Continuing Education Activity

Costochondritis is a benign cause of chest wall pain from costal cartilage inflammation at the rib-to-sternum articulation. Patients present with upper chest wall pain provoked by movement without associated symptoms, such as shortness of breath, coughing, fever, or rash. Costochondritis can mimic myocardial infarction, pneumonia, Herpes zoster, and systemic disorders associated with chest wall or back pain. A comprehensive history and physical exam help exclude chest pain etiologies before making a costochondritis diagnosis. A chest x-ray and electrocardiogram should be considered for all adult patients with chest pain. Costochondritis can be managed with topical analgesics or oral anti-inflammatory medications.

This activity for healthcare professionals is designed to enhance learners' proficiency in evaluating and managing costochondritis. Learners improve their skills in differentiating the condition from serious chest pain causes and providing the appropriate management plan, including diagnostic tests and treatments. Participants become equipped to collaborate effectively within an interprofessional team caring for patients with costochondritis.

Objectives:

Differentiate costochondritis from other sources of chest pain based on clinical findings.

Create a clinically appropriate diagnostic strategy for a patient with possible costochondritis.

Develop an individualized management plan for a patient diagnosed with costochondritis.

Apply effective strategies to enhance care coordination among interprofessional team members, facilitating positive outcomes for patients with costochondritis.

Introduction

Costochondritis Overview

Costochondritis, also known as costosternal or anterior chest wall syndrome, is related to inflammation of the cartilages connecting the ribs to the sternum. This benign condition presents with localized chest pain exacerbated by movement or palpation, often mimicking more severe conditions like cardiac issues. Diagnosis relies on clinical assessment, excluding serious causes, with treatment involving conservative measures such as nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and physical therapy. Interprofessional collaboration ensures comprehensive patient care and improved outcomes despite its benign nature.

Chest Wall Anatomy

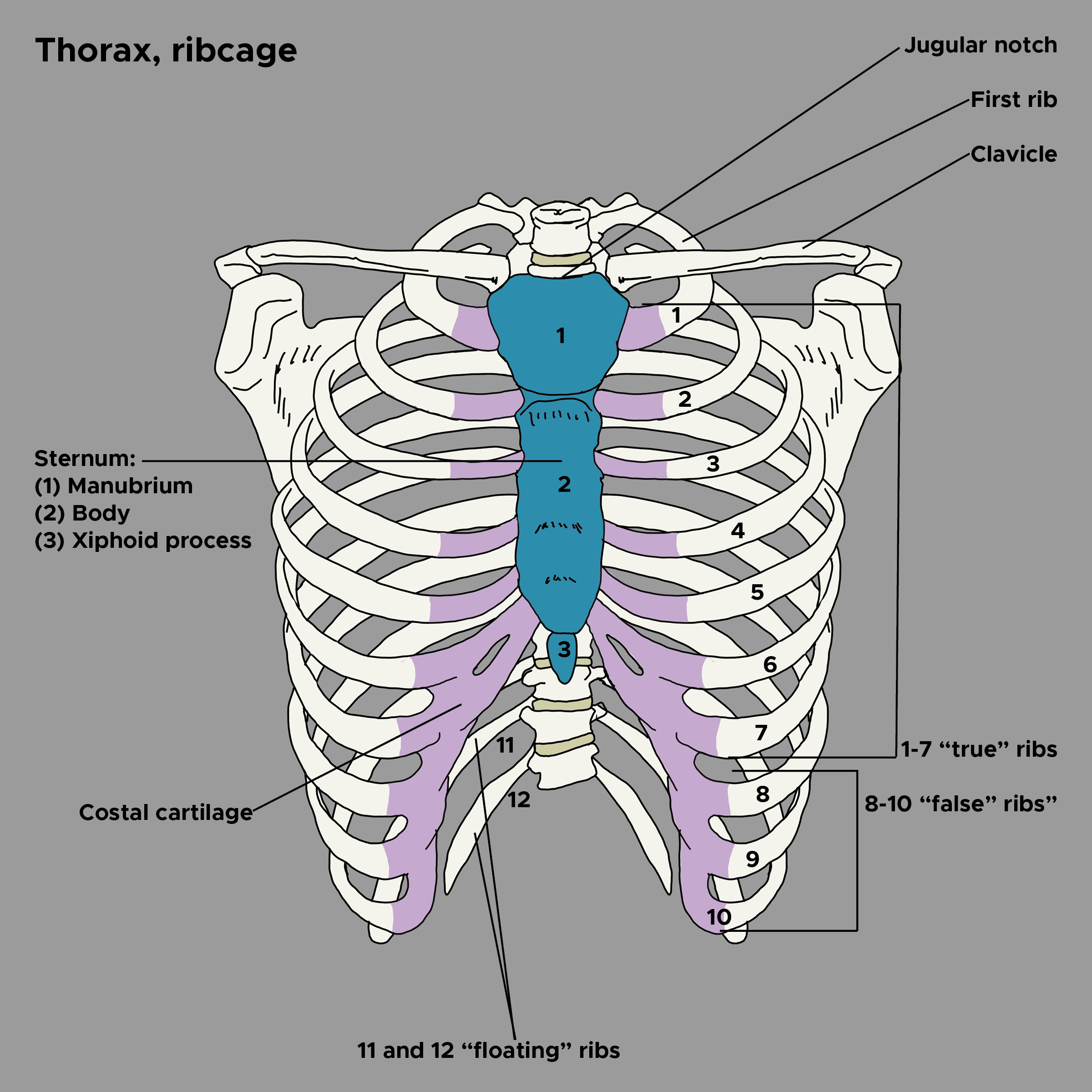

The chest wall consists of the ribs, costal cartilages, and sternum (see Image. Thoracic Bones and Cartilage). The rib cage protects the thoracic organs while allowing for respiratory movements. Of the 12 rib pairs, the first 7 are true ribs, articulating directly with the sternum via their costal cartilages. The rest are false rib pairs, with pairs 8 to 10 attaching indirectly to the sternum via cartilage connections to the ribs above them. Pairs 11 and 12 are "floating ribs," having no sternal attachment.[1] The sternum (breastbone) is a flat bone situated in the center of the anterior chest wall. This bone consists of the manubrium, body, and xiphoid process.

Costochondral junctions, where the costal cartilages articulate with the sternum, are crucial in costochondritis pathophysiology. These junctions are composed of hyaline cartilage, which is susceptible to inflammation.

Etiology

Costochondritis arises from localized costochondral joint inflammation, leading to pain. The condition is idiopathic, though costochondritis may also arise from infection, repetitive trauma, seronegative spondyloarthropathies, thoracic tumors, intravenous drug abuse, and rheumatologic disorders.[2]

Epidemiology

The epidemiology of costochondritis is not well-established, though the condition is estimated to occur in 4% to 50% of patients with chest pain. A 1994 study showed a higher frequency of costochondritis in female patients. Costochondritis was the diagnosis in 36 cases (30%) in a group of 122 individuals presenting to the emergency department with chest pain not due to malignancy, fever, or trauma.[3] Another study of noncardiac chest pain showed that 45% of 1,300 emergency room visits for chest pain had a musculoskeletal cause.[4] A meta-analysis of 15,000 ER visits found that 16% of patients had musculoskeletal chest pain.[5] In contrast, within the ambulatory setting, approximately 33% to 47% of patients with chest pain have a musculoskeletal origin.[6]

Costochondritis most commonly affects adults aged 40 to 50 years. Thus, the condition can mask cardiac pathology. Chest pain in adolescents presenting to an outpatient clinic is frequently attributed to musculoskeletal causes (31%), with costochondritis comprising 13% of the cases.[7]

Pathophysiology

The pathophysiology of costochondritis is poorly understood. The condition may be precipitated by vigorous activity of the upper extremities, coughing, or strenuous activity. Costochondritis may also be related to an underlying inflammatory musculoskeletal condition. The condition primarily affects the anterior chest wall, often involving the 2nd to 5th costochondral junctions, although any junction can be affected.[8]

History and Physical

History

Patients with costochondritis commonly report pain in the upper anterior chest wall that worsens with movement, including deep breaths, coughing, and stretching. The pain quality varies, though it may be described as sharp or dull.

As with any undifferentiated symptom, the history of present illness, past medical history, social history, family history, and a review of systems are very important to understand the risk for more common but serious chest pain presentations. The timing, onset, severity, location, radiation, and associated symptoms that can point to an alternative diagnosis should be noted. Costochondritis can mimic acute coronary syndrome, pulmonary embolism, aortic dissection, pneumonia, esophageal injury, pneumothorax, and trauma, which must all be ruled out. Factors that provoke or improve pain should also be elicited.

Physical Examination

The physical exam should focus on the chest wall, including the heart, lungs, neck, skin, and thorax. The skin should be examined carefully for abnormalities like rashes and swelling that may indicate an alternative diagnosis, such as Herpes zoster. The sternum and sternoclavicular joints should be examined for warmth, swelling, or erythema, which should be absent in costochondritis and may suggest a different clinical entity.

Chest wall pain due to costochondritis is usually reproducible by mild-to-moderate palpation at the upper costochondral junctions. Often, point tenderness is elicited where 1 or 2 ribs meet the sternum. However, a pitfall of the typical costochondritis physical findings is that pain due to acute coronary syndrome is occasionally described as reproducible.[9]

Other exam maneuvers described for eliciting costochondritis symptoms are the "crowing rooster" and "horizontal arm flexion."[10][11] The crowing rooster maneuver entails the patient extending their neck toward the ceiling from a seated position while the examiner exerts gentle traction on the upper arms by pulling them backward and superiorly. Horizontal arm flexion can be performed by having the patient flex an arm anteriorly to the chest while rotating the head toward the ipsilateral shoulder. The examiner then applies steady, prolonged horizontal traction. The same maneuver should be done with the opposite arm.

Patients with costochondritis present with normal vital signs. Tachycardia or hypotension should raise suspicion of an alternative diagnosis as the cause of the patient's chest pain.[12]

Evaluation

Diagnostic testing is mainly indicated to rule out other potential etiologies of chest pain, such as myocardial infarction or pneumonia. Testing should be selected based on patient age, clinical features, and risk factors for other causes. The American College of Rheumatology recommends that a chest x-ray be considered in all patients with chest pain to rule out conditions like pneumonia, spontaneous pneumothorax, and lung masses.[13] Additional cost-effective imaging for chest pain includes point-of-care ultrasound, which can detect fractures. Further imaging is not recommended to diagnose costochondritis, though it may be considered to rule out serious conditions with similar presentations. An electrocardiogram (ECG) should be considered in all adult patients with anterior chest pain to rule out cardiac abnormalities. Chest x-ray and ECG are normal in costochondritis.[14]

Treatment / Management

Costochondritis is benign and self-limited. Treatment is primarily supportive, aiming to relieve symptoms. Topical modalities include heat and topical medications such as capsaicin, diclofenac gel, and lidocaine patches. Oral NSAIDs or acetaminophen may also be considered.

A small study showed that physical therapy involving a stretching program benefits patients with pain refractory to other methods.[15] Meanwhile, localized corticosteroid injections at the costochondral junction have insufficient evidence and thus should only be considered for people unresponsive to more conservative treatments. Acupuncture has not been rigorously evaluated, though a small case series showed it could improve chronic pain lasting 12 months.[16]

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis of costochondritis can be characterized into 3 broad categories that can all cause chest pain: intrathoracic and chest wall pain syndromes and systemic disorders that can cause chest wall pain.

Intrathoracic Syndromes

- Acute coronary syndrome: Consider this condition in a patient presenting with any chest pain. Important differentiating risk factors for this disease are age, family history, lifestyle factors like tobacco use, and preexisting diabetes, hypertension, and coronary arterial disease.

- Pericarditis: Consider this disorder in patients with acute onset of positional chest pain that improves by sitting forward and worsens by laying supine. Pericarditis may be idiopathic, preceded by a recent viral illness or postcardiac surgery, or associated with an underlying connective tissue disorder like lupus.

- Pneumothorax: Consider this condition in patients with chest pain, shortness of breath, and acute distress. Risk factors include antecedent trauma, prior pneumothorax history, collagen vascular disorders such as Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, emphysema, and recent chest procedures.

- Pneumonia: Consider this disease in patients with chest pain, dyspnea, cough, and fever. Risk factors include advanced age and immunosuppressive states such as diabetes, chronic kidney disease, dialysis dependence, immunosuppressive medication intake, drug or alcohol use, and malnutrition.

- Aortic dissection: Consider this condition in patients with chest pain radiating to the arm or back and accompanied by asymmetric limb blood pressures. Risk factors include hypertension and coronary artery disease. A chest computed tomography angiogram (CTA) may be obtained if a dissection is suspected based on history, exam findings, or the presence of a widened mediastinum on a chest x-ray.

- Pulmonary embolism: Consider this disorder in patients with chest pain and dyspnea. Risk factors include a history of malignancy, recent travel, recent surgery or injury, personal history of pulmonary embolism or deep vein thrombosis, tobacco use, and oral contraceptive intake. The Wells score with a d-dimer may be employed in low-risk patients with suspected pulmonary embolism.[17] Imaging tests, such as a ventilation-perfusion scan or chest CTA, are indicated in high-risk individuals.

- Esophageal perforation: Consider this injury in patients with acute or severe chest pain. Risk factors include recent gastrointestinal procedures like endoscopy, acute protracted vomiting, alcohol use disorder, and thoracic conditions like lung cancer.

- Gastroesophageal reflux disease: Consider this condition in patients with chest pain that worsens after eating or lying recumbent. Other manifestations include regurgitation, bloating, globus sensation, and hoarseness. Symptoms may improve immediately with antacid intake ingestion.

Chest Wall Conditions

- Sternoclavicular, sternomanubrial, or shoulder arthritis or destructive costal cartilage lesions due to an infection or neoplasm: These disorders usually cause localized pain and may be associated with visible swelling, redness, or warmth.

- Painful xiphoid syndrome: This condition causes localized discomfort on xiphoid process palpation.

- Herpes zoster: Skin examination may reveal erythema or vesicular lesions in a dermatomal pattern on the chest wall. Pain is often neuropathic and severe.

- Slipping rib syndrome: This disorder presents with abdominal or lower chest wall pain, costal margin tenderness, and pain on palpation of the area.

- Tietze's syndrome: Tietze's syndrome often causes localized costosternal, sternoclavicular, or costochondral joint swelling, usually in the area of the 2nd and 3rd ribs.

- Traumatic muscle pain and overuse myalgia: This condition is precipitated by exercising the upper extremities vigorously during occupational or sporting activities. Patients may have a history of trauma to the area.

Systemic Disorders

- Fibromyalgia: Patients may exhibit chest pain but commonly experience chronic and longstanding pain across multiple body areas. Fatigue, sleep disturbance, and mood disorders may also be noted.

- Ankylosing spondylitis: This disorder presents with costovertebral, costotransverse, and thoracic apophyseal joint inflammation. Patients may have morning back stiffness, poor spinal mobility, and sacroiliac joint inflammation or fusion signs on pelvic x-rays.

- Psoriatic arthritis: Inflammation may involve the chest and cause pain. Extremity joint swelling and characteristic skin lesions are usually present.

- Synovitis, acne, pustulosis, hyperostosis, and osteitis (SAPHO) syndrome: Patients have arthritis of the anterior chest wall with sterile osteomyelitis, hyperostosis, palmoplantar pustulosis, acne, and peripheral or axial arthritis.

- Systemic lupus erythematosus: Patients with lupus may present with chest pain due to pleural or pericardial inflammation, pulmonary embolism, myocardial infarction, fibromyalgia, or costochondritis related to their disease.

- Panic disorder: Consider this condition in patients with chest pain accompanied by nonspecific symptoms, including arm and leg pain or other abnormal sensations, dizziness, a sense of doom, palpitations, and dyspnea. A history of anxiety may be elicited. The condition may or may not have a precipitating event.

A complete clinical evaluation and relevant diagnostic tests can distinguish costochondritis from these conditions. Ruling out life-threatening conditions is a priority before initiating treatment.

Prognosis

Costochondritis is a self-limited condition. Over 90% of patients experience symptomatic improvement within 3-4 weeks.

Complications

Costochondritis is a self-limited condition. A small percentage of patients may present with refractory or recurrent costochondritis, warranting a rheumatology referral to search for systemic chest pain causes and possibly explore minimally invasive interventions like corticosteroid injections.

Deterrence and Patient Education

Primary preventive measures for costochondritis involve promoting habits that reduce chest wall strain. Educating individuals about maintaining proper posture and avoiding activities that exacerbate symptoms, such as heavy lifting or repetitive movements, can help prevent costochondral junction inflammation. Additionally, stress management and regular, low-impact exercises that strengthen the chest muscles while minimizing strain can contribute to overall symptom control and reduce the likelihood of recurrent episodes. Addressing underlying conditions like rheumatological disorders or respiratory infections may also prevent costochondritis.

For secondary prevention, patients must be educated on the factors that can exacerbate the pain, including sneezing, coughing, and overuse activities. Patients must be reassured that costochondritis is benign and often resolves on its own. Adherence to prescribed treatments must also be emphasized. Patients should be instructed to return for additional evaluation if they develop worsening chest pain, shortness of breath, dizziness, syncope, or visible chest lesions, including swelling and rash.

Pearls and Other Issues

Costochondritis is a diagnosis of exclusion. Chest pain etiologies associated with increased morbidity and mortality must first be ruled out before committing to this diagnosis. Patients typically present with positional upper chest wall pain without associated symptoms such as shortness of breath, dizziness, nausea, and headache. Pain may be reproducible on a physical exam without vital sign abnormalities or visible chest lesions, such as swelling or rash.

Diagnostic testing must be guided by the presence of risk factors for life-threatening conditions. Labs, ECG, and chest x-ray should be normal if ordered. Advanced imaging such as CTA may be needed to rule out serious pathology.

Costochondritis is a self-limited condition. The standard of care is treatment with topical medications and oral NSAIDs. Refractory cases may be referred for physical therapy, acupuncture, or rheumatology evaluation for possible corticosteroid injections.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Costochondritis is a diagnosis of exclusion, though it may be helpful to involve specialists when ruling out other chest pain causes. While emergency or primary care physicians often complete the initial chest x-ray and ECG interpretation, radiologists and cardiologists may complete the official diagnostic test report. Questionable ECG findings should be discussed with a cardiologist or electrophysiologist before diagnosing a patient with costochondritis.

Refractory cases must be referred to a rheumatologist, physical therapist, or both to improve the pain outcomes. A gastroenterology, neurology, pulmonology, or cardiology referral should be considered when suspecting visceral pathology as the cause of pain. Remember that costochondritis may also arise from intrathoracic disease.[18][19]