Continuing Education Activity

Trinucleotide repeat disorders are neuropsychiatric disorders caused due to abnormal trinucleotide repeat expansions. Accurate diagnosis, with knowledge of epidemiology and studying ongoing research, is beneficial in the management of these diseases. This activity reviews the clinical presentation, pathophysiology, and upcoming treatment of the five major trinucleotide repeat disorders and highlights the role of the interprofessional team in evaluating and treating patients with this condition.

Objectives:

Summarize the etiology of trinucleotide repeat disorders.

Describe the clinical findings of trinucleotide repeat disorders.

Review the treatments for trinucleotide repeat disorders.

Introduction

Trinucleotide repeat disorders consist of a group of human diseases that are a result of an abnormal expansion of repetitive sequences and primarily affect the nervous system. These occur during various stages of human development.

Repetitive sequences, scattered in the microsatellite regions, usually account for about 30% of the human genome. In a normal person, the main purpose of various lengths of repetitive DNA is to allow for evolutionary plasticity. However, when these repeats extend beyond the code for a viable physiological protein, the expression of this aberrant segment is suppressed. After a certain threshold number, this suppression is lost, and an aberrant protein is coded for, which gives rise to either a functional or a non-functional protein, thereby giving rise to a 'gain of function' or 'loss of function' mutation. With every generation, the number of repeats increases drastically, and the age at which the patient presents is inversely related to the number of expansions. The severity, on the other hand, worsens with every generation due to a larger repeat sequence. Thus, the inheritance pattern of the repeat expansion diseases is evidence of the dynamic nature of these mutations and is termed 'anticipation.'[1]

Myotonic dystrophy (DM), Huntington disease, spinocerebellar ataxia, Friedreich ataxia, and fragile X syndrome fall under the spectrum of trinucleotide repeat disorders.[2]

This article will study the various parameters of trinucleotide repeat disorders by reviewing in detail the five most commonly studied disorders, as listed above.

Etiology

The familial inheritance of trinucleotide repeat disorders is well known. The primary inciting event for this expansion has been studied extensively. Various environmental factors have been postulated to trigger complex cellular responses that trigger cellular mechanisms to increase the chances of cell survival. One effect, in response to cold, heat, hypoxic, and oxidative stresses, is to compromise the fidelity of DNA repair, which unwittingly results in increasing mutagenesis. This occurs in microsatellite regions that are highly mutable and that respond with re-replication in the form of trinucleotide repeat (TNR) expansions.[3]

Epidemiology

The prevalence of trinucleotide repeat disorders can be studied by assessing the distribution of each disorder, specifically.

Friedreich ataxia is the most commonly encountered autosomal recessive ataxia in a clinical setting and accounts for 50% of all cases of hereditary ataxia. The incidence ranges anywhere between 1 in 22,000 to 2 in 100,000, with most studies yielding an incidence among Europeans and North Americans of European descent of approximately 1.5 per 100,000 per year. Overall, the FA carrier rate has been estimated to be between 1 in 60 to 1 in 90, with a disease prevalence of 1 per 29,000.[4]

Studies on a full mutation of Fragile X syndrome in males demonstrate that the number of fragile X cases among Tunisian Jews is 10 times the number in the White population. A lower prevalence of the syndrome is documented among Native Americans due to fewer CGG repeat sequences found among them. Similar results are documented among the Spanish Basque population. Elbaz et al. studied the Afro-Caribbean population, and Crawford et al. examined an African-American population in metropolitan Atlanta, Georgia, USA. Both studies suggested that the point estimate of disease is 1 in 2,500 in their respective general population, which is higher than that observed among Whites.[5][6] The prevalence per studies of full mutations among White males in the general population (∼1 in 4,000) and among females affected with fragile X syndrome is approximately 1 in 8,000 to 1 in 9,000 in the general population.[7]

Spinocerebellar ataxias have a global prevalence of 3 in 100,000, with a wide regional variation. While SCA3 is the commonest subtype around the globe, SCA2 is more prevalent in Cuba than SCA3. SCA7 is the most frequent subtype in Venezuela, and SCA6 is one of the most common autosomal dominant cerebellar ataxias in Northern England. Other similar studies in Germany, the United Kingdom, France, the United States, Japan, and Taiwan confirm the relative rarity of SCA with prevalence rates of 8, 23, 35, 36, and 42 per 100,000. SCA subtypes are each responsible for less than 1% of undiagnosed autosomal dominant cerebellar ataxia (ADCA).[8]

Huntington disease (HD) is an autosomal dominant disorder that results from CAG repeat expansions, usually of paternal origin. The frequency of these expansions was highest in Hispanic Americans and Northern Europeans and lowest in black Africans and East Asians. The prevalence of HD in these populations could be correlated with the frequency of intermediate alleles ('borderline alleles') in the population.[9]

The Myotonic Dystrophy(DM) gene frequency is 1 in 1,100 in a study in the Finnish population, equally divided between DM1 and DM2. A study indicated that DM1 was the most common genetic disease of skeletal muscle in England. A gene frequency of 1 in 7,400 is estimated in the European population. DM1 is very rampant in certain populations. For example, the frequency was 1 in 550 among residents of Northeastern Quebec. The epidemiology of DM1 in the United States has not yielded conclusive results. However, unlike DM1, DM2 does not have a strong bias for intergenerational expansion, and correlations between disease severity and expansion size are relatively weak, which also leads to less anticipation in DM2 than in DM1.[10]

Pathophysiology

The expression of the mutated phenotype depends on several factors. The two most studied factors include the gender of the parent that transmits the repeat and the stage of the development at which the sequence is introduced into the genetic material.

The Concept of Anticipation: There exist different threshold repeat numbers for disease manifestations in both coding and non-coding regions. In an event where the expansion exceeds the threshold, disease manifestation occurs. Additionally, the larger the repeat sequence in the parent, the greater the chances of a phenomenon called anticipation to occur. In this, the larger expansion in the progeny compared to the parent causes disease manifestation to occur earlier and in a more severe manner in the progeny. This vicious cycle continues.

The mechanism of this transmission is explained by the region affected. Trinucleotide repeat disorders were classified as type 1, which are polyglutamate (polyQ) disorders with abnormal CAG repeats in the coding region, and type 2 or non-polyglutamate (non-polyQ) disorders which are triplet expansions in the non-coding regions, by La Spada et al.[11] The five most common disorders are classified and studied as follows-

Non-Coding Region Repeats

- Fragile X syndrome (FXS): This occurs due to CGG repeats in the non-coding region of the fragile X mental retardation 1 (FMR1) gene. The fragile X CGG repeat has four forms: common (6–40 repeats), intermediate (41–60 repeats), premutation (61–200 repeats), and full mutation (>200–230 repeats), occurring almost exclusively through maternal transmission.[7] A large non-coding expansion is thought to be more forgiving when it occurs due to paternal transmission. During sperm formation, large non-coding expansions occur up until the stage of the primary spermatocyte. However, in the subsequent spermatogonia, large deletions in these pathological expansions are observed, a process called contraction, thus reducing the size of the transmitted expansion. Primary germ cells in the females are arrested in the M1 phase and are completed during fertilization. This expansion stays arrested during M1 in the primary oocytes during maternal transmission and is transmitted to the progeny subsequently.

- Myotonic dystrophy type 1 (DM1): The pattern of transmission is very similar to Fragile X syndrome in that it is transmitted maternally and in an X-linked dominant manner. However, the length of the CTG expansion, ergo, the severity of the disease, correlates with the maternal age, suggesting that the expansion occurs in the quiescent M1 phase of the primary oocyte. Paternal transmission in this condition is forgiving as well due to the phenomenon of ‘contraction’ as explained above.

- Spinocerebellar ataxias: This class comprises those SCAs that are caused by DNA repeat expansions falling outside the protein-coding region of the respective disease genes. In other words, the pathogenic expansion does not encode glutamine or any other amino acid in the disease protein. Ataxias included in this category are SCAs 8, 10, and 12, although there is some uncertainty about the pathogenic mechanism in SCA8.[12]

Coding Region Expansion

- Huntington disease (HD): The pathological CAG expansion sequence in Huntington disease is most likely due to paternal transmission. The offspring of maternal transmission is largely normal due to a contraction in CAG repeat expansion size. In males with existing premutation alleles in the germ cells, once the mutation in the coding reaches the threshold, a 3- to 175-fold increase in the number of repeats is favored over contraction.

- Spinocerebellar ataxias (SCA): It is an autosomal dominant transmission that occurs by paternal transmission (up to 28 repeats). The offspring of an affected young mother is likely to show a contraction of the CAG repeats. However, in older mothers, the multiplication of CAG repeats occurs in the arrested primary oocyte. Somatic changes in TNR tract length occur in patients with SCA, but there is little increase in heterogeneity with increasing length.

- Friedreich ataxia (FA): FA is caused by an autosomal recessive disorder involving GAA triplet expansion in the first intron of the FRDA gene on chromosome 9q13 in 97% of patients. The FRDA gene encodes a widely expressed 210-amino acid protein, frataxin, which is located in the mitochondria and is severely reduced in FA patients. A normal individual has 8 to 30 copies of this trinucleotide, while FA patients have as many as 1000. Pathology: The main sites of pathology in FA are the dorsal root ganglia, posterior columns of the spinal cord, corticospinal tracts, and the heart. A gross examination reveals a small spinal cord with the posterior and lateral columns particularly affected. In the posterior columns, demyelination is seen. In particular, the large fibers arising in the dorsal root ganglia, Clarke column, and dentate nucleus are affected. Iron deposits in the myocardium and, consequently, hypokinetic heart failure have been reported.[4]

History and Physical

The presentation of 5 main disorders has been discussed below-

Friedrich Ataxia

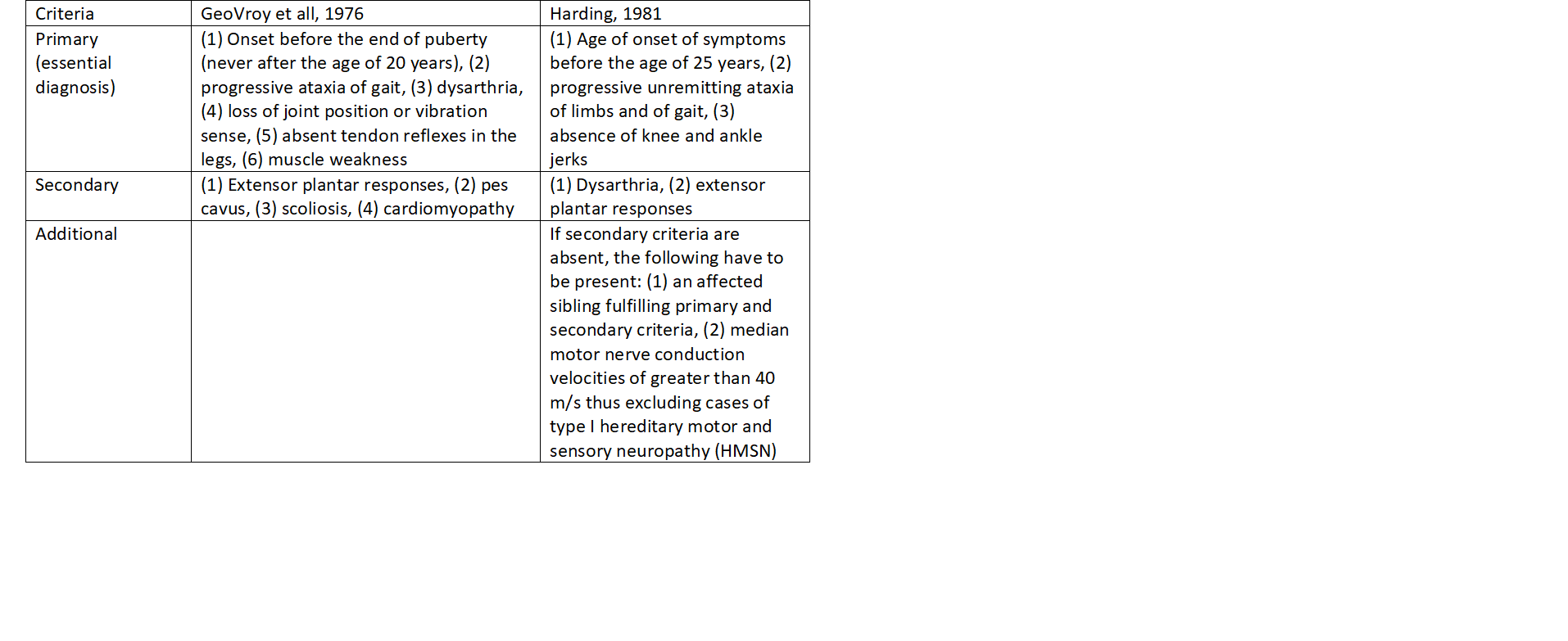

The cardinal clinical features of FA include progressive gait and limb ataxia, absent lower limb reflexes, extensor plantar responses, dysarthria, and reduction in or loss of vibration sense and proprioception (sensory modalities mediated by posterior column neurons). Cardiomyopathy, scoliosis, and foot deformity are common but non-essential features. The use of strict diagnostic criteria (refer table 1) was essential to ensure that patients used to study the natural history of FRDA, as well as for molecular studies, definitely had FRDA. Cases of FRDA meeting these criteria are defined as typical FRDA; those that do not meet the essential criteria are labeled atypical. Nerve conduction studies characteristically show absent sensory nerve action potentials as well as absent spinal somatosensory evoked potentials, although these may be reduced or even normal early in the disease course. Motor nerve conduction velocities are reduced to a lesser extent than sensory nerve action potentials.[4]

Fragile X Syndrome

The facial features are often less noticeable, particularly in affected females and children. The macroorchidism often develops during or after puberty and is frequently absent in young patients. Seizures are observed in approximately 20% of young affected males, with a lower prevalence in adults. Fragile X infants often have relative macrocephaly persisting into adult life. However, the adult height of affected males is below normal. A few patients present with either overweight or general persisting overgrowth, which can be confused with either Prader-Willi syndrome or Sotos syndrome. During infancy, connective tissue abnormalities, such as congenital hip dislocations and inguinal hernia, may be present. In later life, connective tissue dysplasia may lead to scoliosis, flat feet, and mitral valve prolapse.

Syndromic associations like Robin sequence (micrognathia, glossoptosis, and soft cleft palate), the FG syndrome (congenital hypotonia, macrocephaly, distinctive face, and imperforate anus), and the DiGeorge anomaly (defects of the thymus, parathyroids, and great vessels) are reported. However, there is no definite evidence of any association with the FMR1 gene.

Spinocerebellar Ataxias

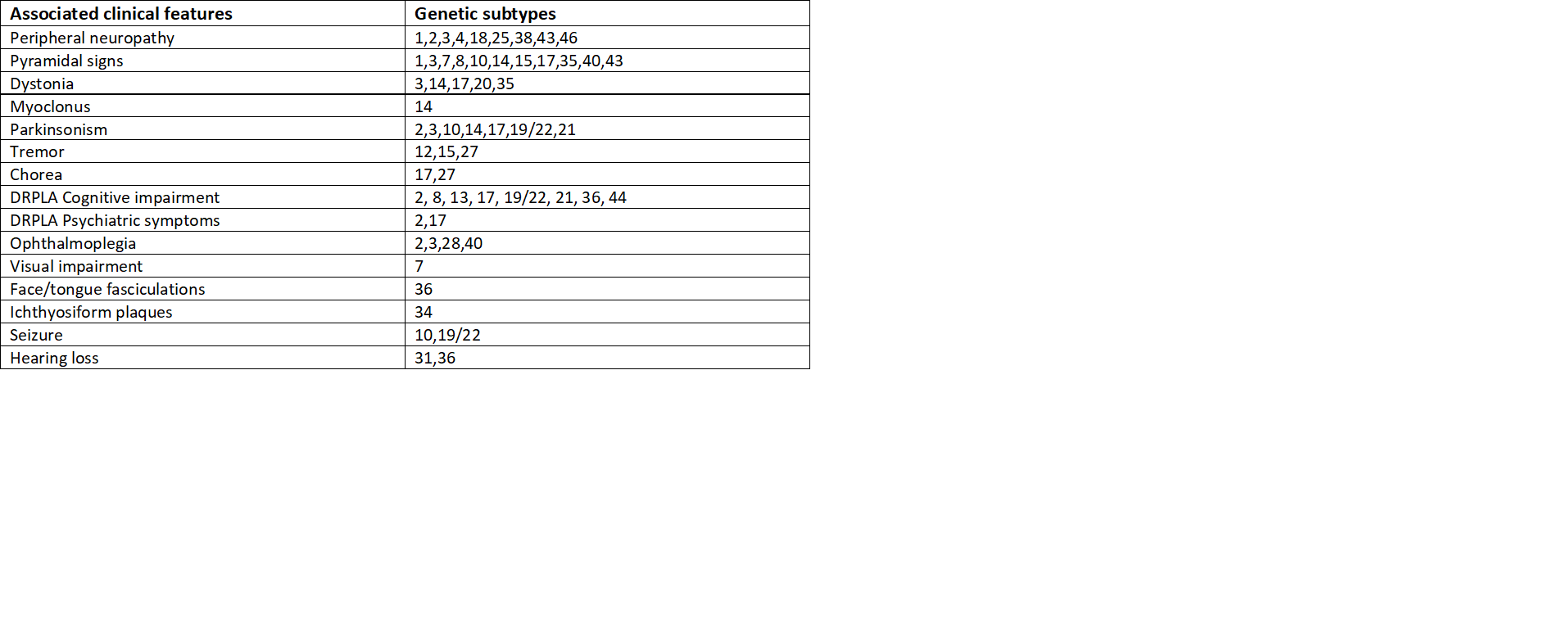

The triad of symptoms of SCA includes gait ataxia and incoordination, nystagmus/visual problems, and dysarthria. Specific features depending on individual SCAs include pyramidal, extrapyramidal signs, ophthalmoplegia, and cognitive impairment. These type-specific additional features help distinguish among subtypes.[8] Refer to the table for further classification based on symptoms (table 2).

Huntington Disease

The classic clinical triad in HD is (1) progressive movement disorder, most commonly chorea; (2) progressive cognitive disturbance culminating in dementia; and (3) various behavioral disturbances that often precede diagnosis and can vary depending on the state of the disease.

- Cognitive disturbance: Subtle cognitive impairment is among the earlier manifestations in the disease process and is associated with progressive caudate atrophy. By the time of diagnosis, most subjects with HD have significant cognitive impairment readily measurable by neuropsychological testing.

- Movement disorder: Although the range of movement disorders in HD extends beyond chorea, it remains the classic motor sign of HD. Overt chorea involving larger muscle groups becomes evident over the course of the disease. Patients often will incorporate chorea into purposeful movements, something known as parakinesia. As this progresses, disabling flailing can manifest in these patients.

- Behavioral disorders: They range from affective illness, most notably depression and apathy, to delusional behavior that can include, rarely, hallucinations. As is true of other progressive neurodegenerative diseases, the behavioral disorders of HD evolve during the course of illness. Most HD gene carriers will experience some behavioral symptoms before establishing the diagnosis.[13]

Myotonic Dystrophy

The clinical presentation has a wide range of severity. It could present as a lethal disorder of infancy or a mildly presenting disease in late adulthood.

Congenital and prenatal presentation: The prenatal manifestations include reduced fetal movement, polyhydramnios, and ultrasound findings of talipes equinovarus or borderline ventriculomegaly. After birth, neonatal hypotonia, along with feeding and respiratory difficulty, are common. It is important to consider the diagnosis of DM1 in these patients even when they have a negative family history because their mothers, who are the source of the mutated gene transmission, might be asymptomatic but carriers of full mutations.

Childhood DM: The onset of DM1 is after the first year but before age 10. Often present with predominant cognitive and behavioral features that are not accompanied by conspicuous muscle disease.

Classical/Adult-onset DM1: This occurs between the second and fourth decades. The most common presenting symptom is myotonia. The myotonia in DM is more pronounced after rest and improves with muscle activity, the "warm-up phenomenon." In contrast to RGM, the action myotonia in DM1 selectively involves specific muscle groups of the forearm, hand, tongue, and jaw. The cardinal finding on examination is myotonic myopathy, consisting of action and percussion myotonia, weakness, and muscle wasting in a characteristic distribution.[10]

Evaluation

Clinical suspicion of a repeat disorder is paramount for a successful diagnosis and should not be determined solely based on positive family history. This implies that any patient showing features suggestive of trinucleotide disorders could still be a 'sporadic case' and should be further evaluated with a genetic test to confirm or exclude the diagnosis.[2]

For genetically isolating the repeat expansion, initially, polymerase chain reaction (PCR) was used. However, multiple shadows observed while sizing these repeats prompted the advent of small pool PCRs, which allowed for precise quantification of the frequency of repeat changes. However, disorders with CGG repeats, even today, are measured using a southern blot. The polymerases have difficulty traversing through long CG-rich tracts, making southern blotting a better diagnostic test. Together these account for 99% of the clinical accuracy.[14]

Treatment / Management

The approved management for trinucleotide repeat disorders is mainly conservative and varies due to the varying presenting features in every disorder. The following is a summary of the treatment:

Friedrich Ataxia

Antioxidants are biological and chemical compounds that reduce oxidative damage. The following are the antioxidants commonly used in patients with Friedrich ataxia- coenzyme Q, vitamin E, high dose ascorbic acid, idebenone, a synthetic coenzyme Q, N-acetylcysteine, selegiline, Dehydroepiandrosterone, Pioglitazone, a peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma (PPARϒ) and induces the expression of enzymes involved in mitochondrial metabolism, including superoxide dismutase, which is an important antioxidant defense in nearly all cells exposed to oxygen.[15]

Fragile X syndrome

Careful medical follow-up and sometimes intervention is required as the physical and behavioral problems of fragile X patients are related to their stage of development.

Neuropsychiatric manifestations: Seizures are observed in approximately 20% of males and 5% of females and necessitate a timely diagnosis and treatment. Influencing behavioral problems is difficult, although behavioral therapy and avoidance of overwhelming stimuli may alleviate some of the symptoms. Some physicians recommend pharmacological intervention for behavioral problems. The need for special education and training, especially in younger children, is of primary importance. Speech therapists and physiotherapists can help with language and motor development.

Connective tissue manifestations: During infancy, associated connective tissue abnormalities may present as congenital hip dislocations and inguinal hernias that need surgical correction. Some children fail to thrive because of gastro-oesophageal reflux, tactile defensiveness, or difficulties in sucking. The latter of these problems requires attention from a specialized speech therapist or physiotherapist, while gastroesophageal reflux can be treated by dietary advice or medication or both.

Other: The frequent otitis media and sinusitis in approximately 50% of affected children require adequate intervention (antibiotics or polyethylene tubes or both). Approximately 30% to 50% of cases need ophthalmological help for strabismus, myopia, or hyperopia.[16]

Spinocerebellar Ataxia

No current FDA-approved treatment exists for SCA. However, gene testing can confirm the diagnosis. Although incurable, establishing a specific diagnosis can put an end to the quest for the etiology, permit a discussion of the prognosis, and facilitate discussions of genetic risk to other family members. The psychological lift of simply putting a name to a previously mysterious disease, even if there is no cure, should not be underestimated for some patients. Further advancements in treatment are currently in the pipeline.[12] A 24-week neuro-rehabilitation program with neuro-rehabilitation therapy, focusing on balance, coordination, and muscle strengthening, has been found to be beneficial for reducing cerebellar symptoms in spinocerebellar ataxia type-2.[17] The relevance of other types of SCA is being studied in detail.

Huntington Chorea

The current management of Huntington's mainly aims at managing each symptom rather than the basic pathogenesis. More recently, however, clinicians have tended first to use newer atypical antipsychotic drugs in persons who experience severe chorea, especially when it is accompanied by psychiatric symptoms warranting antipsychotic use, such as delusions. Depression, which commonly accompanies Huntington's Disease, is treated with newer antidepressants. Thus far, limited trials of cognitive-enhancing agents used primarily in patients with AD, such as memantine, rivastigmine, and donepezil, have shown only modest benefits. Bradykinesia and rigidity in younger-onset individuals can respond to dopaminergic agents used in parkinsonism.[13]

Muscular Dystrophy

The management of DM is based on genetic counseling, preserving function and independence, and preventing complications. In DM1, the combined effects of disordered breathing and weakness of the diaphragm and oropharyngeal muscles often lead to respiratory impairment and nocturnal hypoventilation. It is useful to monitor FVC and FEV1 changes from sitting to a supine position at clinic visits. Many patients will progress to the point of requiring non-invasive nighttime ventilatory support. The placement of a pacemaker or cardiac defibrillator can be lifesaving in DM1. The ECG should be monitored annually.[10]

Differential Diagnosis

Friedreich Ataxia

- Abetalipoproteinemia

- Ataxia with isolated vitamin E deficiency

- Dentatorubropallidoluysian atrophy

- Hereditary motor and sensory neuropathies

- Refsum disease

- Spinocerebellar ataxia (SCA) types 1, 2, 3[18]

Fragile X Syndrome:

- Autism spectrum disorders

- Genetics of Marfan syndrome

- Gigantism and acromegaly

- Pediatric attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD)

- Pervasive developmental disorder

- Prader-Willi syndrome

- Rett syndrome

- Asperger syndrome[19]

Spinocerebellar ataxia:

- Abetalipoproteinemia

- Ataxia with isolated vitamin E deficiency

- Dentatorubropallidoluysian atrophy

- Hereditary motor and sensory neuropathies

- Refsum disease[20]

Huntington Disease

Although HD is a distinctive phenotype, mimickers of HD are encountered occasionally in clinical practice. Many of them can be excluded based on the history or features of the physical examination. When in doubt, molecular testing is used for identifying or excluding HD. These include other

Dominant disorders-

- Polyglutamine diseases

- Dentatorubral-pallidoluysian atrophy (DRPLA)

- SCA17

- Huntington disease-like 2

- Neuroferritinopathy.

Recessive and X-linked disorders that mimic HD include neuroacanthocytosis family of diseases.[13]

Myotonic Dystrophy

Differentials for myotonic dystrophy include

- Recessive generalized myotonia

- Limb-Girdle muscular dystrophy

- Duchenne muscular dystrophy

- Myotonia congenita (Thomsen disease)

- Paramyotonia congenita (Eulenburg disease)[21]

Pertinent Studies and Ongoing Trials

So far, the treatment of trinucleotide repeat disorders has been mainly complication-oriented, with no actual treatment for the disorder itself. The following are the upcoming treatment modalities being studied at length to tackle this.

Limiting Expression of Trinucleotide Repeats

Several promising clinical trials are being conducted to find an effective way of blocking the translation of the aberrant protein. The proposed pharmacological treatment of Trinucleotide repeats targets three fronts of genetic expression- DNA, RNA, and protein.[14]

A common pathogenic mechanism for TRDs is protein or RNA toxicity that creates neuronal dysfunction and death. The therapy aims to lower the expression of this mutated gene by inhibiting the messenger RNA (mRNA) using either antisense oligonucleotide (ASO) or RNA interference (RNAi).

Polyglutamate-related disorders mainly include Huntington's disease and spinocerebellar ataxias. The forefront of research in polyglutamate-related trinucleotide repeat disorder treatment involves a reduction in expression of the target mRNA levels in a non-specific or allele-specific manner. The expression of the target ligand, the mRNA, is inhibited by engaging with therapeutic agents like microRNA (miRNA), also called ASO. The CAG repeat antisense oligonucleotides bind to the CUG repeat RNA and block pathogenic RNA–protein interactions. The release of the expanded CUG transcripts from nuclear foci presumably facilitates their transport to the cytoplasm, where they undergo rapid decay. This reduces the translation and aberrant protein formation and subsequently reduces cytotoxicity.

With regard to DNA, the ongoing research for treatment is to prevent pathological DNA repeat expansion. This can be achieved by inhibiting DNA repair proteins that promote expansion. This is a possible strategy to regulate the repeat length. Research is underway for the same. The challenge would be to preserve normal mutation repair.[22]

Other Pathways Implicated in Limiting Neuronal Loss

These include three major pathways: molecular chaperones, ubiquitin-proteasome degradation, and autophagy. All three pathways have been implicated in polyQ disorders and hence their treatment. The target molecules in each pathway are interrelated. For example, a quality control protein recently shown to modulate polyQ toxicity is the carboxy-terminus of Hsc70 interacting protein (CHIP). CHIP functions both as a co-chaperone and as a ubiquitin ligase, thereby linking the chaperone and proteasome pathways. Numerous molecular chaperones, including Hsp70, Hsp40, and the cytosolic chaperonin TRiC, have been shown to suppress polyQ aggregation and or toxicity in various model systems.[12]

The proposed treatment for Friedrich Ataxia, Apart from Antioxidants

These include-

1. Deferiprone, an iron chelator, is a small molecule that preferentially binds iron and prevents a build-up of reactive oxygen species, thereby reducing oxidative stress.

2. Erythropoietin (EPO) biological functions also include playing an important part in the brain's response to neuronal injury and in the wound healing process.

3. Histone deacetylase inhibitors (HDACis) modulate the level of acetylation of chromosomal proteins and other cellular targets and can revert the silent heterochromatin to an active chromatin conformation and restore the normal function of the silenced gene.

4. Interferon-gamma 1b has been found to increase frataxin expression in dorsal root ganglion neurons in treated mouse models, and these models also had improved sensorimotor performance.[15]

Treatment for Normal Aging in Patients with FXS

FXAP is a protein required in the normal aging process in all individuals. In patients with FXS, this normal process is hampered. New targeted treatments for FXS, including mGluR5 antagonists, GABA A and B agonists, minocycline, and others, are being studied to that effect.[23]

Stem Cell Therapy

Marrow stromal cells (MSCs) are being studied for treating neurodegenerative trinucleotide repeat disorders that are almost always fatal, in particular, Huntington's disease (HD). They are currently being tested in FDA-approved Phase I to III clinical trials for many disorders since extensive pre-clinical studies for neurodegenerative disorders were found to be promising. The potential benefits arise from the innate trophic support from MSC or from augmented growth factor support, such as delivering brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) or glial-derived neurotrophic factor (GDNF) into the brain to support, decrease free radical damage through their paracrine actions, and promote synaptic connections among the afflicted neurons. This is done by using marrow stromal cells as a mode of delivery for these factors. This ultimately induces the survival and regeneration of host neurons. The current protocols are provided in support of applying MSC-based cellular therapies to the treatment of trinucleotide repeat disorders.[24]

Prognosis

Friedreich's ataxia, when associated with dilated cardiomyopathy, suggests greater morbidity due to the requirement for a transplant. Otherwise, in patients without cardiomyopathy, and just ataxia and diabetes, which, although debilitating, is not lethal.[25]

On the whole, patients with Fragile X syndrome have a near-normal lifespan. The average age of death was about 12 years lower than in the general population for both men and women, but this was likely a bias of ascertainment. The commonest causes of death were cardiovascular, cerebrovascular, and malignant diseases, similar to those in the general population. However, FMRP is a critical protein in aging in all individuals. Those with FXS may suffer from problems with aging because of the lack of FMRP. However, further research is necessary to fully explain the subgroups of patients with FXS susceptible to problems with aging and how they could benefit from treatment.[23]

In patients with spinocerebellar ataxias, total physical dependency is not the norm. Although they are often life-shortening, it is impossible to accurately predict life expectancy due to a great amount of variation in the presentation and severity. In some severe cases, the last stages of their illness will require continuing care by professionals in a facility.[26]

Huntington's disease causes extensive depression that leads to a high suicide rate among these patients, up to four times the rate in the normal population.[27]

Patients with myotonic dystrophy adult-onset have a markedly reduced survival rate from an expected rate of 78% to an observed rate of 18%. A significant weak positive correlation between the CTG repeat length and younger age at death was found. The cause of death most commonly documented was pneumonia and cardiac arrhythmias.[28]

Complications

Most trinucleotide repeat disorders have a wide spectrum of complications, ranging from debilitating physical disabilities like ataxia, chorea, severe muscle weakness, and connective tissue defects to lethal complications like cardiomyopathy, diaphragmatic weakness, severe depression, etc, depending on the kind of repeat disorder. Specific associations include-

Fragile X syndrome: Seizures, otitis media, behavioral disorders, speech disorders.[29]

Friedreich's ataxia: Diabetes mellitus, scoliosis, dilated cardiomyopathy, foot deformity, sensory impairment.[30]

Spinocerebellar ataxia: Fatigue, pain, dysautonomia, REM sleep behavioral disorder.

Huntington disease: Manic-depressive disorder, swallowing difficulties, choking, incontinence.[31]

Myotonic dystrophy: Muscle weakness, myotonia, dysphagia, hyperglycemia, female infertility, male pattern baldness, dysphagia, hypogonadotropic hypogonadism, cataracts, learning disabilities, QT lengthening, AV block, immune deficiency.[32][33]

Deterrence and Patient Education

Patients with trinucleotide repeat disorders are afflicted by this illness for a lifetime. Although the complications of these disorders range from mild to severe, counseling and explaining these shortcomings is important for the complete understanding and acceptance of this condition in both the patient and their family.

Regular psychiatric evaluation and psychological support should be offered to all patients with repeat disorders. Other than depression, which occurs due to the limiting nature of this condition, a variety of psychiatric anomalies are associated with most repeat disorders. Manic-depressive disorders are associated with Huntington disease, and dementia is associated with certain spinocerebellar ataxia (e.g., SCA 2). Friedreich ataxia is linked to MDD, and fragile X syndrome patients can present with anxiety, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, autism, mood instability, and aggression.[34] Personality anomalies were observed in patients with myotonic dystrophy, including hostility, depression, and interpersonal sensitivity.[35][36][37]

Genetic Counselling

Along with an accurate diagnosis, patients with fragile X–related mental retardation, Huntington disease, a variety of inherited ataxias, and myotonic dystrophy should receive an opportunity for genetic counseling and family planning. These disorders are associated with the phenomenon of anticipation, which leads to an earlier and more severe manifestation of the illness in the progeny of the patient. Additionally, the penetrance of these disorders is variable and, in most cases, very high, making it important to educate and inform the patient about the risks in their progeny.

Pearls and Other Issues

Here are some important points:

- Trinucleotide repeat disorders are caused due to an abnormal number of triplet repeat sequences either in the coding or the non-coding regions and are a result of either maternal or paternal transmission.

- Trinucleotide repeat disorders were initially classified as type 1, which are polyglutamate (polyQ) disorders with abnormal CAG repeats in the coding region, and type 2 or non-polyglutamate (non-polyQ) disorders.

- Response to cold, heat, hypoxic, and oxidative stresses have been postulated to trigger complex cellular responses that trigger cellular mechanisms to increase the chances of cell survival. One effect is to relax the fidelity of DNA repair that has been postulated to cause extensive repeat expansions in even otherwise susceptible microsatellite regions.

- The inheritance pattern of the repeat expansion diseases is evidence of the dynamic nature of these mutations and is termed 'anticipation,' which leads to an earlier and more severe presentation of disease in the progeny.

- This also implies that the threshold mutation can occur through anticipation, which could manifest disease in a patient with normal parents, who would harbor a subthreshold mutation.

- The diagnosis of these disorders requires both a strong clinical suspicion, even in the absence of family history, as well as a small-pool PCR.

- Current treatment depends on supportive care and managing complications to improve the quality of life and genetic counseling to educate the patient about the risk of the disease in the progeny. Friedreich's ataxia is treated with high-dose antioxidants that have been proven to have some effect but are not curative.

- Most patients have psychiatric manifestations, and hence psychiatric evaluation and psychological support should be offered to all patients with repeat disorders.

- The upcoming research for the treatment of CGA RELATED trinucleotide repeat disorders therapy aims to lower the expression of this mutated gene by inhibiting the messenger RNA (mRNA) using either antisense oligonucleotide (ASO) or RNA interference (RNAi).

- Molecular chaperones, ubiquitin-proteasome degradation, and autophagy, all three pathways, have been implicated in polyQ disorders and hence in its treatment.

- Innate trophic support from MSC or from augmented growth factor support, such as delivering brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) or glial-derived neurotrophic factor (GDNF), is in the clinical trial phase II/III for treating trinucleotide repeat disorder.

- An interprofessional team that provides a holistic and integrated approach to patients with trinucleotide repeat disorders can help achieve the best possible outcomes since complications of these disorders are not uncommon.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

An interprofessional team that provides a holistic and integrated approach to patients with trinucleotide repeat disorders can help achieve the best possible outcomes. Since complications of these disorders are not uncommon, the importance of an interdisciplinary approach of various disciplines cannot be undermined. Depending on the type of repeat disorder, the personnel involved in management would vary. Largely, the role of psychiatrists, neurologists, physiotherapists, nurse practitioners, occupational therapists, and pharmacists is equally crucial amongst all trinucleotide repeat disorders. While neurologists and psychiatrists diagnose and prescribe the required treatment for these conditions, family education and counseling is a crucial roles of the nurse practitioner as well. Chronic conditions require long-term medication, making the pharmacist a crucial part of this team. Lastly, since most of these disorders are accompanied by physical symptoms that either cause spasms or limiting movement disorders, both occupational therapists and physiotherapists play an important role in improving the quality of life of the patient.[38]

Collaborating, shared decision-making, and communication are key elements for a good outcome. The interprofessional care provided to the patient must use an integrated care pathway combined with an evidence-based approach to planning and evaluation of all joint activities. The earlier signs and symptoms of a complication are identified, the better the prognosis and outcome. [Level 3]