Introduction

The conjunctiva of the eye provides protection and lubrication of the eye by the production of mucus and tears. It prevents microbial entrance into the eye and plays a role in immune surveillance. It lines the inside of the eyelids and provides a covering to the sclera. It is highly vascularized and home to extensive lymphatic vessels.

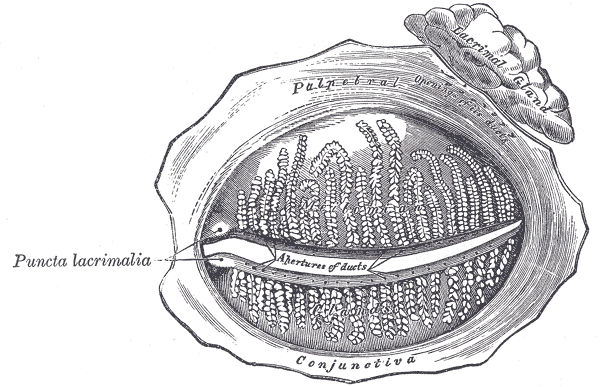

The conjunctiva can be divided into three regions: the palpebral or tarsal conjunctiva, the bulbar or ocular conjunctiva, and the conjunctival fornices. The palpebral conjunctiva is further divided into the marginal, tarsal, and orbital regions. The bulbar conjunctiva is divided into scleral and limbal parts. Finally, the conjunctival fornices are divided into the superior, inferior, lateral, and medial regions. The palpebral conjunctiva lines the eyelids. The bulbar conjunctiva is found on the eyeball over the anterior sclera. Tenon's capsule binds it to the underlying sclera. The potential space between Tenon’s capsule and the sclera is frequently used for local anesthesia. The conjunctiva has an average thickness of 33 microns. Lastly, the conjunctival fornices form the junction between the palpebral and bulbar conjunctivas. This protective covering is loose and flexible, unlike its bulbar counterpart, allowing for movement of the globe and eyelids.

The conjunctiva of the eye consists of an epithelial layer composed of stratified squamous and stratified columnar epithelium. It is non-keratinized with interspersed goblet cells. There are also present within this epithelial layer blood vessels, fibrous tissue, lymphatic channels, melanocytes, T- and B-cell lymphocytes, Langerhans cells, and accessory lacrimal glands. A deeper layer, the substantia propria or conjunctival submucosa, consists of superficial lymphoid and fibrous tissue. The substantia propria is a tissue layer that only exists in the conjunctiva, but not in other eye tissues. Numerous lymphocytes, mast cells, plasma cells, and neutrophils are present within this connective tissue layer. Finally, the deepest fibrous layer contains the nerves and vessels providing innervation and blood supply to the conjunctiva. Also located within this deep layer are the glands of Krause. [1][2]

The conjunctival epithelium has a thickness of 3 to 5 cell layers thick. The basal cells of the epithelium are cuboidal and become more flattened as they approach the surface.

In the area closest to the fornix, the conjunctiva has the greatest number of goblet cells. These unicellular mucous glands are especially common in the inferior and medial conjunctiva and near the medial canthus. Away from the fornix, the number of goblet cells decreases. Additionally, the fornix has a greater number of patches of lymphocytes, which are mostly suppressor T-cells. There are patches of immune cells such as T and B lymphocytes that form conjunctiva-associated lymphoid tissue (CALT). [2]

Structure and Function

The conjunctiva covers the anterior, non-corneal portions of the globe, as well as the fornices and the palpebrae. The conjunctival epithelium has multiple functions. In addition to serving as a physical barrier, the conjunctiva’s goblet cells secrete mucin, which forms a part of the tear film of the eye. This allows for the ocular surface to maintain its healthy moisture layer. The conjunctiva also has some immune cells that aid in the defense of the ocular surface. [3]

Embryology

The conjunctiva develops from the ocular surface ectoderm. This is the same origin of all other epithelia of the eye, including the cornea and the limbus.[4]

Blood Supply and Lymphatics

The conjunctiva receives its blood supply from the marginal tarsal arcades, peripheral tarsal arcades, and the anterior ciliary arteries. The marginal tarsal arcades provide blood supply to the palpebral conjunctiva along with the fornices. The proximal arcade lies along the upper border of the lid, feeding the forniceal conjunctiva and then becoming the posterior conjunctival arteries that feed the bulbar conjunctiva. The anterior ciliary arteries supply the bulbar conjunctiva and are derived from the ophthalmic artery. Further, there is connectivity between the blood supplies of the conjunctiva, so ultimately, overlap exists between the blood supply from both of the larger vessels to the conjunctiva to some extent. The watershed area of the anterior ciliary arteries, which supply the conjunctiva at the limbus, and the posterior conjunctival arteries, which travel from the posterior bulbar conjunctiva anteriorly, lie about 3 to 4 mm from the limbus.[5][6]

Nerves

The conjunctiva receives sensory innervation from the supraorbital nerve, the supratrochlear nerve, the infratrochlear nerve, the infraorbital nerve, the lacrimal nerve, and the long ciliary nerves. The superior portion is supplied by the supraorbital nerve, the supratrochlear nerve, and the infratrochlear nerve. The infraorbital nerve supplies the inferior portion. Finally, the lateral portion is supplied by the lacrimal nerve, while the long ciliary nerves supply the circumcorneal portion.[7]

Muscles

There are no muscles that originate or insert directly into the conjunctiva. Instead, some muscles interact with parts of the eye near the conjunctiva. For example, the layers of the eyelid from superficial to deep include the skin, orbicularis oculi muscle, the tarsus, and then the palpebral conjunctiva. The extraocular muscles of the eye, such as the four rectus muscles (superior, inferior, medial, and lateral recti), insert on the globe at various distances, posterior to the limbus. These muscle insertions lie deep to the bulbar conjunctiva.

Physiologic Variants

Conjunctivochalasis refers to redundant conjunctiva, typically involving the inferotemporal conjunctiva. This can be asymptomatic in some individuals. It is a normal physiologic variant with incidence increasing with age. However, the redundant conjunctiva can be associated with symptoms of dry eye syndrome. Some postulate that normal tear meniscus formation is impaired and that normal tear movement is blocked. Nevertheless, no definitive pathologic mechanism has been discovered for this association. [8][9]

Surgical Considerations

There are many routine procedures that involve the conjunctiva. In conjunctivochalasis, described above, the conjunctiva is grasped with forceps and thermocautery is used to cause contraction of the redundant tissue.[10]

Clinical Significance

The surface of the eye is exposed to numerous external influences. It is susceptible to many disorders including dryness, allergic reactions, chemical irritation, trauma, and infections. Many systemic illnesses result in irritation to the conjunctiva. Sickle-cell anemia, type II diabetes mellitus, hypertension, carotid artery occlusion, and leptospirosis are just a few diseases that result in changes to the blood supply or the structure of the conjunctiva.

The bulbar conjunctiva can generally be assessed at the slit lamp by having the patient look nasally to assess the temporal conjunctiva, and temporally to assess the nasal conjunctiva. The superior and inferior portions of the bulbar conjunctiva may be assessed by gently holding the patient’s eyelid open while the patient looks up or down. The palpebral conjunctiva and fornices may be more difficult to assess but may be assessed using a small cotton swab to invert the lid.

The conjunctiva can be assessed clinically using common stains at the slit-lamp by a trained ophthalmologist. A small amount of fluorescein dye is applied to the ocular surface, and light with a blue filter is used to detect areas of increased stain uptake, indicative of damaged epithelium. Lissamine green and Rose Bengal can also be used to stain the ocular surface with appropriate absorption filters. While both Lissamine green and Rose Bengal have similar staining characteristics, Lissamine green is better tolerated by patients and is thus more frequently used in the clinical setting. Various methods exist for grading abnormalities, including the Oxford grading scale and the National Eye Institute (NEI) scales. Both of these scales are developed for grading the conjunctiva and the cornea.[11][12]