Continuing Education Activity

Atrial fibrillation is the most common type of cardiac arrhythmia. It is the leading cardiac cause of stroke. Risk factors for atrial fibrillation include advanced age, high blood pressure, underlying heart and lung disease, congenital heart disease, and increased alcohol consumption. Although atrial fibrillation may be a permanent disease, various treatments, and risk modifying strategies have been developed to help reduce the risk of stroke in patients that remain in atrial fibrillation. Treatments include anticoagulation, rate control medication, rhythm control medication, cardioversion, ablation, and other interventional cardiac procedures. This activity describes the evaluation, diagnosis, and management of atrial fibrillation and highlights the role of team-based interprofessional care for affected patients.

Objectives:

- Identify the etiology of atrial fibrillation.

- Outline the pathophysiology of atrial fibrillation.

- Summarize the treatment and management options available for atrial fibrillation.

- Explain the interprofessional team strategies for improving care coordination and communication regarding the management of patients with atrial fibrillation.

Introduction

Atrial fibrillation is the most common type of cardiac arrhythmia. It is due to abnormal electrical activity within the atria of the heart, causing them to fibrillate. It is characterized as a tachyarrhythmia, which means that the heart rate is often fast. This arrhythmia may be paroxysmal (less than seven days) or persistent (more than seven days). Due to its rhythm irregularity, blood flow through the heart becomes turbulent and has a high chance of forming a thrombus (blood clot), which can ultimately dislodge and cause a stroke. Atrial fibrillation is the leading cardiac cause of stroke. Risk factors for atrial fibrillation include advanced age, high blood pressure, underlying heart and lung disease, congenital heart disease, and increased alcohol consumption. Symptoms vary from asymptomatic to symptoms such as chest pain, palpitations, fast heart rate, shortness of breath, nausea, dizziness, diaphoresis (severe sweating), and generalized fatigue. Although atrial fibrillation may be a permanent disease, various treatments, and risk modifying strategies have been developed to help reduce the risk of stroke in patients that remain in atrial fibrillation. Treatments include anticoagulation, rate control medication, rhythm control medication, cardioversion, ablation, and other interventional cardiac procedures. [1][2][3]

Etiology

There are many causes of atrial fibrillation (AF), but it shares a strong association with other cardiovascular diseases. The commonly encountered causes include:

- Advanced age

- Congenital heart disease

- Underlying heart disease - valvular disease, coronary artery disease, structural heart disease, atrial ischemia

- Increased alcohol consumption

- Hypertension - systemic or pulmonary

- Endocrine disorders - diabetes, pheochromocytoma, and hyperthyroidism

- Genetic factors

- Neurologic disorders - subarachnoid hemorrhage or stroke

- Hemodynamic stress - mitral or tricuspid valve disease, left ventricular dysfunction, pulmonary embolism

- Obstructive sleep apnea

- Inflammation - myocarditis and pericarditis

Any condition that leads to inflammation, stress, damage, or ischemia affecting the anatomy of the heart can result in the development of atrial fibrillation. In some cases, the cause is iatrogenic.[4]

Atrial fibrillation is referred to as recurrent when a patient has two or more episodes. The three patterns of atrial fibrillation include:

Paroxysmal AF: If recurrent AF reverts spontaneously, it is called paroxysmal AF. Here, the episodes terminate spontaneously within seven days. In younger patients, paroxysmal AF has been commonly found to be secondary to electrically active foci within the pulmonary veins. Elimination of these foci is found to be effective in treating this type of AF since it eliminates the trigger for such episodes.

Persistent AF: If recurrent AF persists, needing either pharmacological or electrical cardioversion, it is called persistent AF. In this case, the episodes last more than seven days, and if it is associated with a rapid and uncontrolled ventricular rate, it may lead to electrical remodeling in the cardiac myocytes causing dilated cardiomyopathy. This type of AF may present as the first episode or as a result of recurrent episodes of paroxysmal AF.

Long-standing persistent AF: AF that has been present for more than 12 months, either due to the failure of initiation of pharmacological intervention or failure of cardioversion.

Permanent AF: It is the type where a decision has been made to abort all therapies because the rhythm is unresponsive.

Epidemiology

Atrial fibrillation is the most commonly encountered cardiac rhythm disorder. The prevalence of atrial fibrillation has been increasing worldwide. It is known that the prevalence of atrial fibrillation generally increases with age. It has been estimated that the number of individuals with atrial fibrillation will double or triple by the year 2050. Although the worldwide prevalence of atrial fibrillation is approximately 1%, it is found in approximately 9% of individuals over the age of 75. At the age of 80, the lifetime risk of developing atrial fibrillation jumps to 22%. In addition, atrial fibrillation has more commonly been associated with males and is seen more often in whites as compared to blacks.[5][6]

Pathophysiology

There are a wide variety of pathophysiological mechanisms that play a role in the development of atrial fibrillation (AF); however, it is cardiac remodeling that accounts for most of them. Cardiac remodeling, particularly of atria, results in structural and electrical changes that eventually become the cause of deranged rhythm in AF. Structural remodeling is caused by the changes in myocytes and the extracellular matrix, and fibrous tissue deposition also plays a major role in some etiologies. On the other hand, tachycardia and shortening of the refractory period lead to electrical remodeling.

Most commonly, hypertension, structural, valvular, and ischemic heart disease illicit the paroxysmal and persistent forms of atrial fibrillation, but the underlying pathophysiology is not well understood. Some research has shown evidence of genetic causes of atrial fibrillation involving chromosome 10 (10q22-q24) that consists of a mutation in the gene alpha-subunit of the cardiac Ik5, which is responsible for pore formation. This is a gain of function mutation, allowing for more pores, increasing the activity within the ion channels of the heart, and thus affecting the stability of the membrane and reducing its refractory time. [1]

Most cases of atrial fibrillation are non-genetic and relate to underlying cardiovascular disease. Typically, an initiating trigger excites an ectopic focus in the atria, most commonly around the area of the pulmonary veins, and allows for an unsynchronized firing of electrical impulses leading to fibrillation of the atria. These impulses are irregular, and pulse rates can vary tremendously. Overall, atrial fibrillation leads to a turbulent and abnormal flow of blood through the heart chamber, decreasing the heart's effectiveness in pumping blood while increasing the likelihood of thrombus formation within the atria, most commonly the left atrial appendage.

Triggers for AF include:

- Atrial ischemia

- Inflammation

- Alcohol and illicit drug use

- Hemodynamic stress

- Neurological and endocrine disorders

- Advanced age

- Genetic factors

History and Physical

History and physical exam are crucial for diagnosing and risk stratifying patients with atrial fibrillation. The presentation of AF can range from asymptomatic to devastating complications such as cardiogenic shock and ischemic stroke. A complete history should focus on symptoms such as palpitations, chest pain, shortness of breath, increased lower extremity swelling, dyspnea on exertion, and dizziness. In addition, history is imperative in identifying risk factors such as hypertension, history of valvular, structural, or ischemic heart disease, obstructive sleep apnea, obesity hypoventilation syndrome, smoking, alcohol intake, illicit drug use, history of rheumatic fever/heart disease, history of pericarditis, and hyperlipidemia. Initial evaluation of any patient presenting with features of AF should include the assessment for hemodynamic instability. Assessment of patients with existing AF includes questions regarding:

- Duration and frequency of symptoms

- History of triggers

- Previously successful modes of termination

- The use of anti-arrhythmic drugs

- Antecedent cardiac diseases

A physical exam should always begin with the assessment of airway breathing and circulation as it is going to affect the decision-making regarding management. On general physical examination, patients may be tachycardic with an irregularly irregular pulse. The heart rate usually ranges from 110/min to 140/min. Extremities should be evaluated for edema, peripheral pulses in both upper and lower extremities, and integumentary signs of peripheral vascular disease (PVD), such as hair loss and skin breakdown.

The physical exam should focus on identifying the cause of AF. For instance, examining the neck of the patient may give some clues regarding carotid artery disease or thyroid problems. The pulmonary examination may reveal signs of heart failure in the form of rales, and the presence of wheezing may indicate antecedent pulmonary diseases such as asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). A cardiovascular exam should consist of careful auscultation of all four cardiac posts and palpation of apical impulse, as this would be crucial in diagnosing an underlying valvular pathology. An abdominal exam should consist of palpating the aorta and listening for abdominal bruits. Moreover, hepatomegaly and abdominal distension may indicate heart failure. Subsequently, a careful examination of the central and peripheral nervous system may reveal signs of transient ischemic attack or cerebrovascular accident.

Evaluation

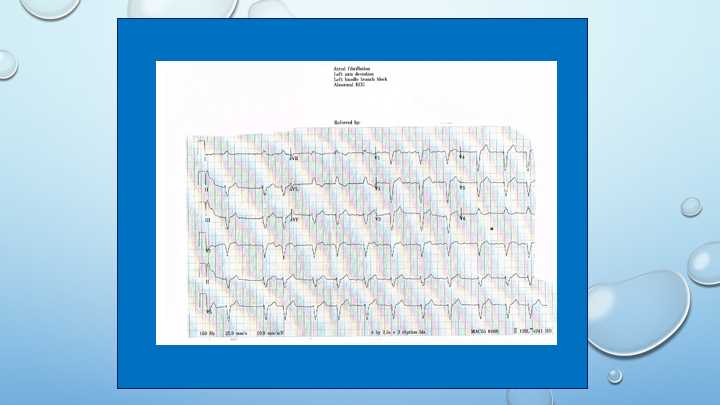

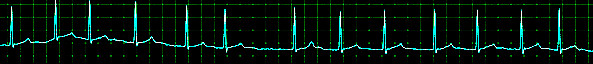

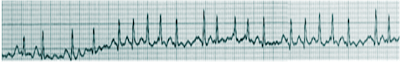

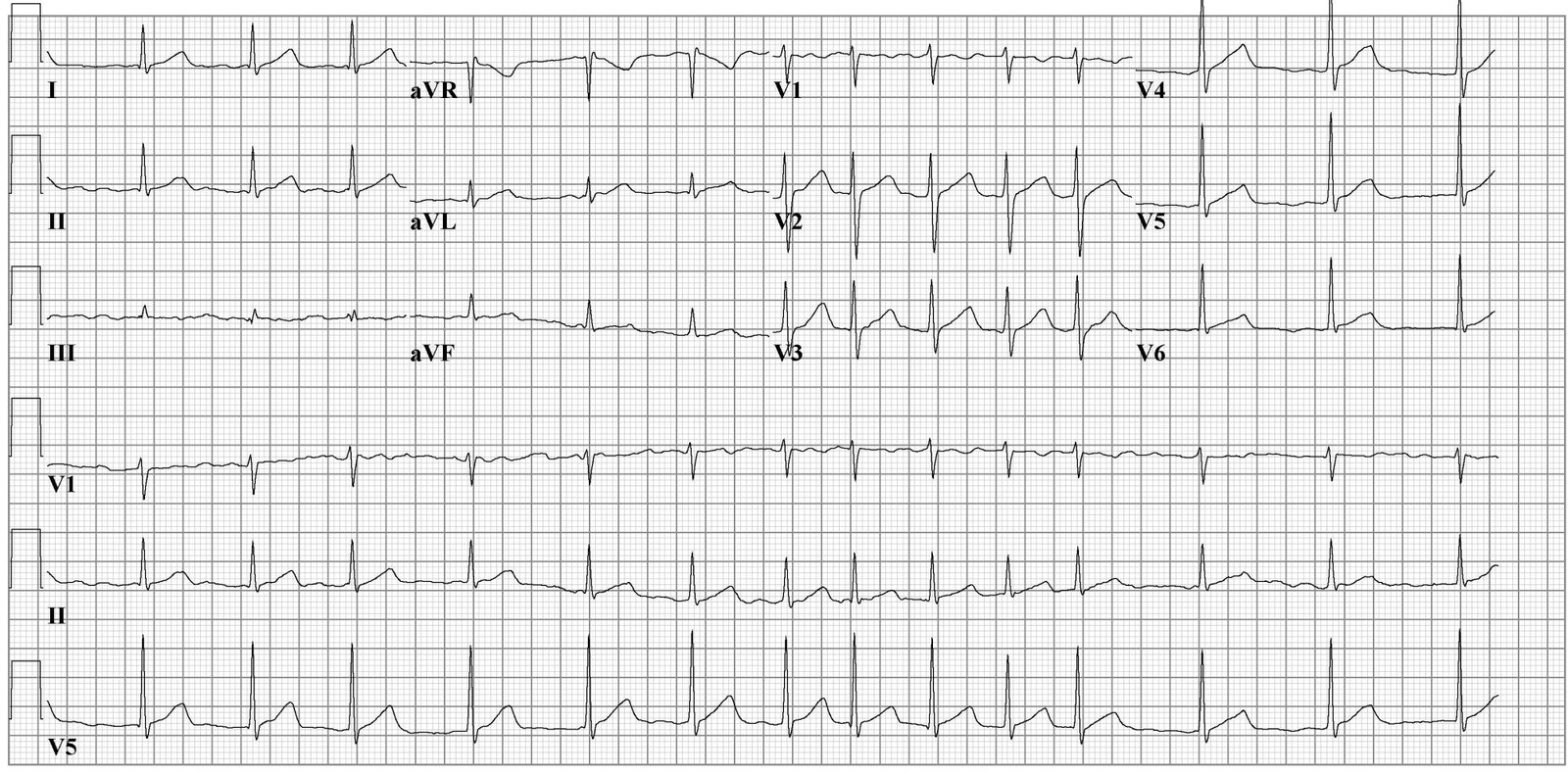

Aside from a detailed history and examination, the ECG is critical in making the diagnosis of atrial fibrillation. On ECG, atrial fibrillation presents with the typical narrow complex "irregularly irregular" pattern with no distinguishable p-waves. Fibrillatory waves may be seen, or they may be absent. The ventricular rate usually ranges between 80 and 180/min.

Laboratory work is required to evaluate for the causes of atrial fibrillation, for example, a complete blood count (CBC) for infection, basic metabolic panel (BMP) for electrolyte abnormalities, thyroid function tests to evaluate for hyperthyroidism, and a chest x-ray to evaluate the thorax for any abnormality.

Several cardiac diseases are associated with AF; therefore, it is essential to send cardiac biomarkers and B-type natriuretic peptide (BNP) to preclude the underlying cardiac disorder. Interventions such as cardiac catheterization may also be needed in certain cases if the history and physical findings are suggestive.

It is imperative to evaluate the patient for pulmonary embolism (with the d-dimers test or spiral CT scan) because the right heart strain can lead to atrial malfunctioning and atrial fibrillation. The patient should be risk-stratified for pulmonary embolism using the PERC and/or Wells criteria. In addition, a transesophageal echocardiogram should be done for these patients to evaluate for atrial thrombus secondary to atrial fibrillation and heart structure. It is important to note that a transesophageal echocardiogram (TEE) should always be done prior to cardioversion in these patients to minimize the risk of stroke.[7][8]

Treatment / Management

The management of atrial fibrillation in the acute setting depends on hemodynamic stability and risk stratification. In cases where the patient is hemodynamically unstable, it is recommended to carry out immediate cardioversion with anticoagulant therapy. Although TEE is recommended before any cardioversion; however, if the patient is hemodynamically unstable due to a rapid ventricular response, cardioversion may be indicated without prior TEE. If there is evidence of rapid ventricular response, a beta-blocker or calcium-channel blocker should be commenced for rate control. These options can be used in the intravenous (IV) form for rapid response. Usually, a bolus is administered to the patient and then started on a drip if symptoms do not resolve. Digoxin can be considered for rate control but is not advised as a first-line agent pertaining to its adverse effects and tolerance. Amiodarone can also be given as a rhythm control agent but is also not a first-line option in the acute setting. In any case, if the decision to start amiodarone is made, cardiology should be consulted before its administration.

In the case of preexisting atrial fibrillation, the patient should be risk-stratified using the CHADs-2-Vasc score, which is helpful in estimating the risk of stroke per year. If the patient receives a 0 score, it is considered "low-risk," and anticoagulation is not recommended in such cases. If the patient receives a score of 1, it falls in the "low-moderate" risk category; the providers should consider anticoagulant or antiplatelet therapy. If the patient receives a score of greater than 2, they are in the "moderate-high" risk category, and anticoagulation therapy is indicated.[2] Rate or rhythm control should also be given to the patient; medications such as beta-blockers, calcium channel blockers, amiodarone, dronedarone, and digoxin are available options. HAS-BLED is also a scoring system that can be used to assess the risk of bleeding for the patient. This is a good indicator of bleeding risk for a patient that is being considered for anticoagulation.

Non-pharmacological therapy includes ablation therapy. Pacemaker placement is considered in severe cases resulting in heart failure in atrial fibrillation.[9][10][11]

Current guidelines

- In patients with AF and elevated CHA2DS2-VASc score of 2 or more, oral anticoagulation is recommended.

- Females with the absence of AF risk factors and males with CHA2DS2-VASc of 1 or 0 have a low stroke risk.

- Non-vitamin K oral anticoagulants (apixaban, dabigatran, edoxaban, and rivaroxaban) are recommended over warfarin, except for patients with moderate to severe MS with a mechanical heart valve in place.

- In all patients with AF, the CHA2DS2-VASc score is recommended to assess stroke risk.

- Obtain renal and liver function before initiating non-vitamin K oral anticoagulants.

- Aspirin is not recommended in patients with low CHA2DS2-VASc scores.

- Idarucizumab is recommended for dabigatran reversal if there is an urgent procedure or bleeding. Andexanet alfa is recommended for the reversal of rivaroxaban and apixaban associated bleeding.

- Percutaneous left atrial appendage occlusion is recommended in AF patients with a risk of stroke who have contraindications to long term anticoagulation.

- If the duration of AF is more than 48 hours or if the time is unknown, start anticoagulation and maintain INR between 2-3 or commence a factor Xa inhibitor for at least three weeks before and at least four weeks after cardioversion.

- Catheter ablation is an option in patients with a low ejection fraction.

- Recommend weight loss in obese patients with AF.

Differential Diagnosis

History and examination play a crucial role in distinguishing various causes of atrial fibrillation. Different presentations on electrocardiography are a cornerstone in establishing the etiology of AF.

Differential diagnoses include:

- Atrial flutter - However, atrial fibrillation has a distinctive irregularly irregular rhythm with absent P-waves, whereas atrial flutter has a regularly irregular rhythm with absent P-waves.

- Atrial tachycardia

- Multifocal atrial tachycardia

- Wolf-Parkinson-White syndrome

- Atrioventricular nodal reentry tachycardia.

Staging

Classification of atrial fibrillation

- Paroxysmal AF is when the episodes terminate spontaneously or with treatment within 7 days. But they may recur with an unpredictable frequency

- Persistent AF is when the AF is continuous and lasts for more than 7 days, and fails to terminate spontaneously.

- Long-standing AF is when the continuous AF lasts more than 12 months

- Permanent is when AF is accepted, and no further treatments are attempted to restore or maintain normal sinus rhythm

- Non-valvular AF occurs in the absence of rheumatic mitral valve disease, mitral valve repair, or a prosthetic heart valve.

CHA2DS2-VASc score

- Heart failure - 1

- Hypertension - 1

- Age more than 75 - 2

- Diabetes - 1

- Stroke, transient ischemic attack- 2

- Peripheral vascular disease - 1

- Age 65-74 - 1

- Female sex - 1

Prognosis

AF is associated with a high risk of thromboembolism and death. Evidence shows that rhythm control does not offer a survival advantage over rate control. Patients with AF have multiple admissions and anticoagulation-related complications over their lifetime. The risk of stroke is ever-present, and the overall quality of life of patients is poor. Finally, the management of atrial fibrillation is prohibitively expensive, with most of the financial burden borne by the patient.

Complications

The major side effect of atrial fibrillation is a stroke. Cerebral vascular accidents (CVA) can lead to severe morbidity and mortality. CVA risk can be reduced significantly by anticoagulation with adjunct rate/rhythm therapy. Other complications include heart disease and heart failure secondary.

Pearls and Other Issues

Atrial fibrillation is a commonly encountered disease that affects many individuals. Advancing age is associated with increased prevalence, with the most catastrophic complication being an acute hemorrhagic stroke. Due to the irregularity of the atria, blood flow through this chamber becomes turbulent, leading to thrombus formation. The most common site for this embolus is the atrial appendage. The thrombus can dislodge and embolize to the brain and other parts of the body. It is essential for the patient to seek medical care immediately if they are experiencing chest pain, palpitations, shortness of breath, severe sweating, or extreme dizziness.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Atrial fibrillation is a chronic disorder that can seriously affect the quality of life and costs healthcare billions of dollars each year. Each year, thousands of patients develop stroke and other embolic phenomena, leading to significant disability. The disorder is best managed by an interprofessional team to improve outcomes.

A nurse should be dedicated to monitoring the anticoagulation profile and ensuring the INR is within the therapeutic range. In addition, the nurse should immediately communicate with the team if there are signs of a stroke or other embolic phenomenon. The nurse has to educate the patient on medication compliance for hypertension and coronary disease and ensure follow-up at regular intervals. Finally, the patient should be educated about the symptoms of a stroke and when to return to the emergency department.[12]

The pharmacist should inform the patient of the different anticoagulants, their benefits, and the adverse risk profile. Besides, the pharmacist should also ensure that the patient is compliant with the medications.

While cardiologists treat the disorder, the role of the pharmacist is critical. Many of these patients are on multiple medications, including antiarrhythmic agents and anticoagulants. In addition, there is some evidence indicating that the use of angiotensin receptor blockers and statins may lower the frequency of atrial fibrillation and increase the probability of successful cardioversion. Thus, the pharmacist has to make sure that the patient's medication doses are therapeutic, there are no drug interactions, and that the patient has therapeutic anticoagulation to prevent a stroke.[12][13][14] [Level 5]

Outcomes

Atrial fibrillation prevalence has been on the rise. The risk of stroke is 5-times higher in a patient with known atrial fibrillation compared to the general public. It is estimated that 19.6% of patients over the age of 65 will have apparent atrial fibrillation by 2030. The most feared side effect of atrial fibrillation is an acute stroke, which can lead to severe morbidity and mortality. It has been shown that 60% of strokes secondary to atrial fibrillation can be avoided with the use of anticoagulants. Using the CHADs-2-VASc score to evaluate patients with atrial fibrillation is a helpful guide for the management of these patients with the ultimate goal of preventing stroke. Proper risk factor stratification and medical/surgical therapy can decrease the risk of stroke and heart failure significantly.[3]