Introduction

Primary Support

The muscles of the pelvic floor and the connective tissue of the pelvis, including pelvic fascia, provide stability to the pelvic floor and are essential for the support of pelvic viscera. The visceral layer of pelvic fascia and parametrium becomes condensed around the uterus to form primary support of the uterus in the form of true ligaments; these include:

- Anteriorly: Pubocervical ligament

- Laterally: Cardinal ligament

- Posteriorly: Uterosacral ligament

- Round ligament

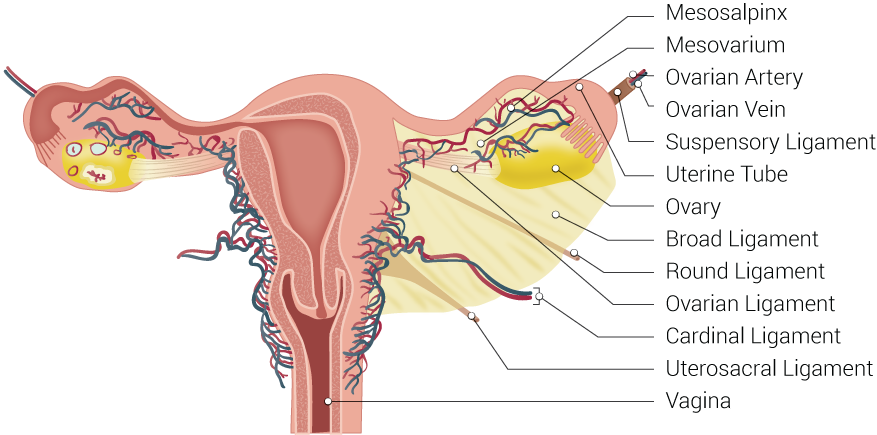

The cardinal ligament and the uterosacral ligaments provide apical support for the uterus and upper vagina (see Image. Uterine Tubal Anatomy and Ligaments).[1] The cardinal ligament is a paired thickening of the parametrium and pelvic fascia at the base of the broad ligament, which extends between the cervix and vaginal fornix medially to the sidewall of the pelvis laterally. It is composed of loose areolar connective tissue surrounded by blood vessels, nerves, and lymphatics.[2] As per Terminologia Anatomica, the cardinal ligament has the name parametrium or paracervix; however, it is also referred to as Mackenrodt ligament, transverse cervical ligament, lateral cervical ligament, paracervical ligament, retinaculum uteri sustentaculum of Bonny or the web are the other terms also used for it.[3]

Secondary Support

Peritoneal folds related to the uterus form less important secondary support of the uterus in the form of peritoneal ligaments; these include:

- Anteriorly: Uterovesical fold (anterior ligament)

- Posteriorly: Rectouterine fold (posterior ligament)

- Laterally: Broad ligament

Structure and Function

Macroscopic Structure

The cardinal ligament is the bilateral fan-shaped condensation of the parametrium and endopelvic fascia at the base of the broad ligament with the following attachments:

- Medial (proximal) attachment: Lateral wall of the cervix and lower vagina [4][5]

- Lateral (distal) attachment: Lateral pelvic wall near the internal iliac vessel origin [4][5]

- Caudal attachment: With the superior fascia of the levator ani muscle [6]

- Cranial attachment: Broad ligament of the uterus [6]

- Posteriorly: Confluent with the attachment of the uterosacral ligament forming cardinal-uterosacral confluence (CUSC). [6]

From its medial attachment, it runs posterolateral; near the pelvic wall, it spreads out in a fan-shaped manner in the transverse plane.

Sections

The total average length of the cardinal ligament is around 10 cm, which is divisible into 3 sections.

- Distal (cervical) section: This is the most medial section, which is attached to the cervix & vagina. Posteriorly, this part is confluent with the uterosacral ligament to form the CUSC. CUSC is very important for vaginal vault support. The absence of significant neural or vascular structures makes this section suitable for surgical use. Its average length is 2.1 cm, and its average thickness is 2.0 cm.[6]

- Intermediate section: This section is related to the ureter. The ureter in this section is crossed superiorly by the uterine artery and vein, and the deep uterine vein may separate the ureter from the neural structures of the dorsal portion, so this section is not disturbed in surgery for pelvic organ prolapse. Its average length is 3.4 cm, and its average thickness is 1.8 cm.[6]

- Proximal (pelvic) section: This is the lateral most and thickest section, which is triangular on a cross-section. It is attached to the pelvic sidewall with an apex at the first branch of the internal iliac artery. Its average length is 4.6 cm, and the maximum average width is 2.1 cm.[6]

According to Tauchi, the cardinal ligament divides in a Y-shaped manner at about the middle of the proximal and distal attachments into 2 parts (branches).[7] One branch, which is composed of nerve fibers and the veins returning from the post-lateral wall of the bladder, is the vesical branch of the cardinal ligament, and the other branch, which is composed of nerve fibers and the veins returning from the uterine cervix, is the cervical branch of the cardinal ligament).

Subdivisions and Contents

The cardinal ligament is divisible into 2 parts: the cranial or superficial vascular part, which chiefly contains vessels, and the caudal or deep neural part, which contains inferior hypogastric plexus nerves.[8][9][10] The passage of the ureter in the intermediate section divides the cardinal ligament into two parts. Tissues that are situated and cross cranially over the ureter are categorized with the parametrium, and the tissues that are situated and cross underneath the ureter are categorized along with the paracervix. The former was considered to correspond to the cranial portion of the cardinal ligament, whereas the latter was considered to correspond to the caudal portion of the cardinal ligament.[4]

- Vascular part (the cranial portion of cardinal ligament, parametrium): An extension of the perivascular sheath of internal iliac vessel branches going to the genital tract that contains:

- Internal iliac artery

- Uterine artery and vein

- Vaginal artery

- Vesical artery

- Smooth muscle

- Connective tissue

- Lymph nodes

- Adipose tissue [4]

- Neural part (the caudal portion of cardinal ligament, paracervix): An extension of the inferior hypogastric plexus that contains:

- Autonomous nerve fibers

- Hypogastric nerve

- Extensions of the inferior hypogastric plexus (pelvic plexus)

- Vessels [4]

Microscopic Structure

According to Range et al., microscopically, the cardinal ligament is chiefly made up of blood vessels (mainly veins), nerves originating from the inferior hypogastric plexus, lymphatic vessels, and the surrounding loose areolar connective tissue.[2] It contains a network of collagen fibers and a few isolated elastic fibers with numerous cellular elements, particularly fibroblasts. They determined that it was not a ligament in the sense of a separate thickening of connective tissue. The cardinal ligaments of women with a prolapsed uterus showed a higher expression of collagen III and tenascin and lower quantities of elastin.[11] Altered connective tissue distribution in the cardinal ligaments with fewer and thinner collagen fibers has been reported in women with prolapse of the pelvic organ.[12]

Functions

In the standing position, the cardinal ligament has a vertical orientation, while the uterosacral ligaments are dorsally oriented, and together they provide apical support for the uterus and vagina.[13] It gives hammock-like support to the uterus that holds the cervix in position and prevents its downward displacement through the vagina.

Embryology

The lateral cervical ligament appears during the tenth week of intrauterine life.[14]

Surgical Considerations

The cardinal ligament is one of the pedicles the surgeon must secure during a hysterectomy. Due to the absence of basic neurovascular structure, the first pedicle of transvaginal hysterectomy involves a distal section of the cardinal ligament along with the CUSC. The presence of ureter and other neural and vascular structures make the intermediate section unsuitable for surgical use.[6] During a vaginal hysterectomy, the traction and cutting of the cardinal ligaments leads to the movement of the ureter out of the operative field. This action guards the ureter against possible iatrogenic injury.[5] After a hysterectomy, suspension of the vaginal vault to the CUSC provides surgical support of the vaginal vault and may reduce the chances of pelvic prolapse.[15]

Clinical Significance

Lymphatic vessels and lymph nodes in cardinal ligaments may be involved in cervical cancer, even up to the most lateral region near the pelvic sidewall. Therefore, in this condition, extensive resection of the cardinal ligament is a must to ensure a disease-free state.[16]