Continuing Education Activity

Osteochondral autografts can be used to treat full-thickness cartilage defects. There are numerous treatment options for patients with focal cartilage defects. This activity reviews the evaluation and treatment of osteochondral defects with osteochondral autografts and highlights the role of the interprofessional team in evaluating and treating patients who undergo this procedure.

Objectives:

- Identify the anatomical structures involved in osteochondral autograft transplantation.

- Describe the equipment, personnel, preparation, and technique in regards to osteochondral autograft transplantation.

- Review the appropriate evaluation of the potential complications and their clinical significance in osteochondral autograft transplantation.

- Discuss interprofessional team strategies for improving care coordination and communication to advance osteochondral autograft transplantation and improve outcomes.

Introduction

There have been different procedures described for the treatment of cartilage defects. When the defect is full thickness, the chances of “self-repair” are small.[1] Historically, micro-fracture surgery has been utilized for smaller defects. However, this promotes healing through the formation of fibrocartilage, which is not ideal in the setting of repetitive weight-bearing and compressive forces, which can be detrimental to the joint over time and linked to worse patient outcomes.[2][3]

Other procedures utilizing autologous cells have been described. Autologous chondrocyte implantation, a procedure involving placement of cultured chondrocytes into the defect and sutured into place, has been described downfall being the technically demanding nature of the procedure; however, it can be a good option for larger lesions. Osteochondral autograft transplantation can consist of a single plug or multiple plugs used to fill a larger defect.[4]

The use of multiple plugs to fill a defect is termed mosaicplasty.[5] The single plug technique requires the donor surface architecture to be similar to the recipient site for the procedure to be successful.[6] With mosaicplasty, the donor site architecture can be less congruent since multiple donor plugs are placed into the defect. The spaces between the multiple plugs will fill with fibrocartilage. In the past, articular cartilage lesions have been treated by subchondral bone abrasions or drilling at the site of focal damage. For osteochondral lesions, bulk autografts and allografts[7][8] have been used. But these are reserved for massive lesions, which are larger than 10 cm2.[9][10]

Autogenous or allogenic osteochondral plugs have become popular due to the following reasons:

- They can be performed in a single procedure.

- They offer a chance at true hyaline cartilage resurfacing.

- No outside laboratory assistance required.

- It can be performed with reusable equipment.

Anatomy and Physiology

There are five different types of cartilage found in the human body: hyaline, fibroelastic, fibrocartilage, elastic, and physeal cartilage. The type of cartilage found lining the articular surfaces of native joints is predominantly hyaline cartilage. The role of hyaline cartilage is to provide a smooth surface that is friction-free and can withstand the joint's repetitive loading and off-loading. The composition of hyaline cartilage is predominantly water, type 2 collagen, and proteoglycans.[11]

By weight, water typically comprises 70 to 80% of the mass of hyaline cartilage. In the presence of osteoarthritis, water content increases, which leads to decreased strength. Articular cartilage consists of five different layers; superficial zone, intermediate zone, deep layer, tidemark, and subchondral bone. When there is damage to articular cartilage that goes deep to the tidemark, this leads to fibrocartilage formation. Fibrocartilage has been formed as a result of the release of pluripotent mesenchymal cells from the bone marrow.

Indications

The indications for osteochondral autograft transplantation varies. Hangody made suggestions for patient selection to maximize the chance for success. This included limiting surgery to patients younger than 45 years with good physical condition and focal lesions. A patient with global arthrosis is less of a candidate than a patient with a symptomatic small focal traumatic lesion. As long as a bony healing response can be expected, a wide range of age is acceptable for surgical indication. Knee joint due to its size and varied pathology is most easily approached with this technique.[12]

A femoral condyle can be approached by an open or an orthoscopic method, but the retropatellar area and trochlear groove need an open approach. The tibia presents a unique difficulty because direct perpendicular access is not possible with either an open or an orthoscopic approach; an indirect retrograde method can be used. Care should be taken to obtain oblique grafts from the donor that match the angle of the recipient tunnel surface angle. Most report full-thickness cartilage lesions between 1 cm and 2.5 cm in diameter are appropriate. Studies have reported favorable outcomes in osteochondral autografts that have been larger, but these numbers are not widely accepted.

Contraindications

Some contraindications to osteochondral autograft include:

- Global arthrosis

- Opposing “kissing” lesions

- Inflammatory arthropathies

- Infection (septic arthritis)

- Biomechanically altered joint line

- Diffuse degenerative changes

The absolute contraindication is global arthrosis. However, focal lesions in two or more areas of the knee may be amenable to this technique. But where secondary changes exist, e.g., osteophytes or joint space narrowing, the efficacy of the procedure is decreased.

Equipment

An operating room will be necessary for this procedure. A standard OR table with a leg holder and an arthroscopic camera/tower will be utilized. Several surgical systems target the harvesting and delivery of osteochondral autografts, any of which can be used.

Personnel

This procedure will require all staff necessary for this procedure to be safely conducted in the operating room. Orthopedic surgeons, surgical assistants, scrub tech, circulating nurse, anesthesia provider, ancillary operating room staff, preoperative care team, the post-operative care team, and medical device representative are necessary personnel.

Preparation

Before the operative intervention, patients are evaluated clinically and undergo diagnostic imaging studies. It is common for full-thickness cartilage lesions to be present in the setting of other ligamentous knee injuries. It is common for patients to report a traumatic event such as pivot-shift injury, fall, patellar dislocation, or direct impact to the injured knee. Radiographic workup consists of standard knee radiographs (AP and Lateral).

Radiographs are not sensitive or specific for detecting cartilage defects, so further imaging such as MRI is routinely used. MRI can detect the depth and size of the chondral defect.[13] The size of the defect becomes important when considering possible treatment modalities. As mentioned earlier, lesions smaller than 1cm in diameter and larger than 2.5 cm in diameter may benefit from different restorative techniques.

Technique or Treatment

There is a stepwise sequence of events to successfully perform an osteochondral autograft that should take place to ensure the best results. There are a few tips and principles that can be useful when pre-operatively planning. It is important to remember that remaining perpendicular to the joint surface that is being restored is a priority. Many of these injuries are located posteriorly on the femoral condyles, so maintaining the ability to hyper-flex the knee is crucial for visualization.

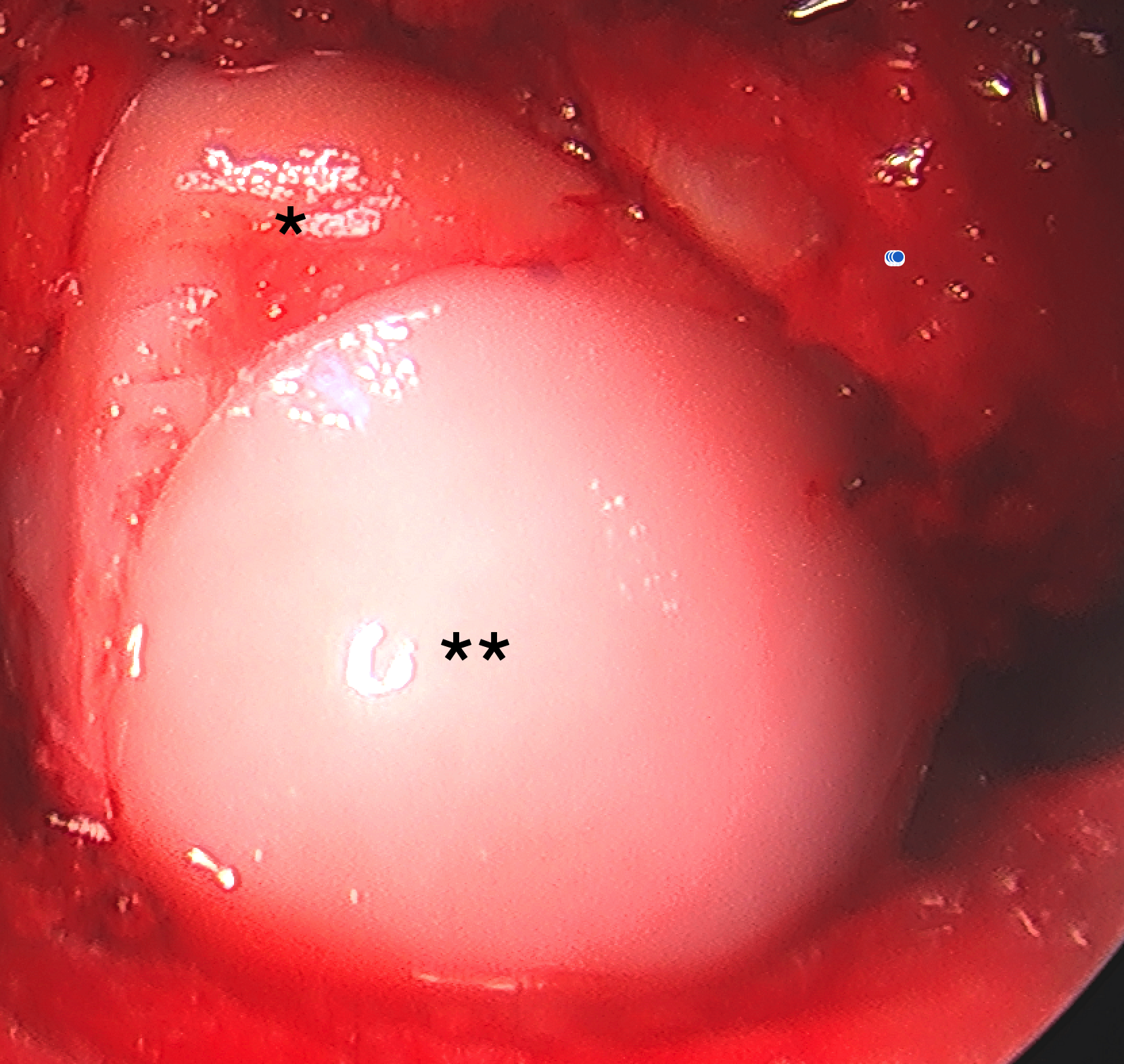

The procedure should begin with a diagnostic arthroscopy, evaluation of all joint surfaces, ligaments, menisci, and medial/lateral gutters. Any loose bodies or chondral fragments should be removed. As mentioned earlier, the visualization of the chondral defects is crucial. Being able to access the defect through portal placement is equally as important. A spinal needle can be used to “trial” correct portal placement to guarantee perpendicular access when placing the new cartilage plug.[14]

When the location of the accessory portal has been established, the defect should be debrided, and the borders of the defect should be defined. If there are loose chondral flaps, those should be removed. Next, the defect is measured, and the decision to utilize one versus multiple bone plugs (mosaicplasty) can be made. The defect is then drilled with a drill bit, which will correspond to the size of the graft that is being placed. The defect needs to be drilled perpendicular to the articular surface. Many of the drill bits have numbers on the sides that measure the depth of the defect. The depth is measured off of the drill bit and where it corresponds to the neighboring cartilage height. Once the defect has been prepared, and the depth of the defect has been established, the focus is then turned to graft harvesting. The donor site is selected based on contact pressure; common locations for graft are the medial and lateral trochlea.

It is common to have a concomitant ACL injury, so many surgeons prefer to harvest from the lateral intercondylar notch, as this area is obliterated while performing a notchplasty in ACL reconstruction. Depending on the system being used, a harvesting tool is impacted into the donor site and driven into the appropriate depth, which corresponds to the depth the recipient site was drilled to. It is essential to insert the harvesting tool perpendicular to the joint surface to prevent graft prominence. The graft is then removed from the donor site and transferred into the delivery system.

The delivery system is used to insert the graft into the defect. Several studies focus on graft insertion protocol and how to ensure that the graft is not damaged upon insertion. Most authors agreed that the insertion force remains under 400N and that the graft is not prominent more than 1 mm or recessed more than 1 mm.[15][16] Leaving the graft prominent can lead to graft failure.

Complications

There are several described complications with osteochondral autografting.

- The donor cartilage can be damaged in the insertion process, leading to degeneration and graft failure.

- The graft can not fit the recipient joint surface topography and can sit proud, leading to excessive forces on the edges of the graft, infection, and graft loosening.

- Donor site morbidity remains a concern for osteochondral transplantation, which includes excessive postoperative bleeding and donor site pain.

Clinical Significance

Osteochondral autografting is a procedure that is performed to restore articular cartilage. When performed correctly, successful outcomes can be achieved in 72% of patients at ten years. This treatment option offers benefits to micro-fracture surgery as it decreases fibrocartilage proliferation, which helps prevent arthritis development.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Osteochondral autograft requires a multidisciplinary team consisting of providers, surgeons, nursing staff, and therapists. Patients with osteochondral defects need to be identified in the clinical setting, appropriate imaging must be obtained, and surgical intervention performed, and he should undergo proper rehabilitation protocol.