Continuing Education Activity

Neurotrophic keratitis, formerly known as neuroparalytic keratitis, is a degenerative corneal disease characterized by decreased or absent corneal sensation, leading to epithelial breakdown, impairment of healing, and ultimately corneal ulceration, melting and perforation. This activity describes the etiology, evaluation, and management of neurotrophic keratitis and highlights the role of the interprofessional team in the care of affected patients.

Objectives:

- Identify the etiology of neurotrophic keratitis.

- Describe the presentation of neurotrophic keratitis.

- Outline the treatment and management options for neurotrophic keratitis.

- Explain interprofessional team strategies for enhancing coordination and communication to advance the treatment and management of neurotrophic keratitis and improve patient outcomes.

Introduction

Neurotrophic keratitis is a degenerative corneal disease caused by impairment of corneal sensory innervation. It is characterized by decreased or absent corneal sensation, leading to epithelial breakdown, impairment of healing, and ultimately to the development of corneal ulceration, melting and perforation.[1] This condition was initially described as neuroparalytic keratitis: Magendie demonstrated this condition experimentally in 1824.

Etiology

Ocular and systemic conditions associated with damage at any level to the fifth cranial nerve, from the Trigeminal nucleus to the corneal nerve endings may lead to the development of neurotrophic keratitis. The most common causes include herpetic keratitis, chemical burns, long-term use of contact lenses, corneal surgery, ablative procedures for trigeminal neuralgia, and surgical procedures for reduction of jaw fractures. Other less frequent causes are space-occupying intracranial masses (e.g., schwannoma, meningioma and aneurysms) that can lead to compression of the nerve and reduce corneal sensitivity. Systemic diseases that may compromise trigeminal function like diabetes, multiple sclerosis and Leprosy may lead to the development of neurotrophic keratitis. Presence of neurotrophic keratitis in children is rare and may be seen in association with congenital syndromes like Riley-Day syndrome, Goldenhar- Gorlin syndrome, Mobius syndrome, Familial corneal hypesthesia and Congenital Insensitivity to Pain with Anhidrosis[2]

Epidemiology

Neurotrophic keratitis is considered to be a rare disease with an estimated prevalence of less than 5/10,000. It is estimated that neurotrophic keratitis affects 6% of herpetic keratitis cases, 12.8% of Herpes zoster keratitis cases and 2.8% of patients who underwent surgical procedures for Trigeminal neuralgia.

Pathophysiology

Corneal nerves play an important role in maintaining corneal epithelial integrity, proliferation and wound healing. It has been postulated that corneal sensory nerve damage leads to marked changes in levels of neuromodulators, that cause impairment in epithelial cell vitality and metabolism of the epithelial cells. This can affect mitosis of epithelial cells and consequently lead to an epithelial breakdown. There is an associated reduction in lacrimation reflex with sensory nerve involvement, which can worsen the damage. The corneal epithelium thickness is decreased, and epithelial cells show intracellular swelling, loss of microvilli, and an abnormal production of the basal lamina. The resulting morphological and metabolic epithelial disturbances lead to the development of recurrent or persistent epithelial defects, which can progress to corneal ulceration, melting and perforation. A large number of chemical mediators have been postulated to play a role in the development of neurotrophic keratitis including nerve growth factor, Substance P, neuropeptide Y, Calcitonin gene-related peptide, Galanin, and Acetylcholine.

History and Physical

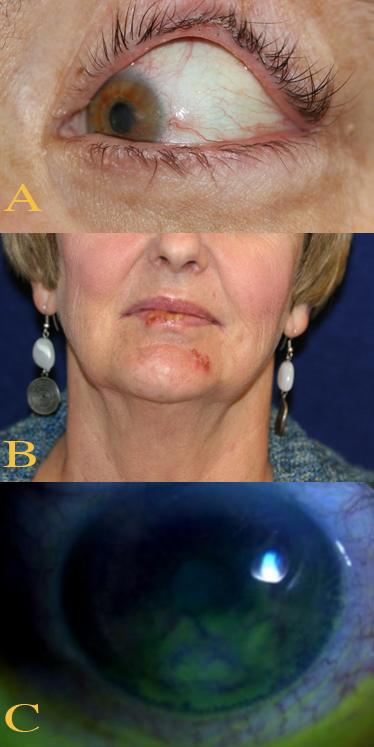

Patients with Neurotrophic keratitis rarely complain of symptoms, probably due to their lack of corneal sensation. Occasionally, however, they may present with redness and blurring of vision. The blurring of vision can occur due to persistent epithelial defects, corneal edema, or scarring. Antecedent episodes of redness and eye pain or the presence of cutaneous blistering or scarring suggest previous herpetic infections. A history of corneal trauma, surgery, chemical burns, long-term use of topical medications, neurosurgical procedures, or diabetes may be obtained.

The hallmark of this disease is reduced or absent corneal sensation. Neurotrophic keratitis can be classified into three stages according to the Mackie classification. This staging is based on the severity of corneal damage, increasing from stage 1 to stage 3.

- Stage 1 is characterized by corneal epithelial changes with dry and cloudy corneal epithelium, the presence of superficial punctate keratopathy, and corneal edema.

- Stage 2 is characterized by recurrent and/or persistent epithelial defects with an oval or circular shape, most frequently localized at the superior half of the cornea.

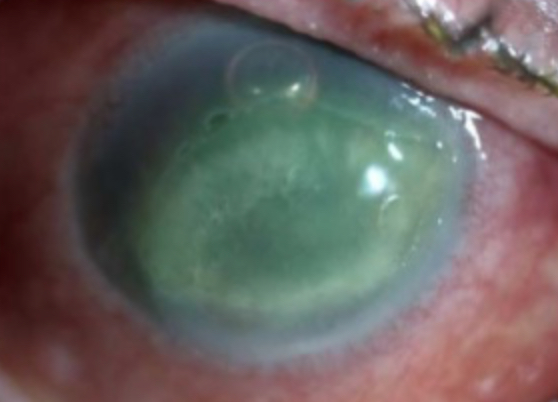

- Stage 3 is characterized by corneal ulcer with stromal involvement that may be complicated by stromal melting and progression to corneal perforation.

In summary, staging of neurotrophic keratitis is characterized by epithelial changes (stage 1), persistent epithelial defects (stage 2), and corneal ulcer (stage 3).

Evaluation

The diagnosis is frequently suspected by the patient’s history associated with trigeminal impairment, presence of persistent epithelial defects or ulcers, and decreased corneal sensitivity. [3]The presence of systemic diseases (such as Diabetes Mellitus), medication use (like neuroleptics), and corneal causes (like contact lens abuse, chemical burns, etc. ) must be evaluated. Clinical evaluation of different cranial nerve functions may help in localization of the site of the lesion. Associated seventh or eighth nerve palsy may be an indication of acoustic neuroma or its surgical resection causing trigeminal nerve damage. Associated third, fourth, and sixth nerve palsy may point to a cavernous sinus pathology.

Assessment of the cornea includes a quantitative evaluation of decreased corneal sensation using a Cochet-Bonnet or no-contact gas esthesiometer.

Slit lamp examination can be of great help for identifying the characteristic corneal lesions and for sector iris atrophy, which is characteristic of herpetic infections. An ulcer, if seen, requires microbiological examination to rule out an infection.

Dilated fundus examination may reveal pale or swollen optic disc in cases of intracranial tumors with trigeminal compression. Tear film function should be evaluated because decreased corneal sensitivity may alter the tear film and trigger a vicious circle in which tear film dysfunction worsens the prognosis of neurotrophic keratitis. The eyelids need to be examined, both for diagnostic and prognostic reasons. Lagophthalmos would exacerbate the changes see

- Bacterial keratitis

- Corneal mucus plaques

- Dry eye disease

- Herpes simplex virus keratitis

- Herpes simplex virus in emergency medicine

- Herpes zoster

- Keratoconjunctivitis

- Postoperative corneal melt

- Sjogren syndrome

n in neurotrophic keratitis.

Treatment / Management

Early diagnosis, treatment and careful monitoring of neurotrophic keratitis patients are mandatory to achieve epithelial healing and prevent progression of corneal damage.

The use of preservative-free artificial tears may help improve the corneal surface at all stages of disease severity.

In the event of stromal melting, use of topical collagenase inhibitors, such as N-acetylcysteine, and systemic administration of tetracycline or medroxyprogesterone may be considered. Use of topical antibiotic eye drops to prevent infection in eyes with neurotrophic keratitis at stages 2 and three are recommended. Topical nerve growth factor (NGF) and autologous serum eye drops are considered as promising treatments of neurotrophic keratopathy.[4]

Surgical treatments are reserved for refractory cases. They include partial or total tarsorrhaphy, amniotic membrane transplantation, conjunctival flap, and Botulinum A toxin injection of the eyelid elevator muscle.

- Stage 1 neurotrophic keratitis is mainly managed with preservative-free artificial tears.

- Stage 2 with conjunctival flap and partial tarsorrhaphy for the persistent epithelial defects.

- Stage 3 with therapeutic contact lenses and amniotic membrane transplantation.Corneal perforations may be managed with cyanoacrylate glue application, conjunctival flap or lamellar/penetrating keratoplasty.

Neurotization surgery with direct transfer of the supratrochlear or supraorbital nerves to the subconjunctival space has shown promise. [5][6][7][8]

Differential Diagnosis

- Herpes simplex virus keratitis

- Herpes simplex virus in emergency medicine

- Postoperative corneal melt

Pearls and Other Issues

The prognosis of neurotrophic keratitis depends on the cause and severity of the trigeminal damage and the presence of associated ocular surface disease. It is accepted that the more severe the corneal sensory impairment, the higher the probability of neurotrophic keratitis progression. All the current therapeutic approaches focus on preventing the disease progression, but there are none to improve the corneal sensation and visual acuity. However, use of topical nerve growth factor derivatives and an Ergoline derivative, called Nicergoline are promising approaches in improving corneal sensation and thus extremely beneficial in patients who fail to respond to conventional therapy.[9]

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Neurotrophic keratitis is best managed by an interprofessional team that also includes the ophthalmology nurse.

Clinicians should be aware that patients with neurotrophic keratitis rarely complain of symptoms, probably due to their lack of corneal sensation. Occasionally, however, they may present with redness and blurring of vision. The blurring of vision can occur due to persistent epithelial defects, corneal edema, or scarring. Antecedent episodes of redness and eye pain or the presence of cutaneous blistering or scarring suggest previous herpetic infections. History of corneal trauma, surgery, chemical burns, long-term use of topical medications, neurosurgical procedures, or diabetes may be obtained. Once the disorder is suspected, a prompt referral to an ophthalmologist is necessary.

Early treatment can help prevent the worsening of the corneal injury.