Introduction

Eyelashes develop from ectoderm between weeks 22 and 26 of gestation. Although the length varies from person to person, they do not grow beyond a certain length and then fall off by themselves. They generally do not need trimming unless there is excessive growth (trichomegaly). If a person pulls a lash out, it takes about 8 weeks to grow back. Eyelash hair is not affected by puberty. Eyelash follicles are 2.4-mm deep in the upper lid and 1.4 mm in the lower lid. There are more active lash follicles in the upper lid compared to the lower lid (41% vs. 15%).[1] The function of eyelashes is to protect the eyes from particulate matter. They are also highly innervated, making them sensitive (have been compared to cat's whiskers) to touch and again help protect the eyes. The human lower eyelid has 75 to 80 lashes in three to four rows, whereas the upper eyelid has 90 to 160 lashes scattered on five to six rows. Each lash has a hair shaft that extends outside the skin, a root that is under the skin, and a bulb that is the enlarged terminal portion. The inferior portion of the bulb is in direct contact with the dermal papilla, which brings key mesenchymal-epithelial interactions in follicle cycling.

Unlike the scalp, which has the epidermis, dermis, and hypodermis, eyelid skin is thinner with only the epidermis and dermis. Lash follicles also do not have arrector pili muscles which straighten the hair in response to cold or intense emotions.

Definition of Conditions

Cilia incarnata is the misdirection of eyelashes whereby they grow under the skin through to the surface or posteriorly to the conjunctival surface instead of emerging normally from the eyelid margin.

Two types are recognized:

- Cilium incarnatum internum

- Cilium incarnatum externum

Etymology: Latin Derivatives

Cilium is a neuter noun whose plural is cilia or cilii).

Incarnata is the neuter plural of incarnatus, which is the perfect passive participle of incarno, which means "to make or become flesh."

Incarnatum is the first supine of incarno.

Internum is the adjective neuter form meaning "internal" or "inward."

Externum is the adjective neuter form meaning "external" or "outward."

The word incarno, from which incarnata and incarnatum are derived imply inflamed, or red and fleshy, as in the Crimson Clover named Trifolium incarnatum because of its deep crimson color. In the conditions under discussion, there is no inflammation or redness of the eyelid in either of the conditions, and cilium incarnatum internum only causes irritation of the cornea and sometimes a conjunctival inflammation, but no fleshy or inflamed appearance.

With that in mind, a more accurate description of these two conditions, derived from the Latin, would be as follows:

Cilium crescere internum: literally meaning lash growing inward

Cilium crescere externum: literally meaning lash growing outward.

History and Physical

Cilium Incarnatum Internum

Most patients with cilium incarnatum internum will present with a history of a foreign body sensation. The onset is usually sudden and often only a few days old. Some patients will observe that the eye is more uncomfortable in a particular gaze, depending upon the site of the lash protruding through the tarsal conjunctiva. Examination of the eye may reveal punctate keratopathy with conjunctival inflammation, which may be mistaken for episcleritis, and the patient may have photophobia because of the keratitis. Unless the physician examines the eyelid margin and the everted eyelid margin carefully with the biomicroscope, these lashes may be missed. Sometimes, just a dark spot showing the tip of the lash protruding through the tarsal conjunctiva may be visible.

Any patient presenting with either keratitis, unilateral conjunctivitis, conjunctival injection, photophobia, or episcleritis should be examined on the slit lamp to exclude trichiasis, foreign bodies, and cilium incarnatum internum.

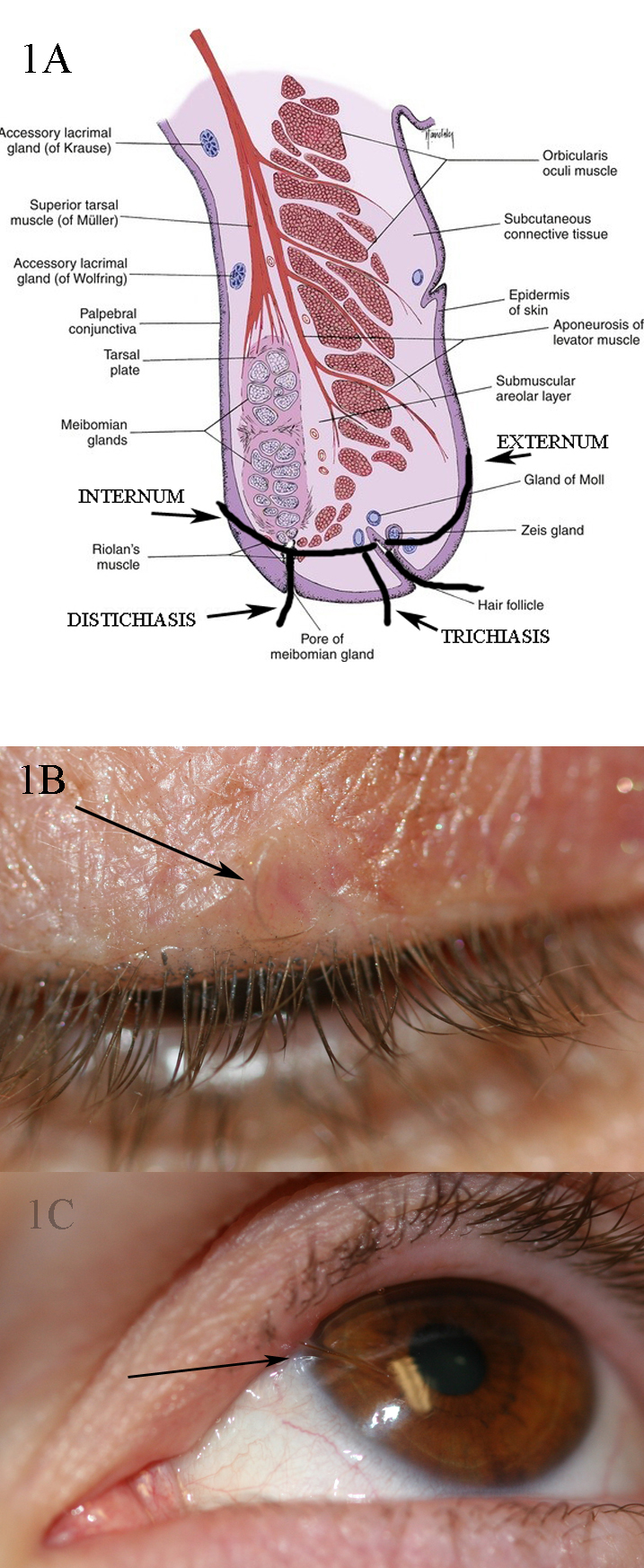

Cilium Incarnatum Externum

These are usually asymptomatic, although some patients may present with a complaint of a bump, indicating the elevation around the buried eyelash. Sometimes, a patient may complain of a sharp discomfort on rubbing his eyelid, especially if the tip of the hair comes through the skin, which is usually not the case. There is usually no evidence of inflammation, ulceration, or bleeding. The lash can usually be identified coursing under the eyelid skin (see photograph).

Differential Diagnosis

Specific conditions that should be considered when encountering cilia incarnata.

Several conditions present with eyelashes growing abnormally, from abnormal locations, in abnormal directions, or with different characteristics. Discussion of these various conditions will allow the reader to understand the differential diagnosis when examining such patients.

Trichiasis

Definition

Trichiasis is normal lashes growing inward. In other words, the problem is with lash growth direction and not with the lash follicle position. There are often more lashes in the presence of surrounding inflammation, such as in the presence of trachoma. It is an acquired condition, where eyelashes that grow normally are turned inward and are usually associated with some pathological in-turned condition of the lid. These patients will also present with a foreign body sensation and have corneal irritation.

Causes

Most trichiatic lashes affect the lower eyelid centrally except in trachoma or chemical burns, where both eyelids may be affected. Most patients will have bilateral trichiasis. The cause of trichiasis is usually scarring of the lid margin secondary to inflammation. Trichiasis can cause infections and scarring of the cornea with eventual corneal opacification. Trachoma is the result of Chlamydia trachomatis infection and a common cause of trichiasis in sub-Saharan Africa. Other causes of trichiasis include blepharitis, meibomian gland dysfunction, vernal keratoconjunctivitis, chemical or thermal burns, Herpes zoster, actinic elastosis, atopic diseases, eczema, and leprosy. Ocular cicatricial pemphigoid disease, Stevens-Johnson syndrome, trauma, and surgery can cause trichiasis. Basal cell carcinoma or any other eyelid malignancy can cause trichiasis as well as loss of lashes. Sometimes one will see trichiasis at a site of a prior chalazion which may or may not has been surgically drained. The collapsed meibomian gland can cause a local change in the architecture with lashes turning in. Slit-lamp examination is vital when evaluating trichiasis. It is important to look for fornix shortening with symblepharon formation as this will indicate a cicatrizing process. Trichiasis is differentiated from involutional entropion, where the eyelid margin turns in and causes normal lashes to rub against the cornea. This is often termed secondary trichiasis or pseudo-trichiasis.

Treatment

Simple epilation and use of a bandage contact lens will give immediate relief. Surgical treatment should be deferred until any active inflammation is controlled. Techniques used to treat these trichiatic lashes include the use of the radiofrequency needle to the depth of the root of the lashes (2.4-mm deep in the upper lid and 1.4 mm in the lower lid), cryotherapy, and monopolar electrolysis (which is used less frequently now because of associated collateral injury to tissues).

Distichiasis

Definition

There is a separate set of eyelashes behind the normal row of lashes. These lashes are often softer and finer and without pigmentation. There may be a fully formed additional row of lashes, or there may be a sporadic series of lashes.

Causes

Congenital distichiasis can be autosomal dominant: the second row of lashes grows out of the meibomian glands. Instead of differentiating into meibomian glands, pilosebaceous units differentiate into hair follicles. The meibomian glands (modified sebaceous glands) are very rudimentary, and sometimes only acini are present. In the autosomal lymphedema-distichiasis syndrome, patients will have distichiasis, limb lymphedema, cleft palate, extradural cysts, cardiac deformities, and photophobia. Distichiasis may also be seen in mandibulofacial dystonia. Setleis syndrome has focal facial dermal dysplasia with upper eyelid lashes present in multiple rows, or eyelashes may be completely absent. Secondary causes of distichiasis are similar to those seen in trichiasis, namely, blepharitis, caustic injuries, meibomian gland dysfunction, meibomianitis, ocular cicatricial pemphigoid, and Stevens-Johnson syndrome.

Treatment

Treatment includes epilation with forceps, epilation with electrolysis, cryoprobe, electrocautery, radiofrequency, trephination, or folliculectomy. In some patients, the lids have to be split surgically to treat the second row of lashes individually. Some patients may need the application of a mucous membrane graft, especially if there is mucocutaneous keratinization.

Tristichia and Tetrastichiasis

This is a very rare occurrence of three or four rows of lashes, respectively.

Eyelash in Meibomian Gland or Punctum (Termed "pseudocilium" as it is not a true lash with a true root and the term allows us a defined diagnosis with one word)

Definition

A loose lash will be seen coming out of an isolated meibomian gland or the punctum.

Causes

A loose lash is thought to find its way into the opening of a meibomian gland or into the punctum. Cases have been described with the root on the outside and also with the root on the inside of the meibomian gland. It is felt that this is a simple case of a lost lash finding its way into a meibomian gland or the punctum with no other underlying disease. The lash tends to sit in the gland or the punctum very loosely with no surrounding attachments (unlike in distichiasis and other conditions causing metaplastic changes in the meibomian glands). Also, it is generally a solitary lash that will be found.

Treatment

Simple removal of the lash from the meibomian gland or the punctum is curative.

Hypertrichosis

Definition

Hypertrichosis is an increase in hair beyond the normal variation for a patient's age, sex, or ethnicity. Eyelash hypertrichosis is known as trichomegaly.

Causes

Congenital hypertrichosis lanuginosa and congenital generalized hypertrichosis cause generalized hypertrichosis that involves the periocular region and most of the body. Numerous other conditions and syndromes are associated with hypertrichosis (or trichomegaly), including neurofibroma, Cornelia de Lange syndrome, Goldstein Hutt syndrome, phenylketonuria,tType I oculocutaneous albinism, tyrosinemia, among others.

Acquired trichomegaly is seen secondary to irritation or inflammation. It may be caused by endocrine and metabolic diseases as well as a paraneoplastic process; therefore, a thorough investigation for malignancy is needed. Trichomegaly is also seen in anorexia nervosa, dermatomyositis, hypothyroidism, malnutrition, pregnancy, pretibial myxedema, porphyria, systemic lupus erythematosus, vernal keratoconjunctivitis, and uveitis. HIV/AIDS may cause trichomegaly as well as madarosis. Many drugs have been associated with trichomegaly, causing thickening and even curling. The most common of them being prostaglandin analogs used to treat glaucoma (e.g., latanoprost, bimatoprost), epithelial growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitors (e.g., erlotinib), zidovudine, cyclosporine, topiramate, tacrolimus, and interferon-alpha.

Treatment

Treatment, when needed, is similar to the treatments outlined under trichiasis if there is associated trichiasis or the increased hair causes irritation of the eye.

Eyelash Ptosis

Definition

Downward sloping or bending of upper eyelid lashes and follicles.

Causes

The most typical causes are the use of prostaglandin analog drops for glaucoma, which causes trichomegaly and secondary mechanical lash ptosis, and the floppy eyelid syndrome, which causes eyelash ptosis and loss of eyelash parallelism. Patients with floppy eyelid syndrome are easily diagnosed as they will give a history of weight loss and gain, the eyelids are floppy and evert easily, and there is a papillary conjunctival inflammation with discharge. These patients will be obese and frequently have obstructive sleep apnea. Patients present with discharge, irritation, redness, and corneal ulcer formation. Other causes of eyelash ptosis include congenital ptosis, acquired ptosis, dermatochalasis with anterior lamellar slide, and congenital lamellar acanthosis. Upper eyelid margin entropion may appear as apparent eyelash ptosis. This is often seen in patients with facial nerve palsy.

Normal eyelash position and direction are dictated by the orbicularis oculi muscle, the associated Riolan muscle, the tarsal plate, and eyelid elastin. Injury or deformity of these structures results in lash ptosis. Abnormal elastin in floppy eyelid syndrome is thought to contribute to lash ptosis. Eyelash ptosis of the lower lids (upward slanting lashes) is seen in the condition of congenital epiblepharon and patients with thyroid orbitopathy, although this is more of a mechanical malposition caused by surrounding structures (the orbicularis in epiblepharon and proptosis and periorbital edema in thyroid orbitopathy).

Treatment

Treatment depends upon the cause. We tell all patients with floppy eyelid syndrome that a permanent cure is defined and long-term weight loss. Indeed, we have seen impressive improvement without any surgical treatment when a patient successfully loses and maintains the decreased weight. Conservative treatments like ointment use and wearing of a shield give little relief. Surgical resection of redundant rubbery upper and lower eyelids in a full-thickness manner is reserved for recalcitrant cases, with the proviso that this does not cure the condition and merely helps to create a firmer eyelid to protect the cornea. Cessation of prostaglandin analogs causes a reversal of the lash changes within a few months in patients with glaucoma drop-induced lash ptosis.

Cilium Inversum (meaning "upside down lash")[3][4][5]

Definition

The finding is exactly that seen in cilium incarnatum internum, in that a lash will grow inwards. Historically, this term cilium inversum was used when the condition was congenital. However, it has also been used interchangeably with findings which are exactly those seen in cilium incarnatum internum in adults: Tibbles (in 1923 in the BMJ) first reported of its occurrence in a woman of 21 years, who after having the trouble of irritation for three weeks presented two such in-growing eyelashes. One was at the posterior border of the lid margin, and the other one appearing in the subtarsal sulcus. Duke-Elder (1952) mentions Schrieber (1924) as the next one to report it. No mention of such cases is found in the literature after that. Authors of this article propose that this term is dropped as it simplifies matters to call the condition "congenital cilium incarnatum internum."

Treatment

Simple epilation cures the condition.

Ectopic or Accessory Cilia[6]

Definition

Lashes that are found outside their normal area that is the eyelid margin. Weigmann first described ectopic cilia in 1936.

Causes

Lashes may grow through the eyelid with the root of the lashes in the tarsal plate but not at the lid margin. This is seen congenitally but can also occur secondary to trauma, in which case accessory cilia have been found in eyelids as well as intraocularly. There has been a report of positive family history in one case report of ectopic cilia growing through the upper part of the eyelid.[6] Ectopic or accessory cilia are caused by an abnormal location of the lash follicles, unlike cilia incarnata. With accessory cilia, histology will reveal the presence of apocrine sweat glands attached to the follicle, which is necessary to diagnose the hairs as eyelashes.

Treatment

Treatment depends upon the location, the number of lashes, and the effects. Essentially surgical, laser, or cryotherapy treatments are used to remove the abnormal lashes permanently.

Buried Lash with Granuloma

Definition

A loose lash may bury itself through the conjunctiva and cause local inflammation. This may be seen on the tarsal conjunctiva or, more infrequently, in the forniceal conjunctiva.

Causes

Granuloma is caused in reaction to a lash that acts as a foreign body.

Treatment

Although simple removal of the lash may be curative, there have been instances where the root needs to be more aggressively removed to cure the condition.

Vellus Hair Cyst Eyelid/Orbit[7]

Definition

Cysts lined by squamous epithelium filled with vellus hairs and keratin. There have been rare instances of these reported in the eyelid and one recent report of such a lesion in the orbit.

Causes

Granuloma is caused in reaction to a lash that acts as a foreign body.

Treatment

Complete removal of the cystic lesion is needed via an orbitotomy if necessary.