Introduction

Vertebrae, along with intervertebral discs, compose the vertebral column or spine. It extends from the skull to the coccyx and includes the cervical, thoracic, lumbar, and sacral regions. The spine has several major roles in the body that include: protection of the spinal cord and branching spinal nerves, support for the thorax and abdomen and allows for flexibility and mobility of the body. The intervertebral discs are responsible for this mobility without sacrificing the supportive strength of the vertebral column.

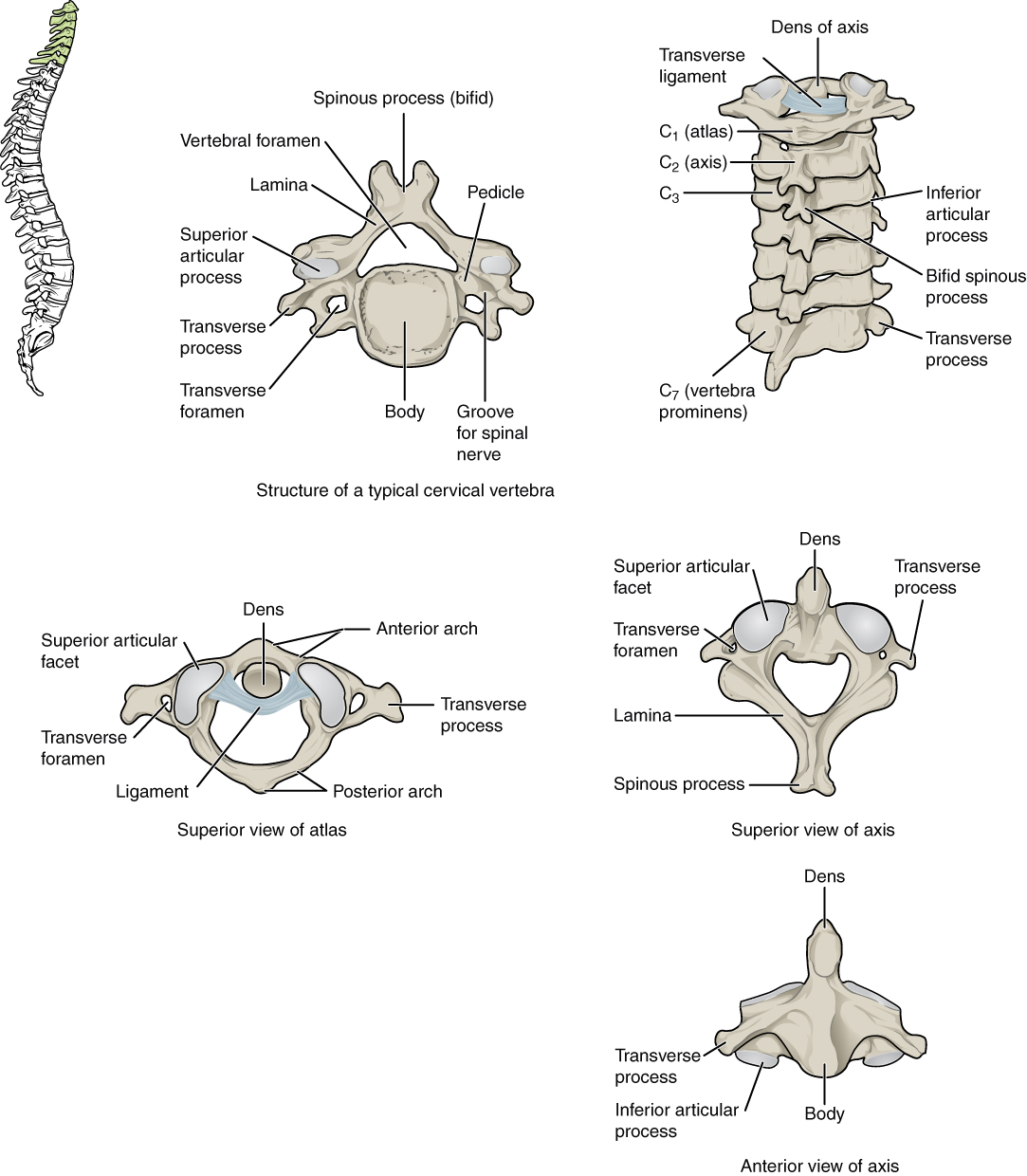

The cervical region contains seven vertebrae, denoted C1-C7, which are the smallest of the vertebral column. The intervertebral discs, along with the laminae and the articular processes of adjacent vertebrae, create a space through which spinal nerves exit. The cervical vertebrae, as a group, produce a lordotic curve. While all vertebrae share most morphologic features, several notable features exist in the cervical region.[1][2]

Typical vertebrae consist of a vertebral body, a vertebral arch, as well as seven processes. The body bears the majority of the force placed on the vertebra. Vertebral bodies increase in size from superior to inferior. The vertebral body consists of trabecular bone, which contains the red marrow, surrounded by a thin external layer of compact bone. The arch, along with the posterior aspect of the body, forms the vertebral (spinal) canal, which contains the spinal cord. The arch consists of bilateral pedicles, cylindrical processes of bone that connect the arch to the body, and bilateral lamina, flat bone segments that form most of the arch, connecting the transverse and spinous processes.

A typical vertebra also contains four articular processes, two superior and two inferior, which contact the inferior and superior articular processes of adjacent vertebrae, respectively. The point at which superior and articular facets meet is known as a facet, or zygapophyseal, joint. These maintain vertebral alignment, control the range of motion, and are weight-bearing in certain positions. The spinous process projects posteriorly and often inferiorly from the vertebral arch and may overlap the inferior vertebrae to various degrees, depending on the region of the spine. Lastly, the two transverse processes project laterally from the vertebral arch symmetrically.

Typical cervical vertebrae have several features distinct from those typical of thoracic or lumbar vertebrae. The most notable distinction is the presence of one foramen in each transverse process. These transverse foramina encircle the vertebral arteries and veins. This is true of all cervical vertebrae except C7, whose transverse foramina contain only accessory veins. Another feature unique to the cervical vertebrae is the bifid spinous process (See “physiologic variants” section), which may increase the surface area for muscle attachment. The spinous process of cervical vertebrae increases as the spinal column descends. Cervical vertebrae tend to have superior articular facets that face posteromedially. Some studies have shown that more inferior cervical vertebrae have superior facets that face in a posterolateral direction – more akin to those of the thoracic region. Lastly, cervical vertebrae are known to have the greatest intervertebral disc height, which increases the range of motion.

There are three atypical vertebrae found in the cervical region. C1, also known as “atlas,” is unique among all vertebrae in that it lacks both a vertebral body and a spinous process. The relatively circular bone contains two bilateral masses that take the place of a body in its load-bearing capacity. The superior articular facets of these masses contact the occipital condyles of the skull, and the inferior facets articulate with superior facets of C2. C2, also known as “axis,” is distinct in that it contains bilateral masses to articulate with C1, a body through which weight is transmitted through C3 and below, and an odontoid process, or “dens,” on the superior aspect of the body. The dens articulates with the posterior surface of the anterior arch of C1. C7 may be considered typical or atypical but has two distinct features. The first is that, unlike the rest of the cervical vertebrae, the vertebral artery does not traverse the transverse foramen. The second is that it contains a long spinous process known as “vertebra prominens.”[3]

Structure and Function

As with all physiology, the anatomy of a structure is related directly to its function. The smaller size of cervical vertebrae relative to the other regions reflects their decreased load-bearing requirements. Their decreased size allows for the greatest range of motion of all vertebral segments. The transverse and spinous processes serve as points of attachment and leverage for cervical and upper thoracic musculature. Atlas has the lowest load-bearing requirement of all vertebrae, which accounts for its small size and lack of vertebral body.

The absence of the body and the positioning of the lateral masses allows for the majority of cervical flexion and extension (motion in the sagittal plane) to occur through the atlantooccipital joint. The dens of C2 serve as an axis around which C1 rotates. This allows for the rotation of the head in the transverse plane. Due to the size of the intervertebral discs and the orientation of the facet joints, the cervical region has the greatest flexion ability of the spinal column.

Ligaments of the Vertebral Column

The anterior longitudinal ligament lies anterior to the bodies of the vertebrae and intervertebral discs. It passes from the base of the skull to the sacrum. It is strong and helps to prevent anterior protrusion of a herniated intervertebral disc.[4]

The posterior longitudinal ligament lies within the vertebral column posterior to the vertebrae. It connects the intervertebral discs from C2 to the sacrum.[5] The lack of attachment to the C1 vertebra can be correlated with the lack of an intervertebral disc for the atlas. The posterior longitudinal ligament continues into the foramen magnum as the tectorial membrane. The tectorial membrane is tightly attached to the clivus, passing over the atlantoaxial joint to attach strongly to the axis. Evaluation of the tectorial membrane by imaging studies is an important part of the evaluation for patients with possible traumatic craniovertebral dislocation.[6]

The posterior longitudinal ligament prevents the direct posterior dislocation of the nucleus pulposus of a herniated intervertebral disc. Instead, the herniated nucleus pulposus will pass lateral to the posterior longitudinal ligament. The posterior longitudinal ligament is richly supplied with nociceptive fibers that help to account for the pain of a herniated intervertebral disc. These are associated with the meningeal branch of each spinal nerve.[7]

The posterior longitudinal ligament can undergo ossification. The development of this condition is associated with irreversible severe cervical paralysis. Risk factors are female gender and obesity.[8] Genetic factors may play a role as well.[5]

Each zygapophyseal joint has a joint capsule. The cervical joint capsules are especially thin, allowing increased movement of these cervical joints.

The ligamenta flava are formed from thin connective tissue bands that connect adjacent laminae. These are especially thin, long, and broad in the cervical region. As one passes caudally down the vertebral column, they become broader and stronger. They are composed of elastic tissue. They resist the separation of the laminae during flexion of the vertebral column.

The interspinous ligaments serve to join the spinous processes.[9]

In the cervical region, they join with the ligamentum nuchae. This fibroelastic ligament connects the base of the skull with the cervical vertebrae.[10]

The first cervical vertebra (atlas) is connected to the base of the occipital bone. This joint permits flexion and extension of the head (as in nodding yes), as well as lateral flexion and rotation.

The ligaments that stabilize the craniovertebral joint consist of the alar and apical ligaments, the cruciate ligament, and the tectorial membrane.[6] The atlas and the cranium are connected by the atlanto-occipital membranes, which help prevent excessive movements of the joint. The transverse ligaments of the atlas connect to the tubercles of the lateral aspects of the atlas. The addition of vertical bands to the transverse ligaments constitutes the cruciate ligament of the atlas. The alar ligament passes from the dens to the lateral aspects of the foramen magnum. These ligaments act to help absorb shock.[11][12]

Ligamentous injury is an important part of cervical trauma, such as whiplash injury.[13]

Herniated intervertebral discs can occur in the cervical region, although they are more common in the lumbar region. Herniated cervical discs can be dangerous because the nucleus pulposus can compress the spinal roots that innervate the back and upper limbs.

Vertebral bone marrow edema can correlate with herniated intervertebral discs, although their role is controversial.[14]

Embryology

All vertebrae begin ossification in the embryonic development period around eight weeks of gestation. They ossify from three primary ossification centers: one in the endochondral centrum (which will develop into the vertebral body) and one in each neural process (which will develop into the pedicles). This begins at the thoracolumbar junction and proceeds in the cranial and caudal directions. The neural processes fuse with the centrum between three and six years of age.

During puberty, five secondary ossification centers develop at the tip of the spinous process, both transverse processes and on the superior and inferior surfaces of the vertebral body. The ossification centers on the vertebral body are responsible for the superior-inferior growth of the vertebrae. Ossification ends around the age of 25.

Blood Supply and Lymphatics

The cervical vertebrae are supplied by the vertebral and ascending cervical arteries. These main arteries branch out into the periosteal and equatorial arteries, which in turn branch into anterior and posterior canal branches. Anterior vertebral canal branches send nutrient arteries into the vertebral body to supply the red marrow.

Nerves

The meningeal branches of spinal nerves innervate all vertebrae.

Muscles

Cervical vertebrae provide points of attachment for numerous muscles, including erector spinae, interspinales, intertransversarii, levator scapulae, multifidus, obliquus capitis, rectus capitis, rhomboid minor, rotatores, semispinalis, splenius capitis, and trapezius.

Physiologic Variants

The bifid spinous process, while unique to cervical vertebrae, is not found in all cervical vertebrae of all individuals. While the numbers vary by study, it has been demonstrated that only C2-C4 consistently has bifid spinous processes. The prevalence decreases as one continues down the spinal column, with C7 having the lowest likelihood of being bifid (0.3% of the population.) This is significant as it discredits the practice of using bifid spinous processes to orient oneself during surgery.[15][16]

The only intervertebral space in the spine that does not contain an intervertebral disc is between C1 and C2.

Surgical Considerations

The position of the foramen transversarium is critical due to its content being the vertebral artery. This is of utmost importance while placing the posterior lateral mass screws in the subaxial cervical spine and during transarticular screw implantation for atlantoaxial fixation, as a misdirection of the screw can injure the vessel, which may result in significant neurological deficits and catastrophic bleeding.

Clinical Significance

Atlas fractures comprise a small fraction of all vertebral spine fractures (approximately 2%). They tend to occur when the skull is forced in an inferior direction. It is known as a Jefferson fracture when the atlas fractures at the anterior and/or posterior arches, the weakest points. In a Jefferson fracture, the transverse ligament may be damaged. This ligament extends from one lateral mass of the atlas to the other, passes between the dens and the spinal cord, and stabilizes the articulation of the dens on the axis. A Jefferson fracture requires cranial traction and immobilization. Fractures and damage to the transverse ligament require an immediate fusion of cervical vertebrae via occipital-cervical arthrodesis to prevent spinal cord injury.[17]

Odontoid process fracture may occur via hyperflexion, with or without anterior deviation of the dens and atlas, or hyperextension, with or without posterior deviation of the dens and atlas. These make up 5% to 15% of cervical spine fractures.

Hangman fracture is a bilateral spondylolisthesis of C2, resulting from hyperextension-distraction, in which the pedicles of C2 are fractured, and the body of C2 is displaced from its position on C3. The Levine and Edwards classification of this fracture describes four subtypes of this injury. This fracture is poorly named as it is rarely found in those who have been hanged and, most commonly, is found in victims of automotive collisions.

Cervical spondylosis is a broad term that refers to a degenerative disease of the spine, intervertebral discs, ligaments, and cartilage. This disease is common in individuals over 40 years of age, and the main risk factors are age and occupation. This disease process is significant in that it dramatically increases the likelihood of cervical radiculopathy, the compression of nerve roots, and cervical spondylotic myelopathy, the compression of the spinal cord.

Electromyography and nerve conduction studies may determine the severity of nerve damage, while MRI is used to detect bone, spinal cord, and intervertebral disc abnormalities. Depending on the severity, both conditions may be treated either conservatively with anti-inflammatory medication and physical therapy or with corrective surgery.