Continuing Education Activity

Pseudoaneurysms are false aneurysms occurring at the site of arterial injury from trauma or infection. Unlike true aneurysms in which the blood vessel wall balloons, a pseudoaneurysm does not involve the vascular wall. Instead, blood leaks from the injury site and is contained by a wall developed with the products of the clotting cascade. The most commonly encountered pseudoaneurysms include cardiac, femoral, visceral, and aortic pseudoaneurysms. These pseudoaneurysms are separate disease entities that occur in many situations and require specific workup and treatment. Prompt recognition and treatment are required. The characteristics of the false aneurysm (eg, size, location, and complicated type) guide the treatment of choice, especially for femoral pseudoaneurysms.

This activity for healthcare professionals aims to enhance learners' competence in selecting the appropriate diagnostic tests and management for pseudoaneurysms and fostering effective interprofessional teamwork to improve outcomes.

Objectives:

Identify the risk factors for developing pseudoaneurysms, specifically femoral, visceral, and aortic pseudoaneurysms.

Determine the evaluation strategy for each type of pseudoaneurysm.

Implement the recommended management for each type of pseudoaneurysm.

Implement interprofessional team strategies for improving care coordination and communication and improve outcomes with regard to pseudoaneurysms.

Introduction

An arterial pseudoaneurysm, otherwise known as a false aneurysm, is an uncommon but well-known condition that can occur at any arterial site after an arterial puncture, which results in a locally contained turbulent blood flow forming a hematoma with a neck that typically does not close spontaneously beyond a specific size.[1] Pseudoaneurysms may also result following arterial injury due to trauma or infection. Unlike true aneurysms in which the blood vessel wall balloons, a pseudoaneurysm does not involve the vascular wall. Instead, blood leaks from the injury site and is contained by a wall developed with the products of the clotting cascade. Eventually, a wall forms from fibrin and platelet crosslinks that are ultimately weaker than those of a true aneurysm. The most commonly encountered pseudoaneurysms include cardiac, femoral, visceral, and aortic pseudoaneurysms. These pseudoaneurysms are separate disease entities that occur in many situations and require specific workup and treatment.

The most common clinical presentation of a pseudoaneurysm is a femoral pseudoaneurysm that develops following arterial access placement for endovascular procedures. Prompt recognition and treatment are required. Typically, most superficial pseudoaneurysms present as a painful, pulsatile mass with symptoms developing within 24 hours of arterial injury or insulting procedure. The recommended imaging studies for diagnosing a pseudoaneurysm depend on the location; however, angiography and duplex ultrasonography are most commonly utilized to evaluate the size, anatomy, and origin. The characteristics of the false aneurysm (eg, size, location, and complicated type) guide the treatment of choice, especially for femoral pseudoaneurysms.

Etiology

Depending on the type of pseudoaneurysm, the etiology is either iatrogenic or noniatrogenic.

Femoral pseudoaneurysm: Iatrogenic etiologies are the most common cause of a femoral pseudoaneurysm, including arterial access for endovascular procedures, with an incidence of less than 1% and anastomotic failure. The less common noniatrogenic causes include trauma, infection, and pancreatitis with pseudocyst/pancreatic fistula.[2]

Aortic pseudoaneurysm: This type of pseudoaneurysm often results from blunt or penetrating trauma, infection, atherosclerotic penetrating/degenerative lesions, and anastomotic sites following vascular bypass or repair.

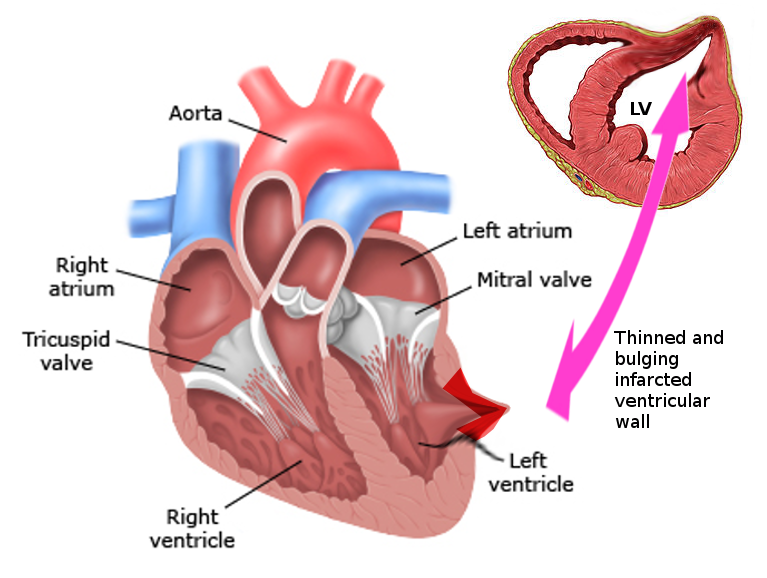

Cardiac pseudoaneurysm: These pseudoaneurysms can occur following an acute myocardial infarction, postoperative following mitral valve surgery or congenital heart surgery, endocarditis, and trauma.[3] (see Image. Left Ventricular Pseudoaneurysm)

Visceral artery pseudoaneurysm: Pseudoaneurysms of this type can occur following noniatrogenic (eg, pancreatitis with pseudocyst formation) and iatrogenic causes (eg, following catheter-based interventions).

Iatrogenic Pseudoaneurysm Risk Factors

Risk factors for pseudoaneurysms that are iatrogenically caused include:

- Hypertension

- Female sex

- Anticoagulant use

- Placement of access to the left femoral artery

- Puncture of calcified blood vessels

- Larger sheath size, greater than 6 French

- Obesity

- Lack of ultrasound utilization during an access procedure

- Multiple puncture attempts [4][5]

Epidemiology

The incidence of pseudoaneurysms varies based on the location, including cardiac, femoral, visceral, or aortic.

Aortic pseudoaneurysm: These can result from trauma, penetrating aortic lesions, or even secondary to infected aortic valves.[6][7] Of those with aortic injuries secondary to blunt trauma, an estimated 85% die before reaching medical care. Approximately 90% of blunt thoracic aortic injuries occur just distal to the aortic isthmus and are a result of deceleration injury from tethering to the ligamentum arteriosum.[8] Aortic pseudoaneurysm is considered a grade III aortic injury, now most commonly treated with thoracic endovascular aortic repair (TEVAR) rather than open surgery.[9] Rarely, the cause of thoracic aortic pseudoaneurysms is advanced tuberculosis.[10] Of the iatrogenic causes, pseudoaneurysm formation can occur following aortobifemoral bypass, with an incidence of 3.8%.[11]

Cardiac pseudoaneurysm: This type of pseudoaneurysm most commonly develops following an acute myocardial infarction. One study out of the Mayo Clinic found that 55% of cardiac pseudoaneurysms developed following a myocardial infarction, with the inferior wall being twice as affected as the anterior wall, unlike true left ventricular aneurysms.[12] The other common causes include postoperative following mitral valve surgery or congenital heart surgery, the etiology of 33% of cases, as well as endocarditis, trauma, and idiopathic.[3] There are also cases of coronary artery pseudoaneurysms developing following a heart transplant.[13]

Femoral pseudoaneurysm: These pseudoaneurysms typically result from access following catheter-based interventions for cardiac and noncardiac procedures and carry an incidence of 0.6% to 4.8% in some studies, but more recently are reported to occur in less than 1% of all procedures.[14] [15] With the increasing use of ultrasound for access, some society guidelines quote that the acceptable rate of pseudoaneurysm after percutaneous access should be less than 0.2%.[16]

Visceral artery pseudoaneurysms: These can be seen in association with those suffering from chronic pancreatitis.[17] Splenic artery pseudoaneurysms are the most common pseudoaneurysm formation but are least likely to rupture. There are also reports of uterine artery aneurysms following the placement of a cervical cerclage.[18]

Pathophysiology

The pathophysiology of pseudoaneurysms depends on their site and location.

Aortic Pseudoaneurysms

Aortic pseudoaneurysms due to blunt trauma are theorized to be caused in large part by deceleration forces between the relatively free aortic arch against the relatively fixed descending aorta, especially at the point where the ligamentum arteriosum anchors the aorta to the pulmonary artery. This fact, in combination with the pinching effect between the sternum and the spine and the water hammer effect caused by squeeze forces, can cause partial to total rupture of the thoracic aorta.[8]

Femoral Pseudoaneurysms

Femoral pseudoaneurysms after percutaneous access can occur due to any of the following:

- Failures of closure devices

- Double wall entry of the anterior and posterior artery with continued bleeding from the posterior puncture site

- Laceration of the branches of the common femoral artery, including the deep femoral, superficial femoral, or other arteries (eg, external iliac, inferior epigastric)

- Inadequate pressure or length of time holding pressure postprocedure

- Inadvertent access or dilation of the artery during venous procedures [19]

Femoral graft anastomosis can also break down over time due to suture failure or, more commonly, infection of the graft material.

Cardiac Pseudoaneurysms

Cardiac pseudoaneurysms do not contain endocardium or myocardium, unlike true aneurysms, and are contained by pericardium or developing scar tissue.

Visceral Pseudoaneurysms

Visceral pseudoaneurysms are known to be very rare and are usually related to occurring iatrogenically from injury during surgery or endovascular procedures or following an episode of pancreatitis. When pseudoaneurysms occur following pancreatitis, they typically present as a splenic artery pseudoaneurysm. This is thought to occur secondary to the digestive action of pancreatic enzymes on the artery.[20] Unlike true aneurysms, visceral pseudoaneurysms appear in myriad locations. One study found the distribution of visceral artery pseudoaneurysms to be the celiac axis and its branches in 39% of cases, hepatic arteries in 39%, splenic arteries in 18%, and superior mesenteric artery in 4% of cases.[21]

History and Physical

The history and exam findings depend on the location and type of pseudoaneurysm present.

Femoral Pseudoaneurysm

Typically, most superficial femoral pseudoaneurysms present as a painful, pulsatile mass with symptoms developing within 24 hours of arterial injury or insulting procedure. The mass will frequently exhibit a bruit on auscultation. Commonly, ultrasound findings on duplex imaging demonstrate a classic to-and-fro or bidirectional swirling flow quality described as a classic yin-yang sign. Enlarging pseudoaneurysms may exhibit pressure on the skin with resultant rubor, pain, and, ultimately, skin ischemia, necrosis, and hemorrhage. The physical exam findings of a pulsatile mass in the groin carry a 92% sensitivity and 93% specificity in diagnosing a femoral pseudoaneurysm.[22] If a patient with a femoral pseudoaneurysm displays any of the following findings, emergent surgical assessment is recommended:

- Expanding hematoma

- An attributable motor or sensory neurologic deficit

- An attributable pulse deficit

- Hemodynamic instability

- Ischemic and extensive skin and subcutaneous damage

- Surrounding or adjacent infection (eg, abscess, purulent drainage, cellulitis, fever, leukocytosis) [23]

Aortic and femoral pseudoaneurysms are rarely spontaneous, so a history of a recent interventional procedure can be helpful. Also, the presence of intravenous drug use can suggest the presence of a mycotic pseudoaneurysm.[24] This history is essential as repair of these can be challenging, given the lack of usable veins for conduit in drug abusers as well as grossly infected fields.

Cardiac Pseudoaneurysm

Cardiac pseudoaneurysms most commonly present with chest pain and shortness of breath, with some reporting no symptoms (12%-48%) and around 3% presenting with cardiac arrest.[3] On physical exam, systolic ejection murmurs resembling mitral regurgitation type murmurs are heard in almost two-thirds of patients, along with various ECG abnormalities like ST-elevations, and many will have masses seen on chest x-rays (>50%).

Visceral Artery Pseudoaneurysm

Approximately 91% of visceral artery pseudoaneurysms do not present with symptoms until that of rupture. This presentation was historically termed abdominal apoplexy.[25]

Evaluation

The recommended imaging evaluation for a patient with a known or suspected pseudoaneurysm depends on the location. Duplex ultrasonography for superficial femoral pseudoaneurysms remains the gold standard for diagnosis, as it can also evaluate the size, anatomy, and origin of pseudoaneurysms. Studies show that duplex ultrasound imaging has a sensitivity of 100%. If needed, a computer tomography angiogram (CTA) can help define the relation to surrounding structures and help characterize the pseudoaneurysm, which can help guide treatment. However, computer tomography (CT) imaging is not required to diagnose or evaluate a femoral artery pseudoaneurysm.

However, CTA or conventional arteriography is utilized to diagnose aortic pseudoaneurysms. Aortic pseudoaneurysms may have a history of previous open repair of dissection or aneurysm, blunt or penetrating trauma, infection, or genetic disorders which cause a predisposition to aneurysmal degeneration of the aorta (eg, Marfan syndrome or Ehlers-Danlos syndrome).

Angiography is most commonly used to diagnose most other types of pseudoaneurysms. For diagnosing cardiac and visceral pseudoaneurysms, angiography is the gold standard with a sensitivity of more than 85%.[12] Although a transthoracic echocardiogram can detect cardiac aneurysms, it has been shown to give a definitive diagnosis in only around 25% of cases.[26] However, transesophageal echocardiography has a much better sensitivity at approximately 75% than angiography. On echo, the pseudoaneurysms will have a narrow neck that is usually less than 40 percent of the maximal aneurysm diameter. In contrast, a true aneurysm will have a wide neck as its apex. Other techniques include cardiac computerized tomography and magnetic resonance imaging. These modalities can also characterize an aneurysm as true or false.[27] Visceral pseudoaneurysms can present with signs of bleeding and abdominal pain, and if suspected, a CT angiography or conventional angiography can help diagnose and characterize these pseudoaneurysms as well.

Treatment / Management

The characteristics of the false aneurysm (eg, size, location, and complicated type) guide the treatment of choice.

Aortic Pseudoaneurysm

Aortic pseudoaneurysms are now preferably treated with thoracic endovascular aortic repair (TEVAR) or endovascular aneurysm repair (EVAR).[28] Even in mycotic pseudoaneurysm and tuberculous pseudoaneurysm of the aorta, prosthetic stent grafts can be lifesaving and avoid the need for a large open operation in already debilitated patients.[10]

Femoral Artery Pseudoaneurysm

The treatment approach for femoral artery pseudoaneurysms is based on various factors, including size, location, and whether the pseudoaneurysm is classified as complicated or uncomplicated. The following management options below discuss the different recommendations.

Visceral Artery Pseudoaneurysm

Visceral artery pseudoaneurysms are typically treated by endovascular means first, with surgery reserved for failure; this is highly effective, with one study reporting a 98% success rate in control of pseudoaneurysms and ruptured true aneurysms.[25] Techniques include coiling, injections of procoagulant materials, and covered stent deployment to seal the origin of the pseudoaneurysm.

Differential Diagnosis

Differential diagnosis of a femoral pseudoaneurysm includes:

- Hematoma

- Seroma

- Infection or abscess

- True aneurysm

Prognosis

The overall prognosis for most pseudoaneurysms is good but depends on the location. For femoral aneurysms less than 3 cm, conservative management with observation has resolution rates ranging from 50% to 100%.[4][29]. The high success rates are not seen as often in those on dual antiplatelet therapy, as the failure rates seen have been upwards of 44%.[14] Ultrasound-guided thrombin injection for femoral pseudoaneurysms caused by vascular access has a high success rate of up to 97% to 100%, even in those taking anticoagulants or antiplatelet agents. Those that fail can undergo a second attempt, and very few should require surgical correction.[16]

Though not studied well, endovascular repair of visceral pseudoaneurysm carries a high technical success rate in small series. However, open repair and ligation are considered more durable and may be a better option for younger patients.[17] Cardiac pseudoaneurysms are highly fatal if left untreated and carry almost a 45% risk of rupture, with a mortality rate of 50% in those only getting medical therapy.[31][12] Traumatic aortic pseudoaneurysms treated with TEVAR have an excellent technical success rate of 100%, a low rate of device-related complications of 2.4%, and a conversion rate to open procedure of 2.4%. Coverage of the left subclavian artery resulted in a 6% rate of delayed revascularization.[32]

Complications

Complications of all types of pseudoaneurysms include distal embolization, rupture, bleeding, and death. Femoral pseudoaneurysms can rupture into the retroperitoneal space, causing significant bleeding that may not be immediately obvious, which can lead to death.

Complications of ultrasound-guided thrombin injection include distal embolization in up to 2% of patients, though few require any intervention.[33]

Complications of endovascular repair of visceral and aortic pseudoaneurysms are primarily those related to endovascular devices and will not be discussed in depth here.

Postoperative and Rehabilitation Care

Open repair of femoral pseudoaneurysms requires no special postoperative care above the standard care of vascular patients, and the need for rehabilitation is primarily predicated on the patient’s overall condition before intervention. Endovascular repair of pseudoaneurysms is generally well-tolerated, and the patient should remain flat for 2 to 4 hours postprocedure with monitoring for the development of subsequent access site pseudoaneurysm. Repairs involving stent or graft device deployment will require long-term follow-up with a vascular surgeon for surveillance imaging.

Consultations

A cardiac or vascular surgeon consultation is necessary for all pseudoaneurysms. A vascular surgeon or interventional radiologist can perform ultrasound-guided compression and thrombin injection, but only a vascular surgeon can treat femoral artery pseudoaneurysms that require surgery.

Deterrence and Patient Education

There are no specific recommendations for the deterrence of pseudoaneurysms. However, patients with a history of pseudoaneurysm should be made aware of the signs and symptoms of pseudoaneurysms in case of recurrence. Additionally, patients should be counseled on the signs and symptoms of pseudoaneurysm before vascular procedures due to the risk of occurrence.

Pearls and Other Issues

Femoral pseudoaneurysms following vascular access are the most common cause of pseudoaneurysms, and treatment by a less invasive means is preferred rather than open surgery. Pseudoaneurysms that occur during vascular anastomosis mandate open repair and revision. Visceral pseudoaneurysms are uncommon and are often diagnosed during an investigation for vague symptoms of abdominal pain or with CTA imaging for signs of bleeding. Aortic pseudoaneurysms are rarely spontaneous and result either from infection or trauma. Cardiac pseudoaneurysms are highly fatal if left untreated and carry almost a 45% risk of rupture, with a mortality rate of 50% in those only getting medical therapy.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

The management of pseudoaneurysms requires an interprofessional team approach, including physicians, specialists, and specialty-trained nurses collaborating across disciplines to achieve optimal patient results. The management of pseudoaneurysms relies heavily on their location and size. Nurses and physicians should routinely palpate the groin area after patients undergo cardiac catheterization, as pseudoaneurysms are not uncommon. Depending on local practice patterns, a femoral pseudoaneurysm can be treated by the vascular surgeon or by interventional radiology with thrombin injection. A vascular surgeon or interventional radiologist may also perform endovascular repair of visceral artery pseudoaneurysms. Aortic pseudoaneurysms are typically the domain of the vascular surgeon, as there is a possible need for open repair and subsequent follow-up. Only the vascular surgeon can perform open repairs of all types of pseudoaneurysms.