Continuing Education Activity

Cleft lip repair is a surgical procedure that may be approached with a wide array of different techniques. The ultimate goal of cleft lip repair is to restore the sphincter function of the orbicularis oris muscle and obtain a cosmetically favorable outcome for the developing child. This activity reviews the most commonly used surgical techniques and highlights the importance of a multidisciplinary team in these complicated patients that include an otolaryngologist, a plastic surgeon, a dentist, an orthodontist, a pediatrician, a geneticist, a nurse, a social worker, and a speech-language pathologist.

Objectives:

- Discuss the goals and timing of cleft lip repair.

- Identify the surgical considerations for cleft lip repair.

- Describe the most common surgical techniques for unilateral and bilateral cleft lip repair.

Introduction

Cleft lip deformity is one of the most common congenital malformations.[1] It may be isolated, or it may be associated with other malformations. Management of the cleft lip patient is centered around a multidisciplinary approach. Ultimately, cleft lip requires surgical intervention for definitive repair for which many surgical techniques have been described. Preoperative and postoperative strategies aid in the successful management of patients with this disorder. The choice of the surgical technique employed depends on many factors such as surgeon preference, the severity of the deformity, and the presence or absence of other deformities. In this discussion, we aim to present the most commonly used surgical techniques for cleft lip repair, their advantages, and their disadvantages.

Anatomy and Physiology

In order to appreciate the anatomy of cleft lip deformity, it is vital to have a thorough understanding of the embryology behind this disorder. The first pharyngeal arch begins to develop facial prominences around the fourth week of embryonic development. These structures are the maxillary prominences, derived from neural crest cells, and the nasal placodes, derived from surface ectoderm. Around the fifth week of embryonic development, the nasal placodes invaginate, forming the nasal pits, creating a ridge of tissue around the pits called the lateral nasal prominence at the lateral aspect and the medial nasal prominence at the medial aspect. During the sixth to seventh weeks of embryonic development, the bilateral maxillary prominences grow medially towards the medial nasal prominences, and fusion occurs, leading to the formation of the upper lip. The fusion of the bilateral medial nasal prominences forms the medial portion of the upper lip, whereas the paired maxillary prominences form the lateral aspects of the upper lip. Further medial growth of the maxillary prominences leads to additional fusion of the deep medial nasal prominences, which creates the primary palate. The primary palate includes the four incisors and the palate anterior to the incisive foramen. Additionally, the medial nasal prominences form the philtrum, the columella, and the nasal tip. The lateral nasal prominences are involved in the development of the nose and do not contribute to upper lip formation.[2]

Disruption at any of the aforementioned points during upper lip embryologic development leads to cleft lip deformity, unilateral or bilateral. Cleft lip deformity can be further classified into complete and incomplete clefts based on the extent of the deformity. Complete cleft consists of disruption of the entire vertical thickness of the upper lip. It is usually associated with an alveolar defect since the alveolus is part of the primary palate. Incomplete cleft lip involves only a portion of the height of the upper lip and has a segment that is continuous between the two portions of the upper lip. The extent of incomplete cleft lip varies from muscular discontinuity with intact overlying skin to a wide cleft with a thin segment of skin that crosses the cleft, called the Simonart band.

Normally, the orbicularis oris muscle surrounds the lips to form a complete sphincter around the mouth. Patients with cleft lip deformity have orbicularis oris deformities that must be corrected to achieve proper lip and mouth function. Patients with microform cleft lip in which an incomplete cleft involves less than two-thirds of the upper lip usually have an orbicularis oris muscle that connects the medial and lateral segments of the cleft at its upper segment. In contrast, the lower muscle segments insert into the cleft margins. Patients with complete cleft lip deformity have an orbicularis oris muscle that fails to surround the mouth to form a sphincter. In these patients, muscle fibers run along the cleft margins to insert on the columella on the medial segment of the cleft and the nasal ala on the cleft’s lateral segment. Correction of the cleft lip requires detachment of the orbicularis oris muscle’s abnormal attachments and creating a horizontal bridge across the cleft to form a complete sphincter around the mouth. In bilateral cleft lip, the muscle fibers run along the lateral cleft margins to insert on the bilateral nasal alae. In these patients, the medial prolabial segment is usually devoid of muscle tissue, which leads to anterior protrusion of the prolabial segment and primary palate relative to the nasal septum.

When speaking about cleft lip deformity, it is important to also take into consideration the nasal deformity associated with this disorder. Nasal deformity associated with this disorder is caused by traction from the abnormally inserted orbicularis oris muscle and the absent anterior nasal floor.[3]

In unilateral cleft lip, the lower lateral cartilage on the cleft side will have a short medial crus and a long lateral crus in a more caudal position. The columella will be found on the noncleft side. These anatomical abnormalities lead to nasal tip deviation towards the noncleft side with nasal septum deviation towards the noncleft side and a laterally, inferiorly, and posteriorly displaced alar base on the cleft side.

In bilateral cleft lip, lack of orbicularis oris muscle in the prolabial segment causes anterior premaxillary protrusion. This causes the medial crura of the bilateral lower lateral cartilages to be abnormally short and the columellar skin to be deficient, leading to a shortened, almost absent, columella. These findings lead to a broad nasal tip with laterally displaced alae.

Indications

Any patient born with a cleft lip should undergo repair if no contraindications exist.

Contraindications

The following are some contraindications to cleft lip repair:

- Surgery may be delayed in case further workup of coexisting conditions is necessary.

- Conditions that preclude toleration of general anesthesia may delay the surgery.

- Coexisting conditions that require surgery on a more urgent basis, such as cardiovascular anomalies, should be performed prior to cleft lip repair.

Equipment

The procedure requires the following equipment:

- Scalpel

- Ophthalmic scissors

- Tissue scissors

- Mosquito clamps

- Toothed pick-ups

- Non-toothed pick-ups

- Double-pronged skin hooks

- Ruler

- Sterile marker

Personnel

The following personnel are needed:

- Surgeon

- Surgeon's assistant

- Operating room technician

- Registered nurse

- Anesthesiologist

- Anesthetist

Preparation

Although some have proposed surgical correction of the cleft lip as early as 48 hours after birth, surgical repair is generally performed following the rule of 10s, which states that the timing should be performed at 10 weeks of age, when the patient weighs 10 lbs. and when hemoglobin is at 10 g/dL.[4] Repair between 2 to 3 months of age allows the patient to be adequately evaluated for other congenital anomalies and for the patient to grow, giving additional tissue for repair.

Before definitive surgical repair, techniques may be employed that facilitate surgical intervention, especially for wide clefts. The most widely used techniques are tape adhesion and orthopedic appliances.[5] The primary goal of presurgical techniques is the narrowing of the cleft to minimize lip tension after repair and improve outcomes. Tape adhesion consists of the application of steri strips across the cleft to achieve this goal. Orthopedic appliances, also termed nasoalveolar molding, consists of wearing a palatal appliance constructed by an orthodontist. This palatal appliance brings the alveolar arches closer together and narrows the cleft. The palatal appliance is gradually changed over weeks to months to optimize cleft width for surgery.

Technique or Treatment

The two most commonly used surgical techniques for the repair of the unilateral cleft lip, and the ones that will be discussed here, are the rotation-advancement technique, also called the Millard technique, and the triangular flap technique, also known as the Tennison-Randall technique.[6][7]

The rotation-advancement technique was first described by Millard and consists of a rotational flap on the cleft’s medial segment and an advancement flap originating from the cleft’s lateral segment. The advantages of this technique include a suture line that recreates the philtrum on the cleft side; access to nasal tip cartilages allowing nasal reconstruction; and allows intraoperative adjustment. Disadvantages have potential nostril stenosis, difficulty closing wide clefts, and increased difficulty for the inexperienced surgeon as the technique requires ample intraoperative judgment for flap modification as the surgery progresses.[8][9] The triangular flap technique was first described by Tennison and consists of a triangular flap originating from the cleft side inserted on an incision performed on the noncleft side. This technique's primary advantage is that it’s based on carefully measured and predetermined landmarks that allow the inexperienced surgeon to perform the procedure easily. Additionally, this flap allows wider clefts to be repaired. The disadvantages in this technique are mostly related to cosmetic outcomes and include failure to create a philtrum on the cleft side, a scar that crosses cosmetic subunits, inability to access nasal cartilages during repair, and inability to modify repair once surgery has started.[10]

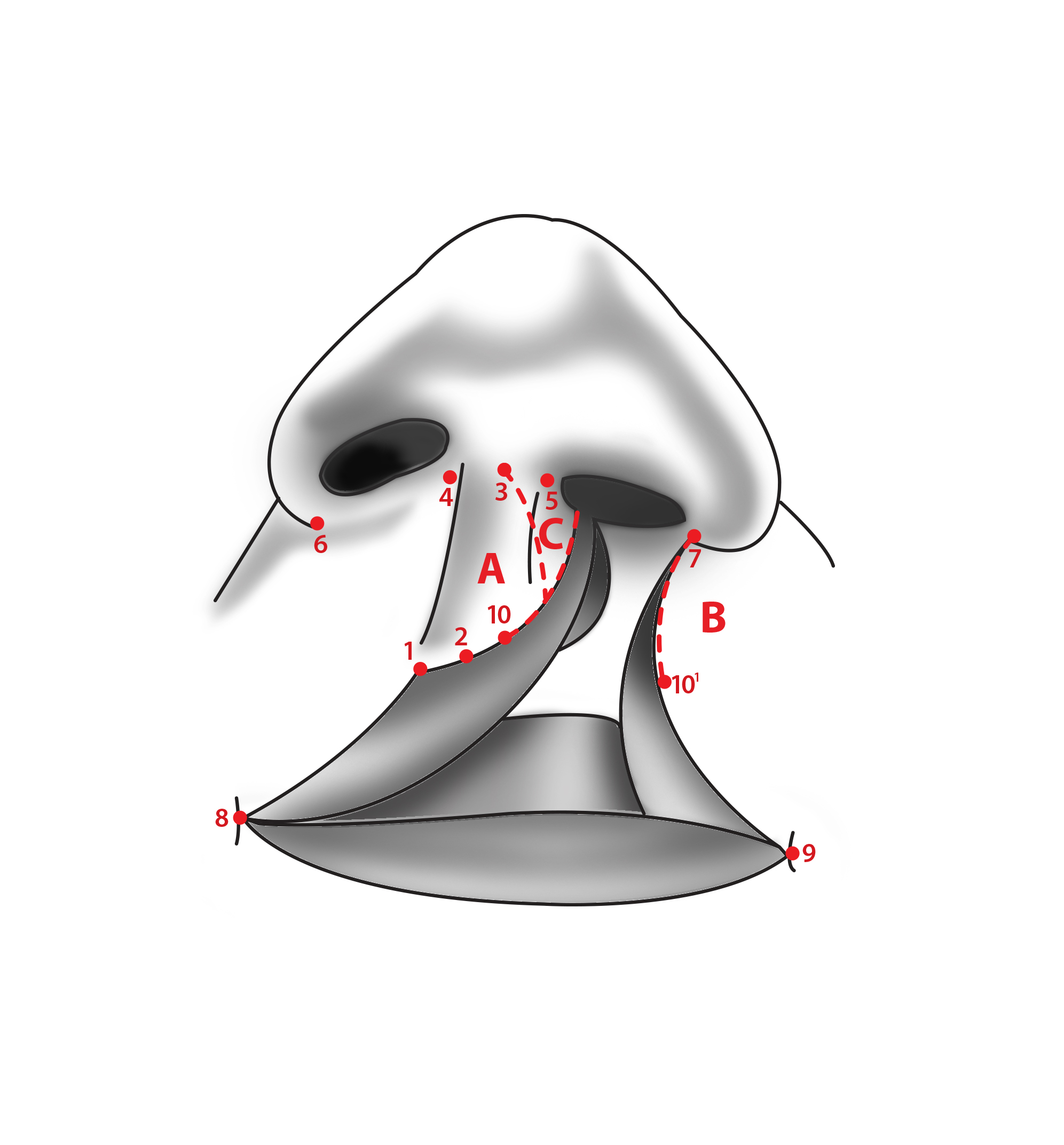

Surgery will be guided by important anatomical landmarks that should be identified before the procedure, regardless of technique (Figure 1). These structures are marked with a marker. Structures that must be marked are: the noncleft side’s Cupid’s bow peak (1), the midpoint between both Cupid’s bow peaks (2), the midpoint of the columella (3), the base of the columella on the noncleft side, and cleft side (4 and 5), nasal ala base on the noncleft side and cleft side (6 and 7), and the oral commissure on the noncleft side and cleft side (8 and 9). After these structures are identified, other landmarks necessary for proper surgical planning may be determined. The peak of Cupid’s bow on the medial cleft side (10) is determined by measuring the distance from the noncleft side’s Cupid’s bow peak to the midpoint between both Cupid’s bow peaks. This distance equals the distance between the midpoint between both Cupid’s bow peaks and the cleft side’s Cupid’s bow peak on the medial segment of the cleft. The Cupid’s bow peak on the lateral cleft margin (10’) is determined by measuring the distance from the noncleft side oral commissure to the noncleft side Cupid’s bow and marking a point at the same distance on the lateral cleft margin from the cleft side’s oral commissure. These two points, the medial cleft margin Cupid’s bow peak and the lateral cleft margin Cupid’s bow peak, are essential in creating continuity in the vermilion border during repair and are tattooed with a needle with gentian violet or methylene blue before surgery.

After repair, the incisions are kept clean and free of crusting by cleaning with hydrogen peroxide and applying antibiotic ointment. Elbow splints are used for 3 weeks to prevent the patient from bending arms and touching surgical wounds. During the first postoperative week, arm restraints are also used. Feeding is done by a bulb syringe for 3 weeks. Sutures are removed after the first postoperative week. Antibiotic prophylaxis with a penicillin antibiotic is given during the first 5 postoperative days.

Millard Rotational-Advancement Technique

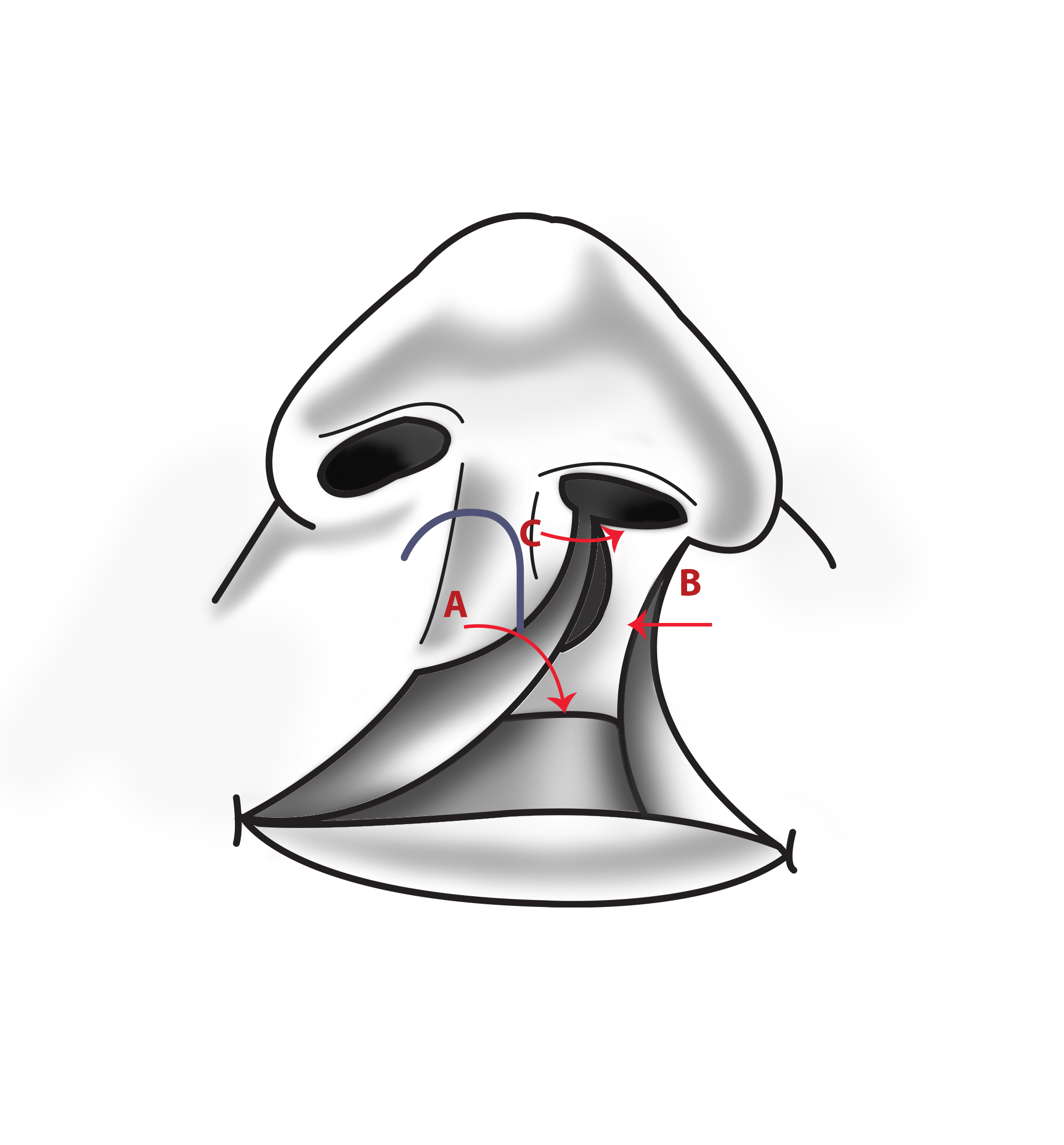

Before starting the procedure, the anatomical landmarks described above should be identified and marked. After identifying the proper anatomical landmarks, the incisional lines should be outlined (Figure 2). The first incisional line will form the medial cleft segment rotational flap. This line extends from the Cupid’s bow peak on the medial cleft margin superiorly along the vermilion border and then curves medially towards the base of the columella (point 10 to point 3). A second incisional line should be marked, which continues along the medial cleft margin’s vermilion border from the point the first incisional line leaves the vermilion border and extended towards the nasal floor. This creates what is called a c-flap, which may be utilized to extend the columella on the cleft side when required (Figure 3). The incision which will form the lateral advancement flap should then be traced. This incision will extend from the Cupid’s bow peak on the cleft’s lateral margin superiorly along the vermilion border towards the nasal floor (From point 10 to point 7). Another incision line is then traced on the lateral cleft margin from the junction of the ala with the lip towards the lateral alar margin, following the alar margin horizontally and then vertically.

After the proper anatomical landmarks are identified and the incisional lines traced, repair may be performed as follows:

- A curvilinear incision is made from the cleft side’s Cupid’s bow peak on the medial cleft margin towards the base of the columella. This incision should involve the skin only.

- An incision is made from the cleft side’s Cupid’s bow peak on the medial cleft margin towards the nasal floor along the vermilion border. This incision involves the skin and subcutaneous tissue, leaving the oral mucosa intact.

- An incision is performed on the lateral cleft margin extending from the cleft side’s Cupid’s bow peak on the lateral cleft margin superiorly to the nasal floor along the vermilion border. This incision should be through and through involving the skin, subcutaneous tissue, and mucosa.

- The orbicularis oris muscle is exposed by undermining the skin from the underlying muscle 1 cm from the incision margins in both the medial and lateral cleft segments. Undermining of the oral mucosa from the overlying muscle must also be done using the same distance from the incision margins.

- The orbicularis oris muscle’s abnormal attachments to the base of the columella on the medial cleft margin and the alar base on the lateral cleft margin are transected to create bilateral muscle flaps.

- The skin is dissected off of the columella, and dissection is directed in a cephalad direction between both medial crura of the bilateral lower nasal cartilages to gain access to the nasal dome and elevate the skin off of the dome.

- The nasal ala on the cleft side is detached from the underlying maxilla, and the skin is elevated off of the lower cartilage’s lateral crus on the cleft side. The nasal mucosa is also dissected off of the lower cartilage’s lateral crus on the cleft side.

- A skin hook is used for upward retraction of the skin overlying the dome of the cleft side’s lower nasal cartilage. At this moment, the medial cleft margin’s c-flap may be sutured to the medial cleft incisional margin to elongate the columellar skin on the cleft side (Figure 4).

- The medially-based rotational flap is rotated inferiorly, and the laterally-based advancement flap is extended medially. The closure is assessed to determine if additional rotation will be necessary to close the defect. If rotation is insufficient, a back-cut may be performed at a perpendicular angle inferiorly from the columellar base margin of the incision performed in step 1.

- After adequate closure of both flaps is confirmed to be possible, the bilateral muscle flaps created in step 5 may be rotated inferiorly and sutured together with interrupted sutures.

- A traction suture is placed between the medial cleft segment Cupid’s bow peak and the lateral cleft segment Cupid’s bow peak.

- The deep portion of the superior medial part of the lateral advancement flap is sutured to the anterior nasal spine. This suture anchors the lateral advancement flap.

- The bilateral nasal mucosal flaps obtained from the extension of the incisions along the vermilion border into the anterior nasal floor are sutured with interrupted chromic sutures to close the anterior nasal floor. During this step, it is important to pay attention to the possible narrowing of the nostril on the cleft side. If this occurs, an elliptical incision may be performed at the lateral alar margin of skin only, and the skin removed—this aids in achieving more anterior positioning of the retroplaced nasal ala.

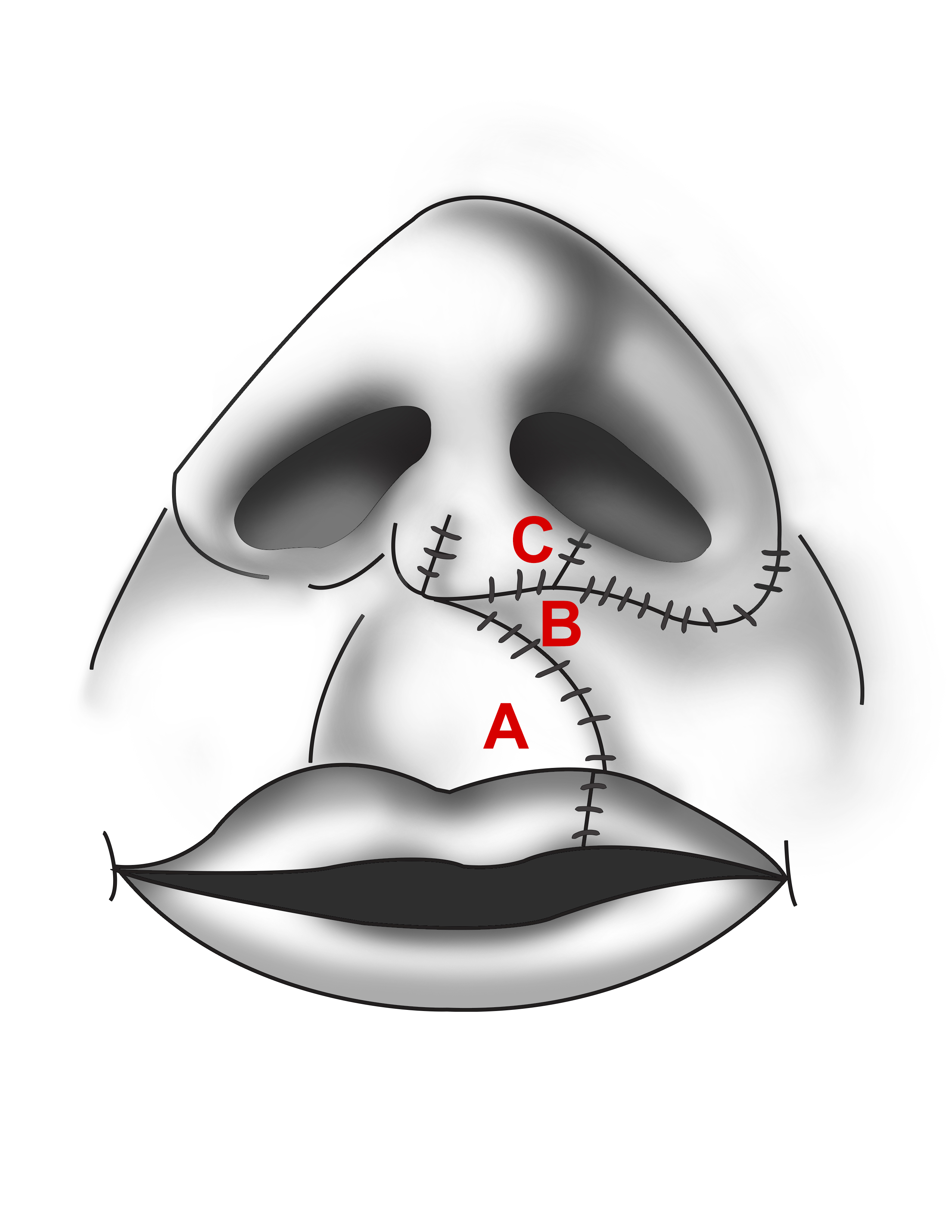

- The skin is closed with interrupted nylon sutures (Figure 5).

- The vermilion and the vermilion border are then closed with interrupted nylon sutures on the outer surface and with interrupted chromic sutures on the inner surface.

- The oral mucosa is closed with interrupted chromic sutures.

- A bolster is placed at the cleft side’s nostril to stabilize the repaired anterior nasal floor and avoid nostril stenosis.

Tennison-Randal Triangular Flap Technique

Prior to beginning the procedure, the same anatomical landmarks described for the Millard technique should be identified and marked. Additionally, surgical planning must be done with extreme care since this technique allows for little intraoperative modification. Surgical planning starts with identifying the length the lip must cover. This is done by calculating the difference between the base of the columella and Cupid’s bow peak on the noncleft side and the base of the columella and Cupid’s bow peak on the cleft side’s medial margin (Figure 6). The result of this difference is the number of millimeters the lip must be lengthened [(A to B) – (C to D) = Cleft width]. To account for scar contracture, 2 mm should also be added to this result. When this distance is greater than 6 mm, a two-triangular flap technique should be employed with a laterally-based inferior triangular flap and a medially-based superior triangular flap.[11] The incisions to be performed are then outlined, starting with the laterally-based triangular flap (Figure 7). This incision line starts from the Cupid’s bow peak on the lateral margin of the cleft and extends superiorly along the vermilion border the length that the lip must be lengthened up to a maximum of 6 mm. A line that is the same length as the first line is then drawn perpendicular to the vermilion border. The distance from point A to point B equals the distance from point B to point C, which in turn equals the distance from point C to point A, creating an equilateral triangle flap. An incisional line that is the same length as these lines are then drawn perpendicularly from Cupid’s bow peak on the cleft side’s medial margin. This is where the laterally-based triangular flap will be inserted. If a two-triangular flap technique is to be employed, the superior, medially-based triangular flap is traced starting with a line perpendicular to the superior medial cleft margin vermilion border that will be directed towards the base of the columella, and its length will be the additional amount of millimeters required beyond the initial 6 mm. The other side of the equilateral triangle is traced from the point this line meets the vermilion border superiorly towards the nasal floor. The contralateral incision line where this triangle will be inserted is traced perpendicularly from the vermilion border at the junction of the alar border and the upper lip.

After the surgical incisions are properly measured and outlined, the surgery may begin using the following steps:

- An incision is performed on the medial cleft margin from the medial cleft Cupid’s bow peak to the anterior nasal floor along the vermilion border. This incision is made through the skin and subcutaneous tissue; the oral mucosa is left intact (Figure 8).

- An incision is made from the medial cleft of Cupid’s bow peak to point B’. This incision is through the skin only. If a second triangular flap is to be used, the incision on the medial cleft margin from the vermilion border to point E is performed in this step as well and is through the skin only.

- On the lateral cleft margin, a through-and-through incision is performed from the lateral cleft Cupid’s bow peak superiorly to the anterior nasal floor along the vermilion border.

- An incision is made from point B to point C that is through the skin only.

- A curvilinear incision extended superomedially from point C to join the vermilion border is performed and is through the skin only. This will create a triangular piece of skin medial to the incision that is discarded.

- The orbicularis oris muscle is dissected free from the overlying skin and underlying oral mucosa on both cleft margins, a distance of 1 cm from the margins.

- The attachments of the orbicularis oris muscle to the base of the columella and the alar base are transected.

- The alar base on the cleft side may be dissected from the maxilla if repositioning of the ala is desired.

- The nasal mucosa is dissected free from the septum and from the cleft side’s lower lateral nasal wall to create the flaps necessary to develop the anterior nasal floor. These flaps are then sutured together with interrupted chromic sutures.

- The cleft side’s nasal ala may be sutured to the anterior nasal spine with a polyglactin suture and tightened until the ala reaches the desired position.

- The bilateral orbicularis oris muscle flaps created in step 7 are rotated inferiorly and sutured with interrupted polyglactin sutures to repair the muscular sphincter.

- A nylon suture is used to approximate the medial and lateral cleft of Cupid’s bow peaks.

- The triangular flaps are inserted into the proper positions, and a nylon corner suture is used between points B and B’ and points D and D’ if a second triangular flap was used.

- The upper lip skin is then sutured with interrupted nylon sutures.

- Interrupted nylon sutures are used to approximate the external surface of the vermilion.

- Interrupted chromic sutures are used to approximate the internal surface of the vermilion and the oral mucosa (Figure 9).

Bilateral Cleft Lip Repair

Bilateral cleft lip repair poses additional difficulty when compared to unilateral cleft lip repair. Different surgeons have different techniques ranging from 2-stage surgical repairs to single-stage surgical repair. Some surgeons employ the triangular flap technique as a single-stage or a 2-stage procedure. Here, we will discuss the single-stage repair introduced by Millard.[12][13]

The most difficult part of bilateral cleft lip repair is managing the premaxilla, which may be anteriorly and sagitally displaced to either side as a result of it being attached only to the nasal septum, and the prolabium, which may be too small to provide sufficient tissue for cleft repair. These challenges can be handled by different methods, which include performing surgical lip adhesion before definitive surgical repair of bilateral cleft lip, using presurgical orthopedic prostheses or surgical procedures to bring the premaxilla to a more inferior and posterior position.

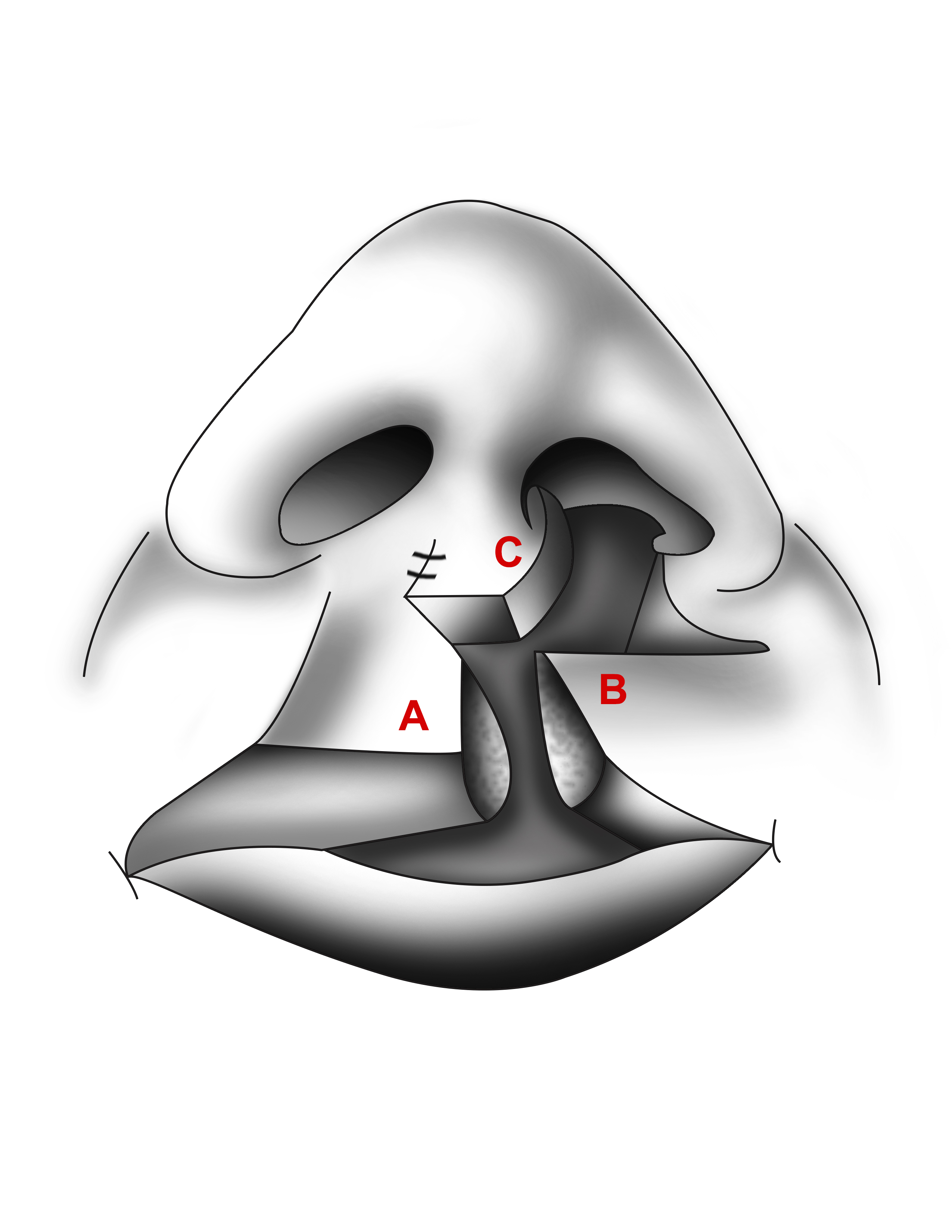

As with unilateral cleft lip repair, identifying anatomical landmarks and outlining surgical incisions are important prior to beginning surgery (Figure 10). First, the midline of the prolabium is identified (point 1). Two symmetrical incision lines are traced in the prolabium, these incisions begin just medial to the base of the columella and continue inferiorly until they reach the vermilion border, diverging laterally a small amount. The upper lip's vertical height will be determined by the length of these incision lines on the prolabium, not by the lateral lip segments. If a marked discrepancy exists, the height of the lateral lip segments may be adjusted by the excision of crescent-shaped segments of skin under the alar bases on the lateral lip segments. Incision lines on the lateral lip segments are traced beginning at both alar bases and extending inferiorly along the vermilion border a distance equal to the prolabium incisional lines (line 2-3 equals line 4-5, which equals line 6-7, which equals line 8-9). Incisional lines are drawn across the bilateral lip segment vermilion that will create flaps D and E that will contain vermilion, mucosa, submucosa, and orbicularis oris muscle. The lateral alar bases are marked to trace incision lines along the alar bases. After outlining incision lines, surgery may be performed using the following steps:

- Incisions 2-3 and 4-5 are performed on the prolabium, creating the prolabial flap (A) and bilateral forked flaps (B and C).

- On the prolabium, incisions may be extended inferiorly into the vermilion, and a horizontal incision may be performed across the vermilion border (3-5) to create flap H that may be used to add volume to the vermilion if whistle deformity occurs.

- Incisions 6-7 and 8-9 are performed on the lateral lip segments along the vermilion border.

- Flaps D and E are created on the lateral lip segments by incisions across the vermilion.

- Circumalar incisions 6-12 and 8-13 are performed. The lateral lip segments are dissected from the maxilla to allow medial advancement. The nasal alae are freed from the maxilla to allow medial advancement.

- The tips of the nasal ala are brought medially and sutured to the area of the anterior nasal spine to achieve symmetric nostrils.

- Excess vermilion in the prolabium is excised and sutured to the premaxilla to provide midline upper lip volume.

- The upper edges of the lateral lip flaps (F and G) are brought to the midline and sutured to the area of the anterior nasal spine inferior to where the nasal alae were sutured. These flaps are not sutured to one another to allow space for the prolabial flap A.

- Orbicularis oris muscle found in flaps D and E is brought midline and sutured to create the muscular sphincter.

- The prolabial flap is lowered, and a suture is placed from its undersurface to the orbicularis oris muscle to create a philtral dimple.

- The bilateral forked flaps B and C are sutured to the lateral anterior nasal walls to create the bilateral anterior nasal floors.

- The skin and mucosa are sutured to finish the repair.

- If a central vermilion deficiency occurs leading to whistle deformity, flap H may be tucked between the prolabial flap A and the bilateral vermilion flaps D and E to add volume to the central vermilion.[14]

Complications

The complications related to surgical repair are wound dehiscence, scar contracture, scar hypertrophy, and infection. Other complications are related to lip and nasal deformities not resolved during the primary repair, such as vermillion notching, misalignment of the white roll, orbicularis discontinuity, short or excessive length of the lip, short or deviated columella, the horizontal orientation of the nares, abnormalities of nostril size, and disturbance of alar base position.

Avoiding tension at closure and postoperative local wound care will decrease the incidence of wound dehiscence. Careful marking and approximation of the white roll are necessary to avoid its misalignment. Careful orbicularis muscle dissection and suturing are also necessary to avoid orbicularis muscle discontinuity. Prevention is as always therefore the best course of action to avoid complications.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

The standard of care for a patient with cleft lip involves a multidisciplinary team that meets multiple times each year to discuss patient management. This team should be comprised of an otolaryngologist, a plastic surgeon, an oral and maxillofacial surgeon, a speech-language pathologist, an orthodontist, a dentist, a pediatrician, a geneticist, an audiologist, nurses, social workers, and a psychologist. Each member of the team provides their expertise to optimize the management of patients that will most likely have disorders associated or due to their cleft lip deformity.[15][16]