Introduction

The kidneys have several essential homeostatic functions. These functions include waste removal (NH3), fluid/electrolyte balance, metabolic blood acid-base balance, as well as producing/modifying hormones for blood pressure, calcium/potassium homeostasis, and red blood cell production. The renal corpuscle (filtration unit, which comprises the glomerulus and the surrounding glomerular or Bowman’s capsule) and tubules (reabsorption and excretion) of the kidney perform the majority of these kidney functions.

The primary function of the kidney, filtering blood, is in part due to its unique blood flow, with high perfusion autoregulation of flow across the glomerular capillaries over a range of pressures. The kidneys receive a high proportion of blood, about 20% of cardiac output, thus enabling the filtration of large volumes of blood. Blood flow autoregulates across the filtration capillaries (glomeruli) due to the unique arrangement of blood vessels. The glomerulus, in contrast to the majority of other capillary beds, sits between two arterioles; receiving blood supply from the upstream afferent arteriole, and blood exiting downstream via the efferent arterioles (E for exit). This arrangement allows for precise control of glomerular flow within the glomerulus, and filtration, rate via autoregulatory changes of the diameters of these resistance arterioles (vasodilation/ vasoconstriction).

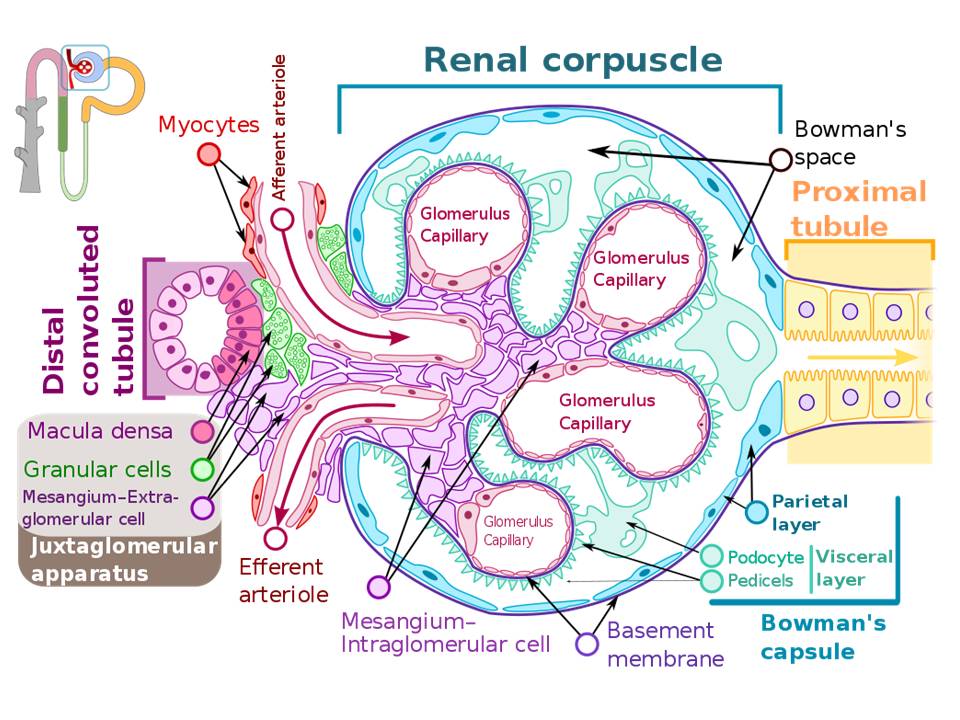

The primary function of the kidney is to filter blood and form urine. The histological structures of the filtering units of the kidney (renal corpuscles) are crucial for this function. The renal corpuscles are located only in the kidney cortex, with about 1 million per kidney with variation due to race. This unique filtration barrier contains three histological structures: the capillary endothelium of the glomeruli, specialized cells called podocytes, and the fused basement membranes of both of these cells (FIG 1). This filtration barrier allows for the filtration of small molecules such as water, ions, creatinine and glucose, and small proteins (less than 90 kDa). This structure must prevent the filtration of large proteins present in the blood, such as albumin and immunoglobulins.

Any aberrance of this filtration barrier leads to pathological conditions. Indeed, about 90% of end-stage kidney disease is due to glomerular diseases.[1] The primary concern is that once damaged; the kidneys have a limited ability to undergo repair. Indeed, most forms of glomerular disease develop gradually with symptoms only appearing after a significant proportion of the kidney functional units are damaged.

Issues of Concern

Glomerular diseases are heterogeneous conditions with a wide variety of etiologies and clinical presentations, but almost universally are due to disruption of the glomerular filtration barrier. These different kidney diseases can broadly separate into two syndromes based on the number of proteins passing into the filtrate or glomerular filtration rate: nephrotic and nephritic.[2] These syndromes are not diseases in themselves, but a set of symptoms, signs, and laboratory findings that suggest an underlying kidney disorder most often involving the glomerulus. While the etiologies and pathologic changes that lead to nephrotic and nephritic syndromes are highly variable, some useful generalizations are possible.

Nephrotic syndrome is mainly due to the destruction of the podocytes (nephrOtic: think O in for podocyte, or O for protein), integral parts of the filtration barrier. Podocyte dysfunction results in significant losses of protein in the urine.

Nephritic syndrome, on the other hand, occurs in kidney diseases attributed to the disruption of the glomerular basement membrane. This pathological change is primarily due to inflammation (nephrItic: think I for inflammation) and results in red blood cells being able to pass through the filtration membrane and giving the urine a cola color (blood in the urine = hematuria).

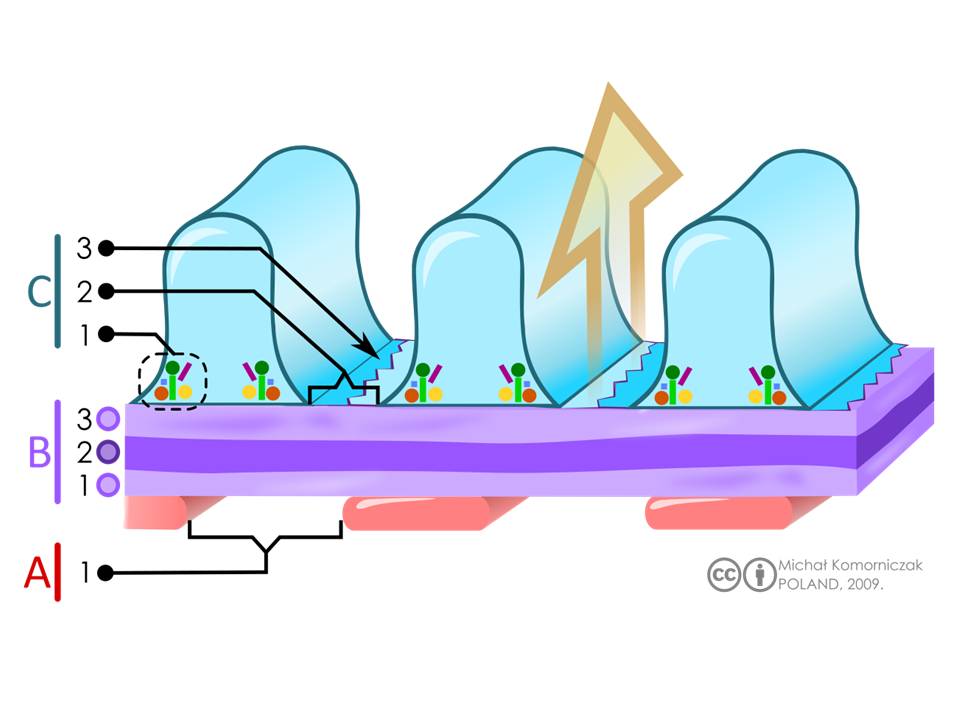

See Figure 1: Structure of glomerulus

Structure

The renal corpuscle consists of several histological structures (FIG 1):

Glomerulus capillaries form a central tuft of looped capillaries located in the center of the renal corpuscle. These capillaries deliver blood and create a large surface area for renal filtration. These capillaries are optimized for filtration. The blood flow is regulated over broad ranges of pressures, thus keeping the glomerular filtration rate relatively constant. This regulation occurs via the capillaries' unique location between two resistance arterioles (afferent and efferent, think E for exit).[3] Second, they present a large porous surface area for filtration. The glomerular capillary endothelium contains small transcellular pores or fenestrations (windows) of approximately 60 nm in diameter, which covers about 20 to 50% of the endothelial surface.[4][5][6] While these pores are large, the thought is that the negatively charged glycocalyx covering the luminal endothelial cell surface prevents the filtration of molecules over 100 nm.[4][6] Third and last, these capillaries are not embedded within a supporting intracellular matrix but are relatively "free" within the Bowman's capsule. Thus it is fitting that the term glomerulus originated from the Greek word "filter."

Intraglomerular mesangial cells physically support the glomerular capillaries, occupy the intercellular spaces underneath the basement membrane. They are generally on the opposite side of the glomerulus from the podocytes.[3] (FIG 1) Glomerular capillaries require a unique support structure because they are not surrounded by interstitial tissue. The kidneys have very few stromal cells.[3] These mesangial cells are relatively small, irregular in shape, have scant cytoplasm, and have heterochromatic and indented nuclei.[7] Both mesangial cells and their secreted extracellular matrix, are collectively termed mesangium. Expansion of mesangial cells in some renal diseases results in a reduction of the filtration area and occlusion of glomerular capillaries.[4]

Mesangial cells have additional functions, contractile, and phagocytic functions.[7] There is some evidence that mesangial cells can be induced to secrete erythropoietin (EPO), but it is now a more accepted position that EPO production occurs in peritubular cells.[8][9][10][11][12][13] The contractility alters glomerular capillary diameter in response to blood pressure changes, resulting in a fine-tuning of glomerular filtration rates.[3] The phagocytic function removes protein aggregates, such as immune complexes, that lodge within the glomerular filter. Since mesangial cells secrete erythropoietin (EPO) in response to hypoxia, damage can also affect red blood cell formation and hematocrit.

Bowman's capsule consists of the visceral and parietal layers (FIG 1). The inner visceral layer completely encircles the glomerular capillaries. It is comprised of specialized stellate epithelial cells termed podocytes. In contrast, the outer or parietal layer of Bowman's capsule is a single layer of simple squamous epithelium. It is into the space between these two layers into which urine is filtered.

Podocytes serve both as support of glomerular capillaries and are part of the glomerular filtration barrier. They are large cells with euchromatic nuclei and form the visceral layer of the Bowman's capsule with exposure to the urinary space (FIG 1). The interdigitating secondary processes of the podocytes (pedicels, or foot processes) cover and encircle much of the surface of the glomerular capillaries. These foot processes contain actin and are thought to have some contractile activity top oppose distension of the glomerular capillaries.[14] The spaces or gaps between these interdigitating pedicels form slit pores approximately 30 to 40 nm wide.[14][15] These slits are covered by a thin membrane or slit diaphragms.[4] Podocytes have limited repair capacity but can regenerate foot processes (pedicels).[3] Pedicel loss is referred to as effacement and also simplification, retraction, or fusion.[3][14]

The slit diaphragms are specialized adherens junctions with nephron and other proteins forming a zipper-like structure with small pores about the size of an albumin molecule.[14][16][4][15] The protein barrier is due to the sieving of the filtrate by these small pores.[16][4] In addition to the pores, a negatively charged glycocalyx covers the podocytes and slit diaphragm; the negative charges also have an important barrier function and repel negatively charged proteins such as albumin [3][4]. It bears mentioning that the slight diaphragm is only visible by electron microscopy. Whether the slit diaphragm is the major factor in permeability selectivity is a topic of debate.[14]

The glomerular basement membrane is the third component of the filtration barrier, along with the capillary endothelium and podocytes (FIG 1, and 2). It is a fused basement membrane of the endothelial cells and podocytes, and also offers some support to the glomerular capillaries.[5][17] Thus it is thicker (240 to 270 nm) than other capillary basement membranes (40 to 80 nm) [4]. It is a gel-like material containing an organized fibrous mesh-like network forming heterogeneous pores of 10 nm.[3][18] The primary component is type IV collagen but contains other proteins such as laminin, and heparan sulfate, glycoproteins, and the proteoglycans agrin and perlecan.[3][4][5] The mesh-like structure and negative charges form a molecular sieve or barrier, preventing high molecular weight proteins such as albumin and globulin (antibodies)s from leaving the circulation [6]. The precise role of the glomerular basement membrane in selective permeability has recently come under debate, but it undisputedly restricts fluid flux.[4][18]

The juxtaglomerular apparatus is an important group of structures located at the entry of the capillaries in the glomerulus (FIG 1). Two of these are specialized sensory structures that have feedback mechanisms to regulate glomerular blood flow and filtration rate.

- Macula densa (thicker spot) is a thickened region of the distal convoluted tubule. It is characterized by apical nuclei and tightly packed columnar cells. It responds to the salt concentration in the tubule filtrate and is a tubuloglomerular feedback system that regulates the glomerular filtration rate. It is important to note that the macula densa regulates the glomerulus that connects to the distal tubule, which detects the salt concentration.

- Juxtaglomerular cells (also granular cells) are specialized smooth muscles in the walls of the afferent arteriole. These cells synthesize and secrete renin in response to decreased arteriolar blood pressure and activate the renin-angiotensin system to regulate blood pressure.

- Lacis cells are extraglomerular mesangial cells and are in the stalk of the glomerular tuft of capillaries.[3] They have similar functions as the intraglomerular mesangial cells.

Function

Structure of the filtration barrier. A= Endothelial cells (pink) of fenestrated glomerular capillaries, with the label 1 depicting the fenestra or pore. B = glomerular basement membrane (purple). There are three layers that visible with electron microscopy. They are labelled as 1 = lamina rara interna, 2 = lamina densa, 3 lamina rara externa C: interdigitating podocytes endfeet with slits (blue) with labelling for 1= intracellular enzymes, 2= slits, and 3= slit diaphragms. The large arrow (orange) indicates the direction of the flow of the filtrate through the filtration barrier.

Fig 2 and Legend

This glomerular filtration barrier is comprised of three structures: the glomerular capillary endothelium, podocytes, and the fused basement membranes of both of these cells (FIG 2). This filtration barrier is responsible for the selective permeability by size and charge in renal filtration of substances by the kidney. Small molecules (less than 10kDa) that are not bound to plasma carrier proteins, such as water and salts, are freely filterable. With increased molecular weights, filtration decreases until proteins that are larger than ~ 90kDa, after which no filtration occurs.[4][14]

We should note that while albumin has a molecular weight of approximately 66 kDa and has a negative charge, there is only a loss of 0.1% albumin in plasma.[4][14] This is because, in addition to a barrier based on the sieving through pores, negative charges are also a part of the filtration barrier. A net negative charge is present on the endothelial lumen, podocytes, and glomerular basement membrane, which electrostatically repels negatively charged molecules such as albumin.

The actual functional mechanism underlying glomerular filtration is a balance between hydrostatic and colloid osmotic pressures, or Starling forces, across the filtration barrier. The glomerular capillary pressures force water and salts out of the blood into the Bowman's urinary space. The colloid osmotic pressures are primarily due to albumin, which keeps water in the capillaries. In effect, albumin binding of sodium acts as a sponge, keeping and pulling extra fluid from the body into the blood. Generally, the hydrostatic pressures are greater than the oncotic pressures, resulting in glomerular capillary filtration.

Another important structure in the glomerulus is the juxtaglomerular apparatus, components of which respond to increased glomerular filtration rate (GFR), and decreased blood pressure. The macula densa detects the increased glomerular filtration rate (GFR) as an increase in salt concentration within the distal tubule filtrate. The macula densa responds by releasing substances that cause vasoconstriction, the afferent arteriole, decreasing blood flow and pressure, and thus normalizing GFR. Decreased glomerular blood pressure is regulated by the granular (or juxtaglomerular cells), so named due to the intracellular granules that store renin before release. These cells release renin the renin, stored in intracellular granules. Renin activates the renin-angiotensin system to return blood pressure to normal and increase blood volume (via aldosterone mediate water reabsorption in the tubules).

Tissue Preparation

Evaluation of glomerular histology has clinical relevance principally in the setting of renal biopsies for kidney diseases. Indications for renal biopsy are not well-established and somewhat controversial. The most common medical indication worldwide for a renal biopsy is nephrotic syndrome. In patients with chronic kidney disease and/or end-stage renal disease, renal biopsies altered the clinical approach in 31 to 57% of cases.[19] Additionally, biopsies also play a critical role in monitoring for rejection in the case of renal transplantation and the evaluation of tumors of the kidney, although the glomerulus is not as frequently the focus of those assessments

A full description of the pathologic assessment of the medical renal biopsy is beyond the scope of this review; however, a summary of pathologic findings of commonly encountered diseases appears in Tables 1-3. For the medical student and non-pathologist physician, it is important to understand that the value of the information obtained from the biopsy has an intricate link to the quality of the biopsy technique and processing procedures employed. Therefore, the following will include a brief review of the highlights of renal biopsy processing to maximize the value of histologic evaluation.

Native kidney biopsies (as opposed to allografts) are most commonly performed percutaneously with the patient in the prone position using a 14 to 18 gauge needle. The lower pole of the kidney is typically biopsied when no specific target is identified, and a general kidney assessment is a goal. The procedure is performed using local anesthetic and lancing of the skin before inserting the needle.[20] While all procedures carry some amount of risk, modern renal biopsy practice is relatively safe. Hematuria identified by any means will be present in slightly more than a third of patients, and 0.5% of patients will present with gross hematuria. Severe complications necessitating transfusion occur in fewer than 0.1% of cases.[21]

Comprehensive pathologic evaluation of the biopsy requires assessment with three modalities: light microscopy, immunofluorescence/immunohistochemistry, and transmission electron microscopy. The choice of immunofluorescence and immunohistochemistry is dependent upon the facilities available and the pathologist’s experience. Immunofluorescence is more common in the United States, whereas immunohistochemistry is performed more frequently in Europe. Following the biopsy, the sample requires separation into three parts for the microscopic evaluation. An experienced technician or pathologist should be present at this stage. Glomeruli are observable using a dissecting microscope. The division of the biopsy core will ensure the appropriate placing of glomerular tissue in each of the three media.

Microscopy, Light

Light Microscopy

Transport of the portion of the biopsy bound for light microscopy can be in standard buffered formalin solution at room temperature. The tissue should be wrapped in lens paper to prevent loss during processing. Using net bags or sponges introduces artifacts that will interfere with interpretation and should be avoided if possible. After fixation, the tissue will be embedded in paraffin. Sectioning should be done with 2 to 4 micrometers serial sections with multiple sections per slide. Each institution tends to have its standardized practice for how many slides are initially created and which stains are initially performed. Standard stains include hematoxylin and eosin (H&E), periodic acid-Schiff, a silver stain, and trichrome stains.[20]

Immunofluorescent Microscopy

Immunofluorescent protocols generally call for tissue to be frozen rather than fixed. Fixation of tissue does not completely eliminate the possibility of performing immunofluorescence; however, it is not as ideal. Cross-linking fixatives, such as formalin and glutaraldehyde, are excellent at preserving morphologic integrity but may cross-link target antigens and introduce too much background autofluorescence. If the biopsy is being performed near the lab doing the procedure, then the tissue can be transported in regular saline. If the sample needs to travel further, then a medium such as Michel medium is preferred. Sectioning can occur on a cryostat with 2 to 4 μM sections. Again, the standard workup is institution-dependent; however, routine examination typically includes IgG, IgM, IgA, complement proteins (C3, C1q, C4), fibrin, and kappa/gamma light chains along with appropriate controls.[20]

Microscopy, Electron

Ice-cold glutaraldehyde (1 to 3%) is the most commonly used fixative for electron microscopy. Other fixatives, such as paraformaldehyde or formalin, can be used but are not as ideal. Standard electron microscopy (EM) processes are in order as per institution protocol. Usually, a relatively thick (1 micrometer) section undergoes evaluation to select a glomerulus in the given tissue, which is then sectioned into ultra-thin slices for placement on a copper grid.[20] Ultrastructure is examined at multiple levels to assess all components of the glomerulus previously discussed.

Pathophysiology

There are several signs of glomerular dysfunction that can be used in the diagnosis and are also used to separate diseases into nephrotic or nephritic syndromes.

- Protein in the urine (proteinuria): This is a hallmark measure of renal disease, and the primary measure used to differentiate between nephrotic and nephritic syndromes. Protein in the urine can be due to glomerular disease-causing proteins to leak into the urine, or a defect in protein reabsorption in the kidney tubules. Proteinuria may cause foamy urine. Generally, very high protein concentration in the urine or "nephrotic range" > 200 mg/l is associated with podocyte disruption, which results in non-selective protein loss.[4] Losses of protein into the urine is typically associated with reduced proteins or albumin in the blood (proteinemia or hypoalbuminemia).

- Blood in the urine (hematuria): The presence of hemoglobin from leaked red blood cells gives the urine a pink or light brown (cola-colored). This presentation is a typical symptom of nephritic syndrome, along with lower proteinuria, and is proteinuria is associated with nephritic attributable to a defect in the glomerular basement membrane.

- Edema: Protein losses from the blood results in a reduction of colloid oncotic pressure and increased filtration from the capillaries resulting in the excess, non-resorbed fluid accumulation within the intercellular spaces to cause swelling. This swelling due to edema is usually more noticeable in the hands, ankles, or periorbitally.

- Uremia: reduced glomerular filtration rate: Disruption of the barrier can also result in reduced filtration and thus the accumulation of waste products such as. Creatinine and urea nitrogen in the blood.

Acidosis: This is beyond a discussion of the glomerulus, but still bears mentioning. Kidney tubules are involved in the metabolic acid-base homeostatic regulation of blood pH.

Tables 1-3 and Legends

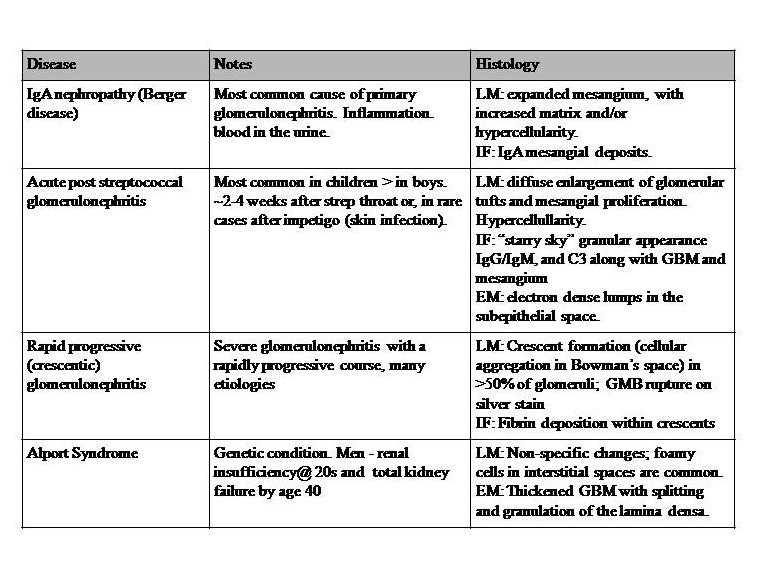

Table 1: Diseases with Nephritic syndromes. This syndrome is a set of symptoms generally attributed to inflammatory processes, and not a disease in itself. It involves disruption of the glomerular basement membrane, and common features include hypertension (salt retention), increased blood urea nitrogen (BUN), creatine, oliguria, hematuria, and red blood cell casts. Proteinuria of less than approximately 3.5 g/day. References for diseases in table 1: Le et al. 2019 First Aid for the USMLE McGraw Hill pp 583-5,[4][22][23]. Key: GBM = glomerular basement membrane, LM= light microscopy, IF = immunofluorescence, EM = electron microscopy, IgG = immunoglobulin G, C3 = complement C3.

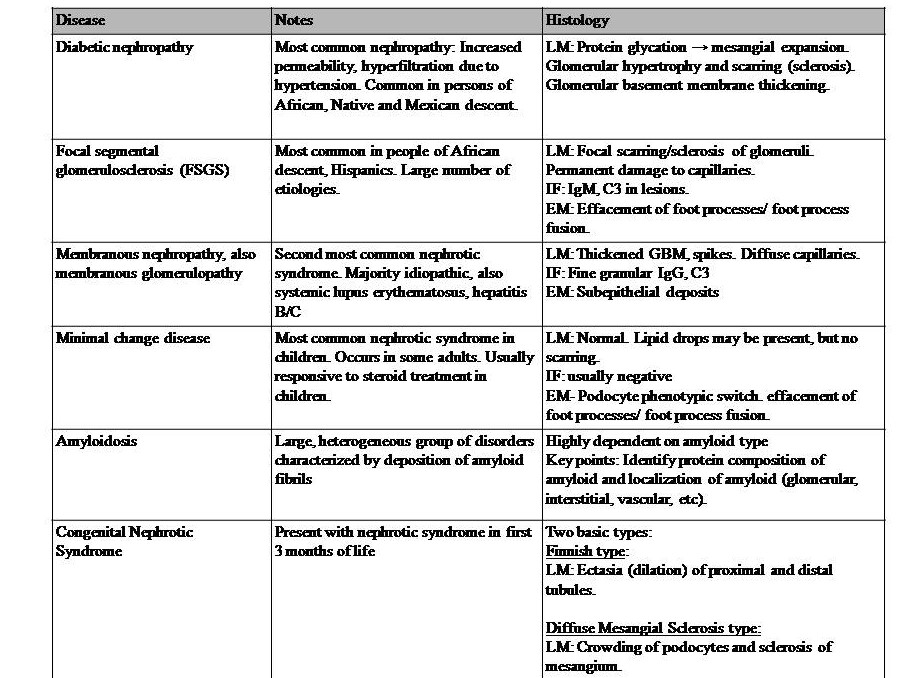

Table 2: Diseases with Nephrotic syndromes. This syndrome is also a set of symptoms and not a disease in itself. It can occur with many diseases; thus, the basis of prevention is controlling the underlying causal diseases. This syndrome is generally due to podocyte disruption, resulting in impairment of the charge barrier. This syndrome is characterized by massive proteinuria > 3.5g/day with hypoalbuminemia, hyperlipidemia, and edema.[24] Also, there is an increased risk of venous thromboembolism in adults, especially of the renal vein. Edema is due to the loss of proteins. Dyslipidemia is originally thought to be due to increased albumin metabolism in the liver, but now this might be instead due to altered lipoprotein synthesis of cholesterol transport from peripheral tissues to the liver.[25][26] Thromboembolism is due to the loss of the clotting protein antithrombin III.[26] References for diseases in table 2: Le et al. 2019 First Aid for the USMLE McGraw Hill pp 583-585,[24][1][27][28][29][30]. Key: GBM = glomerular basement membrane, LM= light microscopy, IF = immunofluorescence, EM = electron microscopy, IgG = immunoglobulin G, C3 = complement C3.

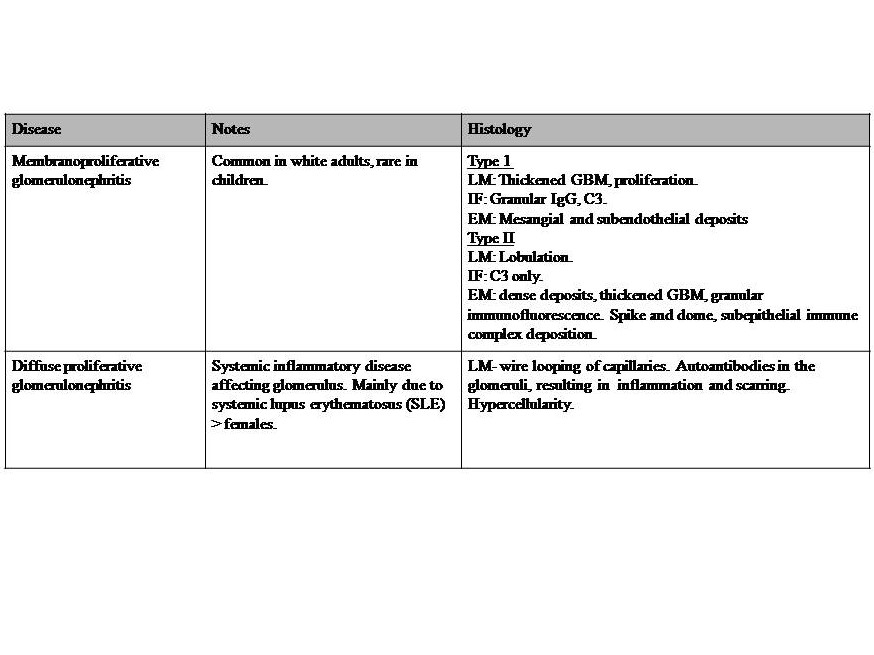

Table 3: Diseases with both Nephritic-nephrotic syndromes. Severe nephritic syndrome with profound glomerular basement membrane damage, resulting in a change of the charge barrier. Nephrotic range proteinuria (>3.5 g/day), and features of nephrotic syndrome. Reference for diseases in table 3: Le et al. 2019 First Aid for the USMLE McGraw Hill pp 583-5,[24][27]. Key: GBM = glomerular basement membrane, LM= light microscopy, IF = immunofluorescence, EM = electron microscopy, IgG = immunoglobulin G, C3 = complement C3.

Clinical Significance

Glomerular damage leads to several pathologies, described below. The pathologies are readily diagnosable using blood and urine analysis. With kidney disease, one should additionally keep homeostatic regulation of red blood cell production (hematocrit), calcium and vitamin D homeostasis, blood pressure/volume, and acid-base balance in mind.