Introduction

The salivary glands are exocrine glands that make, modify and secrete saliva into the oral cavity. They are divided into two main types: the major salivary glands, which include the parotid, submandibular and sublingual glands, and the minor salivary glands, which line the mucosa of the upper aerodigestive tract and the overwhelming entirety of the mouth [1].

Human salivary glands produce between 0.5 to 1.5 L of saliva daily, facilitating mastication, swallowing, and speech, lubricating the oral mucosa, and providing an aqueous medium for taste perception. They also participate in the digestion of triglycerides and starches by secreting lipases and amylases. In addition, saliva plays a protective role against infections via its many organic constituents. These include the secretory piece, a glycoprotein that forms a complex with immunoglobulin A (IgA) to defend against viruses and bacteria, lysozymes that cause bacterial agglutination, autolysin to degrade bacterial cell walls, and lactoferrin to sequester iron (an element vital to bacterial growth) [2]. Additionally, saliva contains ionic compounds, such as bicarbonates, that buffer acids produced by bacteria and protect the oral cavity and esophagus from gastric juice. As a result, saliva plays a vital role in protecting the mouth from chronic buccal mucosal infections and dental caries [3].

Structure and Function

Anatomical Location

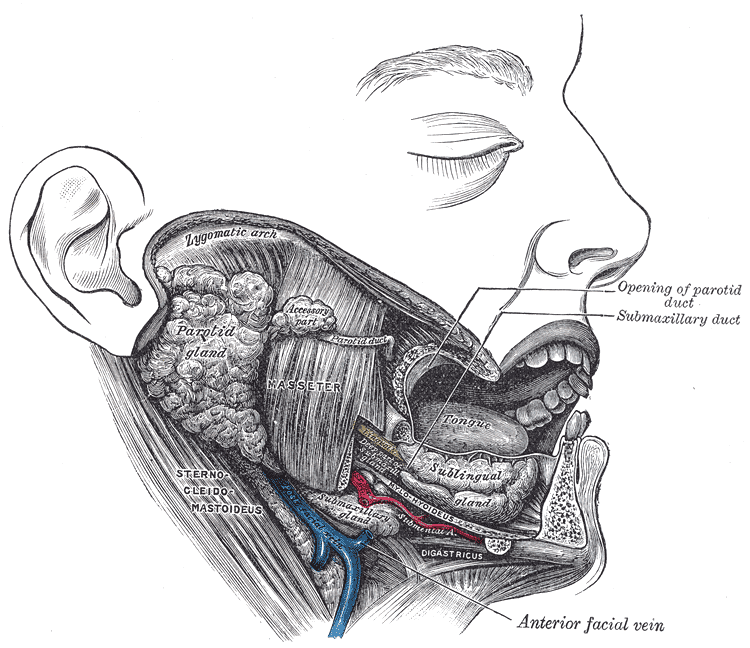

The parotid gland (PG) is the largest of the three major salivary glands. It is located between the sternocleidomastoid muscle and the masseter, extending from the mastoid tip to just below the angle of the mandible. A small tail projects from the inferior edge of the gland, separated by the submandibular space only by the stylomandibular ligament. From superficial to deep, the gland is superficial to the facial nerve, an area of crucial surgical relevance, followed by the retromandibular vein and the external carotid artery. Stensen’s duct, the main excretory duct of the PG, projects from the anterior portion of the gland over the masseter. In its trajectory, it pierces the buccinator muscle to open into the oral cavity at the level of the buccal mucosa of the second maxillary molar [4].

The submandibular gland (SMG), the second-largest gland, is about one-half the weight of the parotid and is found inferior to the mandible, between the anterior and posterior bellies of the digastric muscle. The SMG has a smaller anterior lobe and a larger posterior lobe. The lobes are connected in the posterior free edge of the mylohyoid muscle. The main excretory duct, referred to as Wharton’s duct, arises from the smaller, deep lobe inferior to the mucosa of the floor of the mouth to enter the oral cavity an open into the frenulum linguae at the sublingual caruncle. The hypoglossal nerve runs parallel and inferior to Wharton's duct [4].

The sublingual gland (SLG) lies beneath the mucosa of the floor of the mouth and superior to the mylohyoid muscle (between the mandible and genioglossus muscles). Medially, between the base of the tongue and the sublingual gland, the submandibular duct, and the sublingual nerve can be found. Rather than having one main duct, it contains a series of short ducts that project directly into the floor of the mouth, the ducts of Rivinus, and a common duct, known as Bartholin's duct that connects with the submandibular gland's duct at the sublingual caruncula [4][5][6][5].

While the major salivary glands produce 92% to 95% of saliva, the remainder is made by roughly 600 to 1000 minor salivary glands. They can be found in almost any part of the mouth (except for the gingiva and anterior part of the hard palate) but present most commonly in the lips, buccal mucosa, palate, and tongue. Each gland has exactly one duct, and although it contains both serous and mucous acini, their secretion is mainly mucous. Unlike the major salivary glands, they are not encapsulated by connective tissue but merely surrounded by it. Von Ebner glands, a subset of the minor salivary glands, are found surrounding the circumvallate papillae on the dorsal surface of the tongue. They secrete a serous fluid that helps with lipid hydrolysis and also plays a role in taste perception [1].

Architecture and Function

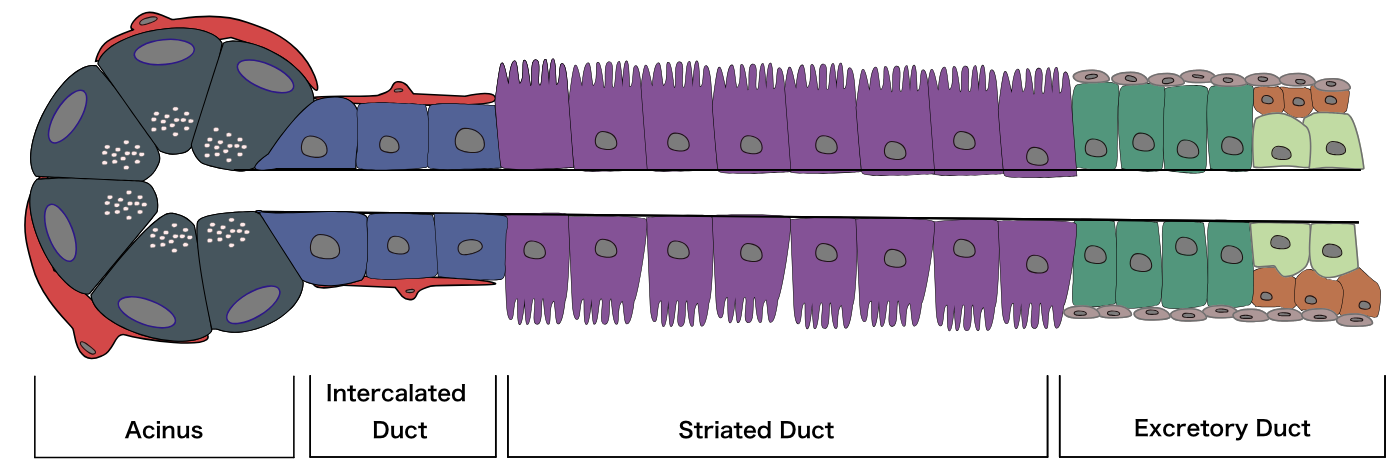

Salivary glands contain three major cell types: acinar cells, ductal cells, and myoepithelial cells. Despite their different locations, each of these glands shares the same fundamental structure, branched ducts that open into the oral cavity and glandular secretory end pieces, called acini, that produce saliva. Myoepithelial cells display 4 to 8 processes that wrap around the acini and intercalated ducts. They rhythmically contract to squeeze saliva from the acinar units through the duct system to release it into the oral cavity. In addition to myoepithelial cells, acinar cells are also surrounded by an extracellular matrix, immune cells, stromal cells, myofibroblasts, and nerve fibers [7].

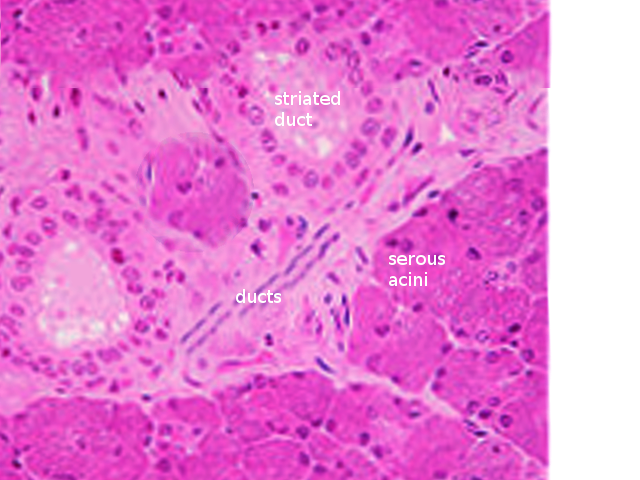

There are three main types of acini: serous, mucinous, and seromucous. Serous acini are relatively spherical and produce a watery secretion containing proteins modified and stored in secretory or zymogen granules, abundant at the cell's apex. In contrast to serous acini, mucinous acini store a significantly more viscous secretion rich in glycoproteins (or mucins), which becomes hydrated upon exocytosis to form mucus. Lastly, seromucous acini contain secretions of both types, although one kind of secretion may predominate. Each of the major salivary glands has different proportions of each acinus, affecting the composition of its secretions. The parotid contains serous acini and makes watery serous saliva. The submandibular and sublingual glands contain mucous and serous acini; therefore, they are known as mixed glands. The submandibular gland primarily presents serous acini, with only 10% of acini being mucinous. These mucinous acini contain crescent-shaped, serous demilune cells that wrap around the top of the cells. Similarly, the sublingual gland has mixed acini and demilunes but predominately mucinous acinar cells [8][6].

An integral function of the ductal system is modifying the electrolyte content of the secretion as it passes through the ductal system. Ductal structures are categorized and differentiated by their cellular composition, location, and function, forming three main types: the intercalated, striated, and excretory ducts. The intercalated ducts project directly from the acini and are formed by a single layer of cuboidal cells. Here, bicarbonate is secreted while chloride is absorbed from saliva. The intercalated ducts empty directly into the striated ducts, which are comprised of columnar cells with deep basolateral membrane invaginations that give it its characteristically striated appearance. These cells function mainly in reabsorbing sodium and adding potassium to the secretory product. The excretory duct has the largest diameter, and its epithelial lining is comprised of pseudostratified columnar cells. At this point, salivary fluid is relatively hypotonic to plasma because the rates of sodium and chlorine resorption are greater than that of potassium and bicarbonate secretion within the ducts. In addition, the luminal accumulation of ions within the ductal system creates an osmotic gradient responsible for the passive travel of water throughout the ducts [9][10].

Embryology

Salivary glands start developing at around 6 to 8 weeks of gestation when interactions between the epithelium and the adjacent mesenchyme initiate the thickening of the oral ectoderm. The glands develop via the process of branching morphogenesis of epithelium, involving systematic proliferation, clefting, differentiation, migration, cell death, and mesenchymal, epithelial, endothelial, and neuronal cell interactions. This branching process also occurs in other organ systems, including the lungs, kidneys, and mammary glands [11]. The terminal buds at the end of the branched ductal structures become acini at 14 weeks.

While the parotid gland is the first to begin its formation, the development of lymphatic tissue throughout the gland makes it the last of the glands to be enclosed in connective tissue and the only salivary gland with an enclosed lymphatic system. Human SMGs are well-differentiated by 13 to 16 weeks, featuring microvilli and desmosomes from cells near the lumens. The basal lamina surrounds the epithelium, and myoepithelial cells are thought to begin to appear at this stage. After 16 weeks, striated and intercalated ducts can be noticed. The glands stop developing at 28 weeks, marking the point at which acini produce secretory products. The glands are fully functional at birth [12][13].

Blood Supply and Lymphatics

Parotid Gland

The external carotid artery provides the blood supply to the parotid gland, which flows superiorly from the carotid bifurcation alongside the posterior aspect of the digastric muscle. This artery courses medially to the parotid, bifurcating into the superficial temporal artery, which runs superior to the parotid to the scalp, and the maxillary artery, which travels from the medial side of the parotid to carry blood to the infratemporal fossa and the pterygopalatine fossa. Lastly, the transverse facial artery branches off the superficial temporal artery, projecting anteriorly between the zygoma and parotid duct to provide blood to both the parotid gland and parotid duct, as well as the masseter muscle.

Blood from the maxillary vein and the superficial temporal vein join together to form the retromandibular vein, which runs through the parotid anterior to the facial nerve to join the external jugular vein. The retromandibular vein displays significant variation in its anatomy, and in some cases, splits into an anterior and posterior branch. The anterior branch can form a union with the posterior facial vein, forming the common facial vein. The posterior facial vein lies directly inferior to the marginal mandibular branch of the facial nerve and is often used as a landmark for pinpointing the nerve branch. By contrast, the posterior branch of the retromandibular vein can join with the post-auricular vein to drain into the external jugular vein [14].

The lymphatic system of the parotid gland differs from the other major salivary glands in that there is a high density of lymph nodes in and around it. In this way, it contains two nodal layers, draining into both the superficial and deep cervical lymph systems. Roughly 90% of the nodes are found in the superficial layer between the glandular tissue and capsule [15].

Submandibular Gland

Blood to the submandibular gland is supplied mainly from the facial artery, a branch of the external carotid artery. This artery runs medial to the posterior belly of the digastric muscle to project deep through the gland capsule before crossing the inferior margin of the mandible, referred to as the facial notch. After this point, it travels superiorly adjacent to the inferior branches of the facial nerve and into the face [16].

Unlike the parotid, the submandibular gland's pre-vascular and post-vascular lymph nodes are found between the gland and its fascia instead of being located within the glandular tissue. These nodes are closely associated with the facial artery and vein at the superior portion of the gland and exit into the deep cervical and jugular chains [16].

Sublingual Gland

The sublingual gland receives blood from the submental and sublingual arteries, which are branches of the lingual and facial arteries. While deoxygenated blood is carried away by veins parallel to the arteries mentioned above, drainage occurs predominantly through the submandibular lymph nodes [17].

Nerves

The salivary glands receive parasympathetic and sympathetic innervation. The parasympathetic innervation leads to serous salivary production and ion secretion, and the sympathetic increases the secretion of proteins. The sympathetic innervation is also known to regulate the blood flow of the glands and local inflammatory and immune mediators [18][19].

The parotid gland is innervated via the glossopharyngeal nerve (CN IX). The parasympathetic cell bodies that innervate the parotid gland are located in the otic ganglion. Postganglionic fibers from the otic ganglion then join the auriculotemporal nerve to innervate the parotid. The submandibular ganglion, located within the SMG and adjacent to the lingual nerve, contains the cell bodies of parasympathetic fibers that innervate the SMG and SLG, as well as their myoepithelial cells [20]. The preganglionic parasympathetic fibers of the SMG and SLG originate in the superior salivatory nucleus in the pons, eventually joining with the facial nerve (CN VII). These fibers pass through the chorda tympani, leave the skull through the petrotympanic fissure, and join with the lingual nerve, which runs directly adjacent to Wharton’s duct, to finally synapse in the submandibular ganglion [19]. By contrast, the cell bodies of the sympathetic fibers are found in the superior cervical ganglion in the neck, where postganglionic fibers innervate the glands along blood vessels branching off of the carotid plexus. Finally, the preganglionic fibers originate in the thoracic ganglion, ascending through the spinal cord [20].

Secretions by the minor salivary glands are not regulated by neuronal control like the major glands are. Instead, they continuously secrete small amounts of saliva, even at night when the major glands are resting, resulting in sustained lubrication to oral surfaces [21].

Physiologic Variants

Around 20% of individuals have accessory parotid tissue extending to the anterior masseter muscle. This is often confused with a mass when taking a positron emission tomography. Other anatomic variants of the parotid include unilateral and bilateral aplasia, parotid duct duplication, and parotid duct fistulas, characteristic of branchial cleft anomalies. Accessory tissue is histologically distinguished from normal parotid because it contains mucinous acinar cells and serous acinar cells [22].

Surgical Considerations

Identifying the facial nerve is essential when excising and resecting the parotid and submandibular gland to prevent further complications [23]. In the case of parotidectomies, the goal of the surgery is centered on carefully removing the tumor and the associated tissue margins of the gland and protecting the function of the facial nerve. Some anatomical landmarks for identifying the facial nerve are more effective than others. For example, the posterior digastric muscle and the tragal pointer are less reliable due to their variability or difficulty to localize. By contrast, bony landmarks are the most dependable and safest, such as the tympanomastoid fissure. Other methods for localizing the nerve trunk include retrograde tracing of its distal branches proximally [23].

Compared to the parotid, removing the submandibular gland and sublingual gland is more straightforward, but it requires a deep understanding of the anatomy of the mouth floor and the neck [24]. Since the lingual nerve is in close connection with Wharton's duct, lingual nerve injury is a common complication of the surgical removal of stones in shialolithiasis [6].

Clinical Significance

General Considerations

When assessing a patient with a dysfunction of the salivary glands, one must consider that it is often associated with other systemic disorders, such as hormonal imbalances, diabetes mellitus, arteriosclerosis, and neurologic conditions. Xerostomia (the symptom of dry mouth) and sialorrhea (increased salivary flow) can be caused by the dysfunction of the medullary salivary center, autonomic innervation to the glands, damage to the glands itself, or imbalances in fluid and electrolytes [25].

Considering drug history is also important, as xerostomia is a side effect of many medications, such as stimulants and antihypertensive drugs [25].

Gender and age are also influential factors in the development of salivary gland conditions. For example, Sjogren syndrome, an autoimmune disorder common that causes xerostomia, is common in menopausal women. Other symptoms of the disease include dry eyes, dry skin, arthritis, and fatigue. Natural aging leads to more viscous saliva via reduced ptyalin and mucin production and therefore changes saliva composition rather than the quantity.

Tumors of the salivary glands are common, and radiation therapy from head and neck cancer should be noted, as they often cause persistent xerostomia due to damage to the acini [25].

When treating dry mouth, sialogogic agents (sialogogues), such as pilocarpine and cevimeline, are effective options. Pilocarpine non-selectively stimulates muscarinic receptors that enhance secretions of the salivary and lacrimal glands. Other treatments include topical sialogogues and saliva substitutes, which aim to replace saliva and offer improved mucosal lubrication [26].

Sleep-related xerostomia refers to the sensation of dry throat and mouth leading to sleep disruption due to the need of consuming water [27].

Pathologies

Technetium 99m pertechnetate (TPT) scans of the head and neck are a useful diagnostic tool for salivary glands pathologies. The rate of salivary flow, xerostomia, and sialectasis (cystic dilation of the ducts) are associated with reductions in TPT uptake by the glands. These scans are also helpful for discriminating between different varieties of salivary tumors and identifying their relative size [28].

Sialadenitis, or inflammation of the salivary gland, can be caused by infection, irradiation, allergies, or trauma. Common infections include mumps, a viral sialadenitis that occurs predominantly in children. Symptoms include pain in front of the ear, parotid swelling, chills, headaches, and fever. Moreover, reduced oral cavity protection to bacteria due to xerostomia results in higher indices of gland infection thanks to increased numbers of microorganisms [29].

Sialolithiasis is a common condition referring to the formation of calcified salivary stones, or sialoliths, within the gland. They usually form in excretory ducts, the most common of which is Wharton’s duct, but are also seen in the parotid, sublingual, and minor salivary glands. The blockage usually leads to pain, swelling, and inflammation of the gland, all of which are exacerbated upon increases in salivary flow. In more severe cases, symptoms include pus, infection, and bad breath. While the mechanism of stone formation is not well understood, it is thought to result from aberrant calcium metabolism, dehydration, changes in pH due to infections, and xerostomia [30][31][32].

A traumatic injury can cause the formation of mucoceles, a tearing of the salivary gland resulting in spillage of mucins into the surrounding tissue. It manifests itself as a bluish swelling and typically appears on the lower lip. In addition, a mucocele of the sublingual gland, known as a ranula, occurs on the floor of the mouth. Ranulas are relatively larger than mucoceles. In rare circumstances, they have been known to descend into the neck receiving the name of “plunging” ranulas. Usually, ranulas are asymptomatic, but they must be excised if they are large enough [33].