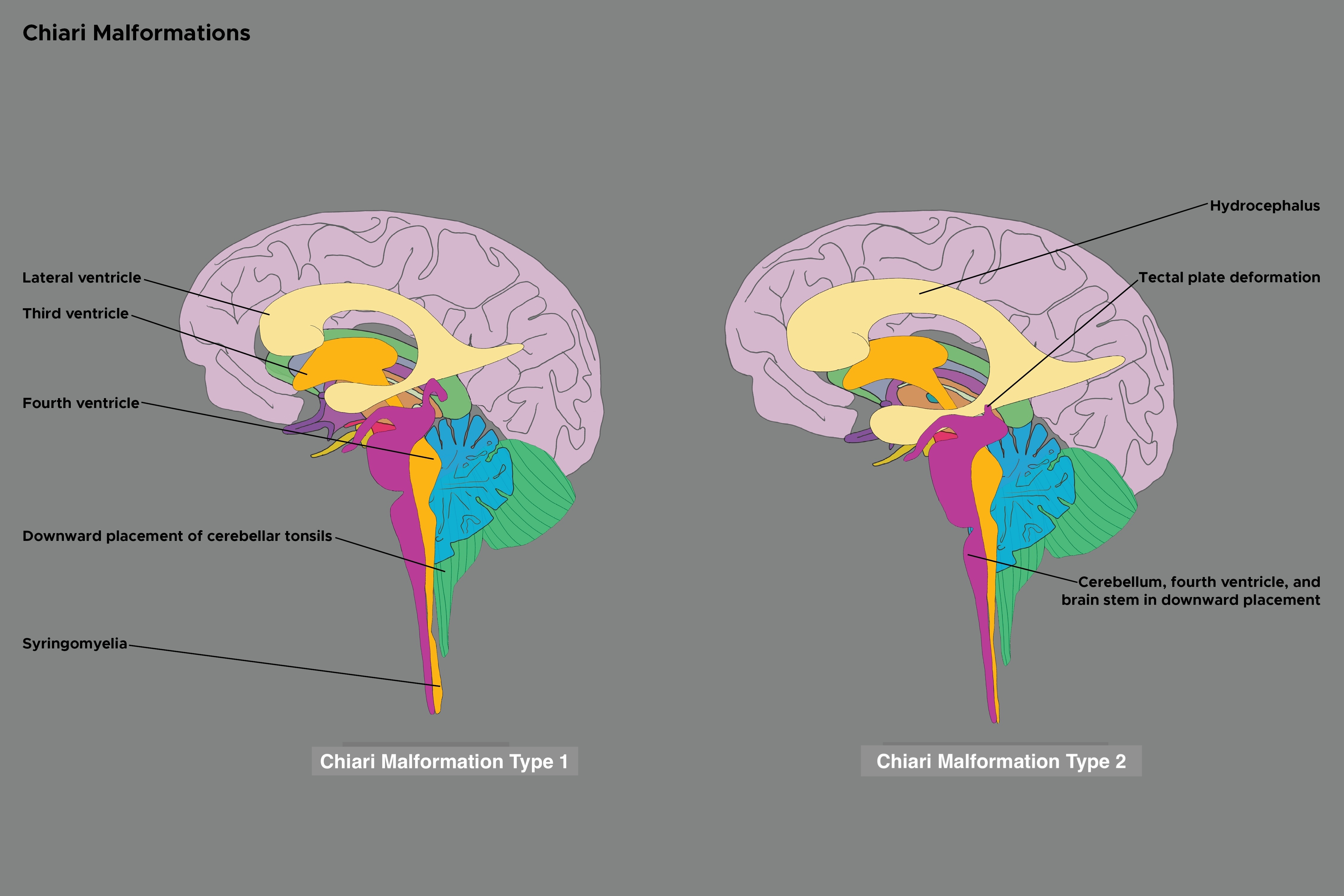

Chiari malformation type 2 or Chiari 2 malformation, commonly referred to as Arnold-Chiari malformation, is usually associated with spina bifida and is characterized by caudal displacement of the cerebellar vermis, brainstem, and fourth ventricle.[1][2] Despite its name, rather than a continuation of a spectrum with Chiari 2 malformation representing a severe version of Chiari 1 malformation, these malformations represent distinct disease processes with overlapping radiographic findings. (see Image. Chiari Malformation Types 1 and 2). Chiari 2 malformation can be associated with numerous additional findings, most commonly hydrocephalus and syringomyelia. Clinically, Chiari 1 malformation can be an asymptomatic hindbrain hernia, while Chiari types 2, 3, and 4 are congenital and clinically significant. Chiari 2 malformation may present a variety of clinical manifestations, which can include spinal symptoms secondary to myelomeningocele, tethered cord syndrome or syringomyelia, symptoms of secondary hydrocephalus, brainstem symptoms, or those due to lower cranial nerve dysfunction. The nosographic collocation of type 0 or 0.5 Chiari malformation or Chiari-like symptoms without tonsillar herniation, type 1.5 Chiari malformation between types 1 and 2, and complex Chiari is controversial and not universally accepted.[3]

Table. Chiari Malformation Types

| Chiari Type |

Features |

| Chiari 0 |

- Syrinx is present.

- No identifiable cause may be found.

- Does not respond to posterior fossa decompression.

- No tonsillar descent noted.

|

| Chiari 0.5 |

- A horizontal line is drawn at the level of the foramen magnum through the middle of the caudal medulla.

- There is ventrolateral herniation of cerebellar tonsils anterior to this line.

|

| Chiari 1 |

- Caudal descent by >5 mm of the cerebellar tonsils below the basion-opisthion line (ie, McRae's line) is observed.

- Associated with syringomyelia, the dilation of the spinal cord central canal with a diameter of ≥3 mm in 12% and 80% of patients.

- Hydrocephalus may be present in up to 10% of patients with Chiari 1 malformation.

|

| Chiari 1.5 |

- Caudal descent of the cerebellar tonsils below McRae's line

- Associated descent of the brainstem with obex

|

| Chiari 2 (Arnold-Chiari malformation) |

- Descent of the cerebellar vermis and brainstem into the upper cervical canal

- Always associated with myelomeningocele

|

| Chiari 3 |

- Cerebellar herniation into a posterior defect of the bifid upper cervical spine resulting in an encephalocele

- Caudal descent of the medulla

|

| Chiari 3.5 |

- Rarely occurs

- Associated with multiple congenital abnormalities

- Absence of cervical vertebrae

- Dura mater does not extend into the spinal canal

- A fistulous tract is present between the fourth ventricle and the esophagus.

|

| Chiari 4 |

- Primarily characterized by cerebellar hypoplasia

- This malformation type may be associated with an occipital encephalocele.

|

Etiology

The precise etiology of Chiari 2 malformation is not entirely understood, with multiple proposed theories over the years. The most recent and accepted theory is the "unified theory," which assumes that the neural tube defect is the etiology from which the cranial features follow.[4] Earlier theories based on tethering of the spinal cord by the myelomeningocele resulting in caudal traction on the hindbrain and brainstem structures have fallen out of favor.

Epidemiology

Chiari 2 malformations are relatively rare, with no large-scale study accurately estimating their incidence. Experts have estimated that the incidence of Chiari 2 malformation occurs in 0.44 of 1,000 births without a gender predominance.[5] Given its association with myelomeningocele, perinatal folate supplementation can decrease its incidence.[6]

Pathophysiology

The current best evidence for the pathophysiology of Chiari 2 malformation is the development of a pressure gradient across the foramen magnum, creating a craniospinal pressure gradient that will cause or hasten the development of a hindbrain hernia. The unified theory assumes that the neural tube defect occurs first, followed by all other manifestations.[4] Ultimately, multiple abnormalities ensue because the lack of mechanical support that the typically distended primitive ventricles provide prohibits normal development of the brain and overlying skull.

History and Physical

Chiari 2 malformation may present a variety of clinical manifestations, which can include spinal symptoms secondary to myelomeningocele, tethered cord syndrome or syringomyelia, symptoms of secondary hydrocephalus, brainstem symptoms, or those due to lower cranial nerve dysfunction. Clinical findings related to the Chiari 2 malformation are often due to brainstem and lower cranial nerve dysfunction. The age of symptom onset is rare in adulthood. The clinical presentation in neonates also differs from that of the older child, who is more likely to experience insidious, rarely severe symptom onset.[7] The symptomatic neonate with Chiari 2 malformation is more likely to develop rapid neurologic deterioration over several days with profound brainstem dysfunction.[7] Other associated clinical findings may include:

- Facial weakness

- Weak or absent cry

- Nystagmus, especially downbeat nystagmus

- Opisthotonos

- Aspiration

- Arm weakness that may progress to quadriparesis [8]

- Apneic spells due to impaired ventilatory drive

- Transient stridor that may progress to respiratory arrest secondary to vagal nerve paresis

- Swallowing difficulties and decreased gag reflex that may manifest as poor feeding, prolonged feeding, nasal regurgitation, cyanosis during feeding, and pooling of oral secretions [7][9]

Symptoms related to syringomyelia, if present, are often associated with the involved spinal cord level, size, and location of the syrinx. Syringomyelia classically presents with dissociated sensory loss (ie, preserved light touch and proprioception with loss of pain and temperature sensation), variable pain involvement, autonomic symptoms, sensorimotor dysfunction, Lhermitte phenomenon, neurogenic arthropathy, and musculoskeletal abnormalities. Scoliosis may present in associated with syringomyelia secondary to lateralized anterior horn compression manifesting as inequality of paravertebral muscle strength. Patients with scoliosis secondary to underlying syringomyelia often present at a young age with an atypical curve, rapid curve progression, and back pain symptoms.

Evaluation

Diagnostic Imaging Studies

When evaluating a patient with Chiari 2 malformation, the diagnosis is primarily based on the neuroanatomy seen with imaging studies. Neuroimaging with magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) provides the highest resolution in evaluating patients with Chiari 2 malformation. For patients who cannot tolerate an MRI, a computed tomography (CT) can also aid in diagnosing Chiari 2 malformation and provide further detail on osseous anatomy. However, the disadvantages of CT include lower resolution, posterior fossa artifact, and ionizing radiation to the child. If fetal ventriculomegaly is present, Chiari 2 malformation can be detected with fetal ultrasound in some cases. In addition to the characteristic features of cerebellar vermis, brainstem, and fourth ventricle caudal displacement, the following findings may also be present:

- Lemon sign: describes the frontal bone indentation depicting a lemon

- Banana cerebellum sign: describes the cerebellum wrapping around the brain stem

- Beaking of tectum

- Absence of the septum pellucidum with an enlarged interthalamic adhesion

- Hydrocephalus

- Syringomyelia

- Craniolacunia of the skull (ie, Luckenschadel) [10]

- Skeletal abnormalities (eg, platybasia, basilar impression, and Klippel-Feil deformity)

- Microgyria

- Heterotopias

- Myelomeningocele

- Tethered cord syndrome

- Agenesis or dysgenesis of the corpus callosum [11][12]

Overall, diagnosing Chiari 2 malformation requires careful evaluation if there is evidence of spinal myelomeningocele. MRI can help diagnose Chiari 2 malformation by showing a downward displacement of the medulla and cerebellum vermis, among other possible findings described above. In this particular patient population, hydrocephalus or shunt failure should be suspected as the etiology of presenting symptoms first and foremost; these should be excluded before attributing symptoms to a syrinx, tethered cord syndrome, or Chiari 2 pathology.

Ancillary Diagnostic Studies

Other ancillary studies that may be considered in addition to diagnostic imaging include:

-

Sleep studies: Involves sleeping overnight in a room where they can monitor breathing, snoring, oxygenation, and seizure activity to identify evidence of sleep apnea.

-

Swallow studies: Fluoroscopy is used to demonstrate cricopharyngeal achalasia.

-

Laryngoscopy: This study can visually verify the movement and function of the vocal cords.[13][14][15]

Treatment / Management

Managing Chiari 2 malformation depends on the extent of the craniospinal malformation and associated neurological impairments. The natural history of patients with Chiari 2 malformation is quite serious, with medullary symptoms remaining the leading cause of death. Surgical intervention is often required to repair associated open neural tube defects and provide cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) diversion of hydrocephalus, typically via shunting. Early suboccipital hindbrain decompression surgery is accepted in an infant or child with symptoms found to be directly related to Chiari 2 malformation. However, there remain few studies exploring the role of decompressive surgery in this patient population, creating ongoing controversy. Those arguing against surgery propose that many of the neurologic findings may be due to intrinsic abnormalities for which surgical intervention cannot improve.[16][17] Proponents of expeditious brainstem decompression argue that the histologic lesions are due to chronic brainstem compression and concomitant ischemia and that surgery should be carried out if the warning signs of stridor, apneic spells, or neurogenic dysphagia are present.[7][18]

Clinicians should consider excluding viral etiologies before attributing the presence or acute worsening of stridor and apnea to the Chiari 2 malformation. Certain medical problems, including neonatal feeding difficulties, apnea, respiratory failure, and neurogenic bowel, may require medical or surgical management.[19]

Surgical intervention to repair myelomeningocele is commonly required. Some evidence has demonstrated the benefits of performing the myelomeningocele repair on the in-utero fetus.[20] For infants with a myelomeningocele diagnosis who did not have a fetal intervention performed, delivery should ideally occur in a hospital with a level III neonatal ICU. Initial management following the delivery includes providing prophylactic antibiotics and covering the lesion. Within the first 72 hours, the open neural tube defect should be repaired surgically.[21] Following surgery, the patient requires close evaluation for the development of hydrocephalus.[22] Serial evaluation for abnormal neurological function is necessary throughout life. Nearly all patients with myelomeningocele will have a neurogenic bladder. This typically requires intermittent catheterization to decrease the risk of renal disease. Notably, a change in function may suggest an acute neurological complication.[23]

Hydrocephalus is a common problem encountered in the management of Chiari 2 malformation. Neuroimaging findings and the severity of symptoms primarily determine the timing and need for surgical intervention in patients. Urgent surgical intervention is required in patients with rapidly progressive hydrocephalus. Another important indication for surgery is if a patient is symptomatic and has hydrocephalus. Some symptoms include vomiting, developmental delays, headaches, focal neurologic deficits, and papilledema. An additional indication includes progressive ventriculomegaly and clear evidence of an obvious obstruction on imaging. The clinician should be mindful that in patients with Chiari 2 malformation, ventricular size may not change in the setting of shunt malfunction.[24] The most common surgical intervention is the placement of a shunt. CSF diversion by shunting prevents CSF from accumulating and increasing intracranial pressure, which can ultimately be fatal.

Differential Diagnosis

The treating clinician should know that presenting signs and symptoms may be associated with myelomeningocele, syringomyelia, scoliosis, and hydrocephalus or shunt failure. The differential diagnoses for Chiari 2 malformation also includes the following:

- Fourth ventricle ependymoma

- Lhermitte-Duclos disease

- Rhombencephalosynapsis

- Other Chiari malformation types

Prognosis

The prognosis of Chiari 2 malformation is variable, dependent on the extent of the malformations and the patient's symptoms. The mortality rate is 71% in infants with vocal cord paralysis, arm weakness, or cardiopulmonary arrest within 2 weeks of presentation, in comparison to patients with a more gradual deterioration who had a 23% mortality.[7] Bilateral vocal cord paralysis is a poor prognosticator for response to suboccipital decompression surgery.[7] In patients requiring suboccipital hindbrain decompression, 68% had a complete or near-complete resolution in symptoms, 20% had no improvement, and 12% had mild to moderate residual deficits.[7]

Complications

In a published series on patients with Chiari 2 malformation who underwent suboccipital hindbrain decompression surgery, respiratory arrest was the most common cause of mortality in 8 out of 17 patients who died, followed by meningitis or ventriculitis in 6 patients, aspiration in 2 patients, and biliary atresia in 1 patient.[9] There was a 37.8% mortality rate in patients who underwent surgery, with follow-up ranging as far out as 6 years.[9]

Deterrence and Patient Education

Chiari 2 malformation, or Arnold-Chiari malformation, is usually associated with spina bifida and is characterized by caudal displacement of the cerebellar vermis, brainstem, and fourth ventricle.[1] Most patients with myelomeningocele also have Chiari 2 malformation in addition to hydrocephalus. Diagnosis of Chiari 2 malformation is primarily made radiographically by MRI. The treatment is typically centered upon a surgical intervention but is complex because of the variability of the malformation and associated clinical presentation. The prognosis of Chiari 2 malformation is dependent upon the extent of craniospinal malformation. While nothing can be done to prevent congenital Chiari 2 malformation, patient education plays a significant role in familiarising the patient's family with the signs and symptoms of the condition and helping to manage expectations. Patient education and counseling regarding conservative and surgical management strategies are also critical in the shared decision-making process.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Chiari 2 malformation is best managed using an interprofessional team that includes primary care clinicians, neurosurgeons, radiologists, urologists, orthopedic surgeons, and occasionally otolaryngologists. Trained nurses, physical therapists, and pharmacists should also assist in caring for patients with Chiari 2 malformation. The patients typically present early in their clinical course because of the associated abnormalities, including myelomeningocele. Utilizing clinical and radiographic findings, the diagnosis can be made. Treatment of Chiari 2 malformation often requires intervention from neurosurgery. Attention must also be given to neonatal feeding difficulties, apnea, respiratory failure, and neurogenic bowel. Rehabilitation is essential to regain mobility and function if there is residual impairment, as well as long-term follow-up to monitor for worsening symptoms. Open communication among interprofessional team members is indispensable for improving outcomes.