Continuing Education Activity

Anterior hip dislocations are usually caused by forceful abduction with external rotation of the thigh and most commonly following a motor vehicle accident or fall. Enormous force is required to dislocate a hip as it is quite stable due to its bony construction and the associated muscular and ligamentous attachments. This activity describes the classification, evaluation, and management of anterior hip dislocations. It also affirms the role of an interprofessional team consisting of the nurse, emergency physician, and an orthopedic practitioner in reducing the dislocation swiftly without surgery, and hence decreasing morbidity in patients with anterior hip dislocation.

Objectives:

- Describe the clinical presentation of anterior hip dislocation.

- Describe the detailed evaluation of anterior hip dislocation.

- Outline the management including reduction of dislocation and interventional options for patients with anterior hip dislocation.

- Review the role of improving coordination amongst the interprofessional team to streamline diagnosis, joint reduction, and/or surgery for patients with anterior hip dislocation.

Introduction

Hip dislocations after trauma are frequently encountered in the emergency setting. A significant force is generally required to dislocate a hip as this ball and socket joint is quite stable due to its bony structure and the associated muscular and ligamentous attachments. Due to the required force, hip dislocations often are associated with other significant injuries; for example, fractures are found in over 50% of these patients. The majority of all hip dislocations are due to motor vehicle accidents. Posterior hip dislocations are the most common type, with anterior occurring only about 10% of the time. These injuries are true orthopedic emergencies and should be reduced expediently. The majority will resolve with a closed reduction in the emergency department.[1][2][3]

Anatomy

The hip joint is a synovial ball-and-socket structure with stability related to both its bony and ligamentous arrangement. The acetabulum covers approximately 40% of the femoral head during all maneuvers, and the labrum serves to deepen this joint and adds additional stability. Furthermore, the hip joint capsule is composed of dense fibers that preclude extreme hip extension. The main blood supply to the femoral head arises from the medial and lateral femoral circumflex arteries, which are branches of the profunda femoral artery. Branches off of this supply enter the bone just inferior to the femoral head after ascending along the femoral neck. This arrangement allows for a plentiful but tenuous blood supply to the femoral neck, especially when considering a traumatic hip injury to the femoral head. The sciatic nerve exits the pelvis at the greater sciatic notch and lays just infero-posterior to the hip joint. The femoral nerve lies just anterior to the hip joint.

Etiology

Anterior hip dislocations are usually the result of a significant force, such as trauma, or from a poorly positioned total hip arthroplasty. In a traumatic setting, the hip is forced into abduction with external rotation of the thigh and often related to a motor vehicle accident or fall. There are three types of anterior hip dislocations: obturator, an inferior dislocation due to simultaneous abduction; hip flexion; and external rotation. Iliac and pubic dislocations are superior dislocations due to simultaneous abduction, hip extension, and external rotation.[4][5] Bourne et al. state that total hip arthroplasty has an overall dislocation rate of 0.3-10%, and increases to 28% in the revision setting. [6] Recent literature has shown that anterior total hip arthroplasty has near equivalent rates as the posterior approach. Increasing education in the anterior approach may lead to an overall increase in hips performed anteriorly and a subsequent increase in anterior hip dislocation and complications associated with the anterior approach.

Epidemiology

Hip dislocations are most common in young adult males and are most often the result of motor vehicle accidents. A recent study suggested the average age of these patients to be 34.4, with over 90% male. Associated injuries were found in 74.4% of patients with the most common involving fractures of the hip. Over 90% were treated with a closed reduction, and approximately 70% were reduced within 12 hours. One study suggested an increase in long-term complications from 22% to 52% with a delay of over greater 12 hours. Anterior dislocations of the hip in children are rare.

Brennan et al. found that dislocation following total hip arthroplasty (THA) occurs in 3.8% of patients when followed for ten years. [7] The majority of anterior hip dislocations occur in the first month and is the most common reason for revision arthroplasty in the first two months. Many factors may predispose a patient to dislocate and include;[7]

- History of repeat hip surgery

- Sex = Female

- Age = older (70-80 years old)

- Neuromuscular Disease

- Social Factors (alcohol, drug, activity)

- Surgical Factors (offset, abduction, anteversion, head/neck ratio)

Pathophysiology

Injury Description

Epstein classification of anterior hip dislocations

Type 1: Superior dislocations

- 1A: No associated fracture

- 1B: Associated fracture or impaction of the femoral head

- 1C: Associated fracture of the acetabulum

Type 2: Inferior dislocations

- 2A: No associated fracture

- 2B: Associated fracture or impaction of the femoral head

- 2C: Associated fracture of the acetabulum

Comprehensive classification of hip dislocations

This system includes both anterior and posterior dislocations and incorporated pre- and –post findings.

- Type I: No significant associated fracture, no clinical instability after reduction

- Type II: Irreducible dislocation (after attempt under general anesthesia) without significant femoral head or acetabular fracture

- Type III: Unstable hip after reduction or with incarcerated fragments of cartilage, labrum, or bone

- Type IV: Associated acetabular fracture requiring reconstruction to restore hip stability or joint congruity

- Type V: Associated femoral head or neck injury

History and Physical

Patients with hip dislocations generally arrive in severe pain in the hip area; however, reports of pain in the knee, lower back, thigh, or even lower abdomen or pelvis are not uncommon. Superior anterior dislocations classically present with the hip extended and externally rotated while inferior anterior dislocations generally present with the hip abducted and externally rotated. It is important to note that additional bony leg injuries may alter this classic presentation.

A thorough neurovascular exam is also required. Injuries to the femoral artery, vein, or nerve may rarely occur with anterior dislocations and should also be sought out. Femoral nerve motor function may be difficult to assess fully due to pain and the nature of this injury; however, sensory deficits over the anteromedial aspect of the thigh and medial side of the leg and foot should raise suspicion. Sciatic nerve injuries occur more often with posterior dislocations; however, they should be ruled out in any hip dislocation or fracture.

Due to the required mechanism of injury related to these dislocations, a full trauma evaluation for other associated injuries should be considered.

Evaluation

Imaging

X-rays

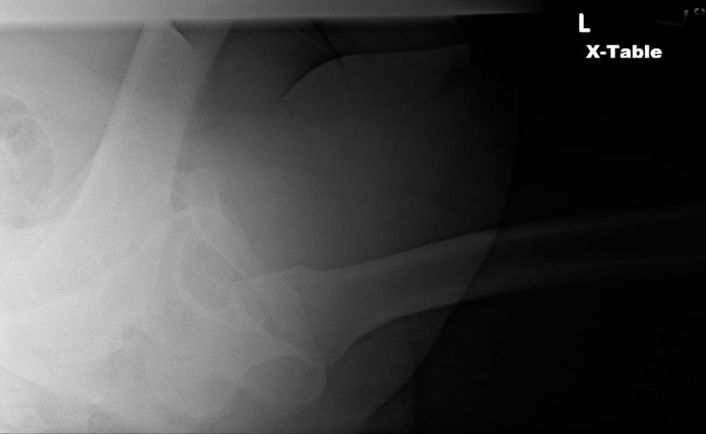

Hip dislocations usually are obvious on standard AP (anteroposterior) images of the pelvis. However, complete imaging usually includes a cross-table lateral of the affected joint.

On a normal AP pelvis, the femoral heads should appear similar in size with symmetric joint spaces. The joint with an anterior dislocation will project a larger-appearing femoral head. A femoral neck fracture should be ruled out by this image prior to attempting reduction.

Judet views (45 degree internal and external oblique views) may be of some help in evaluating for bone fragments and occult acetabular and femoral head and neck fractures.

Computed tomography

CT (Computed tomography) is recommended after a successful, closed hip reduction to evaluate for occult fractures. It may also further elucidate the cause of postreduction joint space widening and find intra-articular bone fragments or soft tissue injury that may prevent appropriate joint articulation. Moreta et al. found loose bodies in 20% of the hips that underwent post-reduction CT.[8]

CT also may be helpful in preoperative planning when a closed reduction is unable to be obtained and surgical, open reduction is required. Similar to postreduction joint space widening, findings on CT after unsuccessful reduction attempts may elucidate bone fragments or soft tissue abnormalities that both explain the inability to perform a closed reduction and assist in surgical planning.

MRI

MRI may be indicated to evaluate for soft tissue injuries and cartilaginous bodies that continue to cause issues after the acute period. Osteonecrosis also may be seen in the subacute period (4 to 8 weeks), and some have suggested that MRI is superior to CT for children with hip injuries as CT may miss unossified labrum and acetabular fractures.

Other Testing

Laboratory studies should be tailored to the individual patient; however, if significant blood loss is suspected due to femoral vessel injury, serial hemoglobin/hematocrit and a type and screen may be requested.

Treatment / Management

Prompt reduction of any hip dislocation is imperative. Attempts should be made to impart a reduction within six hours. However, the traditional rule of a concentric reduction within six hours has been challenged by many. Letournel and Judet found no significant difference in osteonecrosis when patients were reduced up to 72 hours. [9] These patients are usually in considerable discomfort. Initial analgesia should be given with thought to the possibility of other associated injuries.[1][10] Irreducible hip dislocations are often secondary to inadequate posterior or anterior wall support or entrapped structures. The labrum, ligamentum teres, capsule, iliopsoas, pulvinar, and synovium, were trapped in the joint and prevented close reduction.

Indications for Open Reduction

- A nonconcentric reduction (indicating a retained loose body or significant soft tissue injury preventing proper reduction)

- An associated acetabular or femoral head fracture that will require an open repair

- Femoral neck fracture

- A dislocation that is not reducible by closed reduction techniques

Patients who do not warrant an open reduction should have an urgent closed reduction in the emergency department under procedural sedation.

Anterior Hip Dislocation Reduction Techniques

Allis Maneuver

The Allis Maneuver is the most common method performed and differs slightly from the Allis maneuver used for posterior hip reductions. The patient lies supine with the practitioner standing over them. An assistant stabilizes the pelvis by applying pressure over the bilateral anterior superior iliac spines. The practitioner holds the affected leg just below the knee and, while slightly flexing the hip, applies constant traction to the hip joint along the long axis. The hip may be internally rotated and adducted. A gentle lateral force to the thigh may be of some assistance. The reduction is performed until an audible click is heard, suggesting a successful reduction.

"Captain Morgan" Technique

The "Captain Morgan" Technique is a more novel approach named after the character on the spirit bottle. The patient lies supine with both the knee and hip flexed. The practitioner positioned their foot on the patient's stretcher with their knee bent (hence the "Captain Morgan" moniker) and positioned behind the patient's knee. The practitioner places a hand under the patient's knee and the other on their ankle. With the first hand, the practitioner lifts the patient's femur while plantar flexing their ankle to raise the patient's femur. The practitioner then applies gentle downward pressure over the patient's ankle. This "leverages" the hip back into place. Stabilization of the pelvis by a strap or an assistant may be helpful.

Reverse Bigelow Maneuver

The patient is positioned supine with the hip partially flexed and abducted. A firm jerk is then applied to the thigh. Another variation has the practitioner apply traction longitudinally with hip adducted and apply abrupt internal rotation and extension of the hip

Stimson Maneuver

This technique also is less frequently used due to difficult patient positioning; however, it is often suggested to be a less traumatic process. The patient is placed in the prone position with the affected leg allowed to hang from the side of the bed; the knee and hip are flexed while an assistant stabilizes the patient's lower back. Traction is applied downward by the practitioner who is holding the leg just below the knee. This allows gravity to assist with the traction. Internal and external rotation are applied until a successful reduction is felt.

Post Reduction Care

Patients should be positioned with legs immobilized in slight abduction with a pillow or device between the knees. Ice packs should be applied, and analgesia is required. The patient should have post-reduction x-rays done and admission for continued orthopedic care. It is critical to evaluate the stability of the hip when a patient suffers an anterior hip dislocation after total hip arthroplasty. The patient should be tested under anesthesia, and the degree of flexion, adduction, and internal rotation should be recorded. A hip abduction brace may benefit a patient who continues to disregard precautions.

Open Reduction

Multiple surgical approaches for reducing an anterior hip joint are possible; however, all require joint irrigation to remove any bony or soft tissue structures that would prevent a concentric reduction. Postoperatively reduced hips should be held in traction for 6 to 8 weeks, until definitive fixation, or until the pain has entirely resolved.

Differential Diagnosis

- Femoral neck fracture

- Hip subluxation

- Bony contusion

- Ipsilateral knee, spine, pelvis injuries

- Slipped capital femoral epiphysis

- Intra-abdominal or pelvic pathology.

Prognosis

- Femoral head trauma: Anterior hip dislocations commonly are associated with femoral head trauma and therefore have a higher incidence of long-term decreased functional outcomes and post-traumatic arthritis. Moreta et al. found that 13.3% of patients that suffered a complex dislocation had radiographic signs of osteoarthritis.[8] Approximately 50% of all anterior dislocations have femoral head indentation fractures; however, patients without these associated fractures often have an excellent, long-term outcome.

- Osteonecrosis: This complication ranges from 5% to 40% of all hip dislocations but is related to the time before the joint's reduction, with over 6 hours increasing the risk. Up to 20% of all traumatic hip dislocations will suffer osteonecrosis of the hip. [11]

- Thromboembolism: Patients are at an increased risk of thromboembolism due to both immobility post-injury and due to vascular intima injury related to traction. Rezaie et al. found a 0.5% risk of venous thromboembolism after surgical hip dislocation. Prophylaxis should be the standard for this group. [12]

- Recurrent dislocation: This occurs in approximately 2% of patients. Itokawa et al. found that 40% of patients who dislocated after total hip arthroplasty, suffered repeat hip dislocations. [13]

- Neurovascular injury: Although the injury to the femoral nerve or vasculature has been reported, it remains relatively rare. Cornwall et al. found 10% of adults and 5% of children will suffer neuropraxia following hip dislocation. Fortunately, 60-70% of patients had partial resolution of symptoms. [14]

Postoperative and Rehabilitation Care

Postreduction Care

Patients should be positioned with legs immobilized in slight abduction with a pillow or device between the knees. An abduction brace may be prescribed and is at the provider's discretion. A knee immobilizer offers additional support in the posterior hip dislocation but has no role in the anterior hip dislocation. The patient should have post-reduction x-rays and admission for continued orthopedic care.

Consultations

Orthopedic surgery consultation should be requested after a successful emergency reduction or if there is an indication for emergent operative reduction (most commonly, the inability to reduce the dislocation). Trauma surgery also may be consulted if there are other non-bony injuries.

Pearls and Other Issues

Anterior hip dislocations must be reduced expediently. Delays of more than 6 hours correlate with increased long-term morbidity, most notably osteonecrosis of the femoral head. Anterior hip dislocations without indications for surgical repair are generally reducible in the emergency department under procedural sedation using one of the multiple techniques. Postreduction orthopedic consult and admission are appropriate.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Hip dislocations after trauma are frequently encountered in the emergency setting. Significant force is generally required to dislocate a hip as this ball and socket joint is quite stable due to its bony structure and the associated muscular and ligamentous attachments. Due to the required force, hip dislocations often are associated with other significant injuries; for example, fractures are found in over 50% of these patients. The nurse practitioner and emergency department physician must consult immediately with an orthopedic surgeon. These injuries are true orthopedic emergencies and should be reduced expediently. The majority will resolve with a closed reduction in the emergency department. An interprofessional team consisting of the nurse, emergency physician, and an orthopedic surgeon can most often reduce the dislocation without operative intervention.