Introduction

Gluconeogenesis refers to a group of metabolic reactions in cytosol and mitochondria to maintain the blood glucose level constant throughout the fasting state. Reactions in the gluconeogenesis pathway are regulated locally and globally (by insulin, glucagon, and cortisol), and some of them are highly exergonic and irreversible.[1] The balance between stimulatory and inhibitory hormones regulates the rate of gluconeogenesis. The liver and, secondarily, the kidney are the organs that supply circulating blood glucose to various tissues. Different tissues have multiple mechanisms to generate glucose during fasting, maintaining adequate energy levels for their proper function.[2]

Fundamentals

Several tissues require continuous glucose supply, including the brain, erythrocytes, renal medulla, the lens and cornea, testes, and skeletal muscles during exercise. The brain uses glucose exclusively in both the fed and fasting states except for prolonged fasting, which uses ketones. Notably, the daily amount of glucose used by the brain accounts for 70% of the total glucose produced by the liver in a normal fasting person.[3]

Initially, during the first hours of fasting, hepatic glycogenolysis is the primary source of glucose. Glucose stored as glycogen can cover the energy needs roughly for one day; the amount of glucose supplied by glycogen reserves is 190 g, while the daily requirements for glucose are 160 g. After several hours of starvation, gluconeogenesis and glycogenolysis contribute equally to blood glucose. The amount of glucose supplied by glycogen decreases rapidly while the increase in the glucose fraction contributed by gluconeogenesis results in keeping constant the total amount of glucose produced. Estimates are that 54% of glucose comes from gluconeogenesis after 14 hours of starvation, and this contribution rises to 64% after 22 hours and up to 84% after 42 hours.[4] However, when glycogen stores deplete, the body uses lactate, glycerol, glucogenic amino acids, and odd chain fatty acids as glucose sources. In prolonged fasting, kidney participation in gluconeogenesis increases and is responsible for about 40% of total gluconeogenesis.[5]

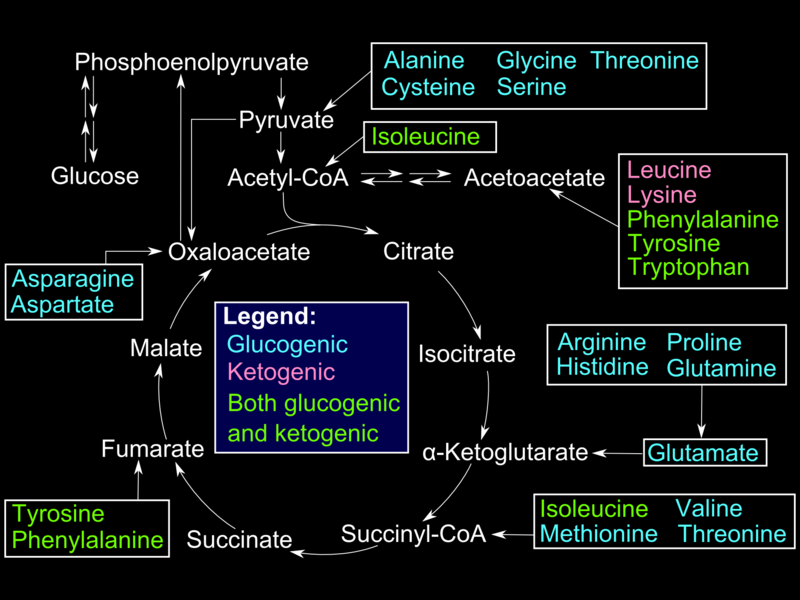

Alanine, produced in skeletal muscles by protein catabolism and subsequent transamination reactions, is shuttled out in blood and taken up by the liver. Inside hepatocytes, alanine undergoes transamination into pyruvate, used for gluconeogenesis. Glucose produced in the liver is shuttled out in circulation and taken up by muscle cells for use in ATP production (Cahill cycle). Other gluconeogenic amino acids (e.g., methionine, histidine, valine) and gluconeogenic and ketogenic (e.g., phenylalanine, isoleucine, threonine, tryptophane) become transaminated into different intermediates of the gluconeogenic pathway.[6]

In red blood cells and other tissues (lens) that lack mitochondria and the exercising muscle tissue that favors anaerobic metabolism, glucose is converted to pyruvate and subsequently to lactate. Lactate is secreted into plasma and picked up by the liver for conversion into glucose (Cori cycle) via a redox reaction catalyzed by lactate dehydrogenase.[7]

Fatty acids are stored as triglycerides and mobilized by the hormone-sensitive lipase (HSL); glycerol from the triglyceride structure is released in blood to be taken up by the liver, phosphorylated by glycerol kinase, and oxidized into dihydroxyacetone phosphate -an intermediate of gluconeogenesis/ glycolysis pathway- by glycerol phosphate dehydrogenase. In contrast to the ketogenic even-chain fatty acids, Odd-chain fatty acids are converted into propionyl CoA during beta-oxidation. After several steps, propionyl CoA is converted into methylmalonyl CoA. Methylmalonyl CoA mutase/B12 catalyzes the conversion of the latter into succinyl-CoA. Succinyl-CoA is an intermediate of the TCA cycle that is eventually converted into oxaloacetic acid and enters the gluconeogenesis pathway. Even-chain fatty acids and purely ketogenic amino acids (leucine, lysine) converted to acetyl-CoA cannot enter gluconeogenesis because the step is catalyzed by pyruvate dehydrogenase (PDH) is irreversible.[8]

In certain conditions, such as ischemic strokes and brain tumor development, astrocytes have increased activity of gluconeogenic enzymes, and they use lactate, alanine, aspartate, and glutamate as substrates.[9]

Regulation of Gluconeogenesis

Multiple factors contribute to the regulation of substrates, enzymes, and reactions involved in gluconeogenesis, including:

- Glucagon regulates gluconeogenesis through[10]

- Changes in allosteric regulators (reduces the levels of fructose-2,6 bisphosphate)

- Covalent modification of enzyme activity (phosphorylation of pyruvate kinase results in its inactivation)

- Induction of enzymes gene expression (glucagon via CRE response elements increases the expression of PEPCK

- Acetyl CoA activates pyruvate carboxylase allosterically[11]

- Substrate availability might increase or decrease the rate of gluconeogenesis

- AMP inhibits fructose-1,6 bisphosphatase allosterically[12]

For gluconeogenesis to occur, the ADP/ATP ratio must be very low since gluconeogenesis is an energy-demanding process requiring high energy molecules to be spent in several steps.[13][14] In between meals, during early fasting, when cells have generated sufficient ATP levels via the TCA cycle, the increased ATP levels inhibit several highly regulated TCA cycle enzymes (citrate synthase, isocitrate dehydrogenase, a-ketoglutarate dehydrogenase). Acetyl-CoA is the indicator of the cells' metabolic activity and functions as a gluconeogenesis regulator at a local level. Acetyl-CoA levels back up and allosterically activate pyruvate carboxylase. This prevents the simultaneous occurrence of gluconeogenesis and the TCA cycle in the cells.[15]

Mechanism

Pyruvate generation from phosphoenolpyruvate is the last irreversible step of glycolysis. Once cells are committed to the gluconeogenesis pathway, sequential reverse reactions convert pyruvate to oxaloacetate and phosphoenolpyruvate (PEP).[16]

- The first step involves pyruvate carboxylase (PC), a ligase that adds a carboxyl group on pyruvate to create oxaloacetate. The enzyme consumes one ATP molecule, uses biotin (vitamin B7) as a cofactor, and uses a CO2 molecule as a carbon source. Biotin is bound to a lysine residue of PC. After ATP hydrolysis, an intermediate molecule PC-biotin-CO2 is formed, which carboxylates pyruvate to produce oxaloacetate. Apart from forming an intermediate for gluconeogenesis, this reaction provides oxaloacetic acid to the TCA cycle (anaplerotic reaction).[11] In muscle cells, PC is used mainly for anaplerosis. The enzyme also requires magnesium. Pyruvate carboxylation happens in mitochondria; then, via malate shuttle, oxaloacetate is being shuttled into the cytosol to be phosphorylated. Malate can cross the inner mitochondrial membrane while oxaloacetic acid cannot. In the cytosol, along with the oxidation of oxaloacetic acid into malate, NAD+ gets reduced into NADH. The produced NADH is used in a subsequent step when 1,3 bisphosphoglycerate converts into glyceraldehyde-3 phosphate.[17]

- The following exergonic reaction catalyzed by PEP carboxykinase (PEPCK), a lyase, uses GTP as a phosphate donor to phosphorylate oxaloacetate and form PEP. Glucocorticoids induce PEPCK gene expression; cortisol, after binding to its steroid receptor intracellularly, moves inside the cell nucleus. Then, the zinc finger domain in cortisol binds to the glucocorticoid response element (GRE) on DNA.[18]

- The rest of the reactions are reversible and common with gluconeogenesis. Enolase, a lyase, cleaves carbon-oxygen bonds and catalyzes the conversion of PEP into 2-phosphoglycerate. Phosphoglycerate mutase, an isomerase, catalyzes the conversion of 2-phosphoglycerate to 3-phosphoglycerate by transferring a phosphate from carbon-2 to carbon-3. Phosphoglycerate kinase using ATP as a phosphate donor and Mg+2 to stabilize with its positive charge, the phosphotransfer reaction converts 3-phosphoglycerate to 1,3- bisphosphoglycerate. Glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase catalyzes the reduction of 1,3-bisphosphoglycerate to glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate. NADH is oxidized as it donates its electrons for the reaction. As described earlier, glycerol phosphate from triglyceride catabolism is converted eventually into DHAP. Triosephosphate isomerase converts DHAP into glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate. Aldolase A converts glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate into fructose-1,6 bisphosphate.[19]

- The following irreversible step involves the conversion of fructose 1,6 bisphosphate into fructose-6 phosphate. This step is important as it is the rate-limiting step of gluconeogenesis. Fructose-1,6 bisphosphatase catalyzes the dephosphorylation of fructose-1,6 bisphosphate, requiring bivalent metal cations (Mg+2, Mn+2); this is a highly regulated step by global and local stimuli. Locally, increased ATP levels and increased citrate levels (the first intermediate of the TCA cycle) activate fructose-1,6 bisphosphatase. However, increased AMP and increased fructose-2,6 bisphosphate (F2,6BP) inactivate this enzyme. Glucagon binds to its receptor, a GPCR, and activates adenylate cyclase. The subsequent increase in cyclic AMP (cAMP) levels leads to the activation of protein kinase A (PKA). PKA phosphorylates fructose 2,6 bisphosphatase (F2,6BPase) and phosphofructokinase-2 (PFK-2). Phosphorylated PFK-2 is inactive, while F2,6BPase is active and catalyzes the dephosphorylation of fructose 2,6 bisphosphate. Dephosphorylated F-2,6BP is inactive; hence, it does not negatively affect F1,6BPase.[20][21]

- The last irreversible reaction involves glucose-6 phosphatase catalyzing the hydrolysis of glucose-6 phosphate into glucose. This enzyme is expressed primarily in the liver, kidneys, and intestinal epithelium, and the reaction happens in the endoplasmic reticulum of the cells. Muscle cells do not express glucose-6 phosphatase as they produce glucose to maintain their energy needs.[22]

Clinical Significance

Glycogen Storage Disease Type 1 - Von Gierke Disease

Glycogen storage disease type 1 is a group of inherited complex metabolic disorders which share poor fasting tolerance.[23] In Von Gierke disease, liver cells lack glucose-6 phosphatase, the enzyme required to release glucose from liver cells. This disease affects both glycogenolysis and gluconeogenesis since the missing enzyme is common in both pathways resulting in the accumulation of glucose-6 phosphate in liver cells. Symptoms include:

- Hepatomegaly and kidney enlargement due to glycogen accumulation

- Severe fasting hypoglycemia since liver cells cannot release glucose in blood postprandially

- Lactic acidosis since accumulated glucose-6 phosphate blocks gluconeogenesis and consequently lactate uptake

- Hypertriglyceridemia, since increased levels of glucose-6 phosphate favor glycolysis and acetyl-CoA production, leading to increased malonyl-CoA synthesis and subsequent inhibition of carnitine acyltransferase 1 (the rate-limiting mitochondrial enzyme of fatty acid beta-oxidation)[24]

Hyperuricemia results from increased uric acid production and decreased uric acid excretion (uric acid competes with lactate for excretion via the same organic acid transporter in proximal renal tubules).[25][24] Other symptoms include protruding abdomen (hepatomegaly), truncal obesity and short height,[26] muscle wasting, and a rounded doll’s face.[25]

Pyruvate Carboxylase Deficiency

Pyruvate carboxylase deficiency is due to the lack of pyruvate carboxylase or altered enzyme activity. It causes lactic acidosis, hyperammonemia, and hypoglycemia. Hyperammonemia is due to pyruvate not being converted into oxaloacetic acid. Oxaloacetic acid gets transaminated into aspartate; reducing aspartate levels results in the reduced introduction of ammonia into the urea cycle.[27]