Continuing Education Activity

Foot ulceration is among the most common health issues, and its prevalence has increased recently. It is one of the major causes of amputations, particularly in patients with uncontrolled diabetes. The lifetime risk of developing a foot ulcer in patients with diabetes is more than 33%. Diabetic foot ulcer causes a lot of morbidities and accounts for approximately two-thirds of all United States non-traumatic amputations. Infections in these patients are thought to be limb-threatening conditions. This activity outlines and reviews the evaluation, treatment, and management of foot ulceration and reviews the role of interprofessional teams in evaluating and treating patients with this condition.

Objectives:

Review the contributing factors and underlying causes of foot ulcerations, including peripheral vascular disease, neuropathy, biomechanical structural deformities, and soft tissue changes.

Describe the evaluation of foot ulceration.

Outline the variety of treatment options for foot ulcerations.

Summarize the interprofessional team approach required for successful healing of foot ulceration.

Introduction

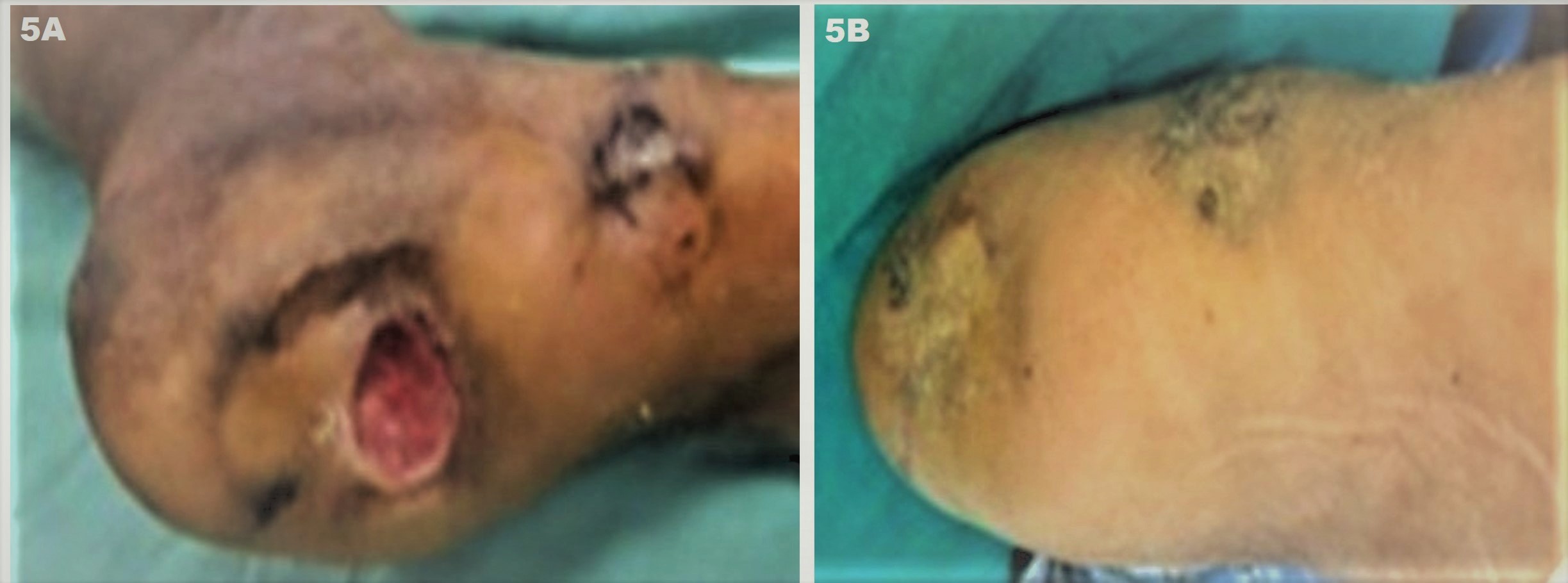

Foot ulceration is among the most common health issues, and its prevalence has increased recently. It is one of the major causes of amputations, particularly in patients with uncontrolled diabetes (see Image. Diabetic Foot Ulcer). The lifetime risk of developing a foot ulcer in patients with diabetes is more than 33%.[1] Diabetic foot ulcer causes a lot of morbidities and accounts for approximately two-thirds of all United States non-traumatic amputations.[2][3][4] Infections in these patients are thought to be limb-threatening conditions.[4]

Etiology

Simultaneous action of multiple contributing factors such as peripheral vascular disease, neuropathy, biomechanical structural deformities, and soft tissue changes is behind the formation and progression of foot ulcerations.[1]

Vasculopathy consists of both macro- and microvascular processes. Cardiovascular, cerebrovascular, and peripheral vascular or arterial disorders are among the macrovascular, and arterioles and capillaries dysfunctions are the microvascular processes. Peripheral arterial disease (PAD) commonly affects the peroneal and tibial arteries. The atherosclerotic plaque begins to expand within the vessel walls, and the occlusion facilitates the healing of ulceration. Diabetes, smoking, hypertension, and hyperlipidemia can contribute to PAD, leading to an increased risk of ulceration. Patients with diabetes mellitus (DM) and PAD are at a higher risk of lower extremity amputations. Hyperglycemia is associated with increased thromboxane A2 (TXA2), a platelet aggregating factor and vasoconstrictor; this increase can lead to a hypercoagulable state and occlusion.[5]

As the capillary size decreases, an increase in vascular permeability and an impairment in the local blood flow regulations alter the microvasculature in patients with DM. Endothelial dysfunction is thought to be the leading cause of changes in the microvascular system. Endogenous nitric oxide causes dilatation of both arteries and veins at the microvascular level by regulating the vascular tone. Vasoconstriction and hypertension occur as the level of nitric oxide decreases. Lower responsiveness of patients with diabetes to nitric oxide puts them at a higher risk of increased vasoconstriction and, subsequently, ulceration due to a lack of adequate nutrients and oxygen for healing.

Peripheral neuropathy is a progressive loss of peripheral nerve fibers, including the sensory, motor, and autonomic fibers. It can progress to a complete sensation loss, which typically begins distally at the toes and advances proximally with a stocking and glove pattern. Patients are not aware of minor traumas at advanced levels of peripheral neuropathy. Motor neuropathy causes a muscle imbalance leading to increased pressure and a tissue breakdown in certain weight-bearing areas. Autonomic neuropathy causes a decreased supply of nutrients and oxygen to the soft tissues of the foot by shunting the arterial blood flow away from the nutrient capillaries. Hyperglycemia is the leading cause of neuropathy in patients with DM. Nitric oxide has also been demonstrated to be decreased in diabetic patients with peripheral neuropathy.

Osseous deformities of the foot play an important role in the development and chronicity of foot ulcers. Structural deformities such as hallux valgus, hammertoes, equinus, hallux limitus, and Charcot foot can lead to an increase in pressure and, thus, ulcerations. A decreased soft tissue density and fat pad atrophy can also predispose patients to lower extremity ulcerations.

Epidemiology

Foot ulceration is a worldwide health-related issue, and its prevalence has increased due to an increase in diabetes. The estimation of global foot ulceration prevalence is more than 6%, which is thought to be higher in males.[6] Ulceration was noted to be more common in patients with type-2 diabetes mellitus versus patients with type-1 diabetes mellitus. Most patients with foot ulcerations were older, had diabetes for a longer duration, and had comorbidities, including hypertension, diabetic retinopathy, higher body mass index, and positive smoking history.

History and Physical

Medical and surgical history should be obtained from the patient, along with social history, allergies, and current medications.

A complete assessment of the ulcer and its surrounding tissue is crucial. Serial wound measurements, biopsy, and cultures are essential for quantitative evaluation of the wound. Qualitative evaluations include visual appearance and odor.[7] A fruity smell, for instance, is associated with pseudomonas infection. In the visual assessment of the wound, we are looking for any possible erythema, edema, fluid discharges, crepitations, or abscess collections. Inspect wound edges for any possible formation of hyperkeratotic tissues, which tends to halt tissue healing. A hyperkeratotic border results from increased stress on the tissue; therefore, the focal pressure should be evaluated. Debridement of hyperkeratotic tissue, which can entrap fluid, is essential to improve wound healing.[7]

Necrotic-base ulcers have a black appearance and are non-viable, indicating a peripheral arterial disease or an infection. Fibrotic-base ulcers have a white to yellowish stringy appearance and tend to halt the formation of the granulation tissue. Granular-base ulcers have a beefy red appearance and indicate a positive healing potential. Wound tracking into sinus tracks should be bluntly probed as it can indicate a deeper infection.[7]

Quantitative measurements should be checked at every clinic visit. Comparing the wound dimensions, including the width, length, and depth over time allows for evaluating the wound contracture. Ulceration discharge cultures can be obtained to target antibiotic therapy in the presence of an infection. A biopsy is performed to rule out any malignant changes in long-standing ulcers.[7]

Evaluation

Ulcer infection should be treated to prompt wound healing. Soft-tissue infections can be examined clinically. Classic clinical signs of an infection are pain, swelling, heat, redness, and loss of function. Systemic symptoms include fever, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, and chills. Laboratory work for cellulitis should include creatinine, bicarbonate, comprehensive metabolic panel (CMP), erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), C-reactive protein (CRP), and complete blood count (CBC) with differential.

Radiographic evaluation is also essential in the overall management of ulcers. X-rays can assist in osteomyelitis assessment or detecting gas gangrene. MR Images are useful in assessing deeper abscess collections and making definitive diagnoses. CT and bone scans can occasionally be used for visualization of bony alterations.[8]

A proper evaluation of the vascular system must be addressed, along with wound care. A clinical vascular assessment includes evaluating the temperature, skin color, skin atrophy, hair distribution, and palpation of pedal pulses, including the posterior tibialis and dorsalis pedis arteries.[8] Doppler ultrasonography is useful in evaluating non-palpable pedal pulses. Ankle-brachial index (ABI) is also a good measure for assessing peripheral arterial flow. ABI of 0.91 to 1.30 is normal, 0.71 to 0.90 indicates a mild PAD, 0.41 to 0.70 indicates a moderate PAD, while 0.4 or less is considered severe.[9]

A magnetic resonance angiography (MRA), arterial duplex ultrasound, or arteriogram can be performed to assess the level and area of vascular occlusion. Clinically, arterial ulcers are painful and develop on the distal extremity. Alternatively, diabetic ulcers tend to be pain-free due to neuropathy and occur on weight-bearing surfaces. Electromyography, along with a nerve conduction velocity test, can be performed to assess peripheral neuropathy.

Radiographic Imaging is essential to rule out the structural deformities in ulcers. A plantar pressure measuring device can detect the peak pressures at specific locations and can be used to identify any underlying bony deformities. The evaluation and treatment of all three Imaging modalities are crucial since any bony deformities in the foot along with a PAD or neuropathy can place a patient at an increased risk of ulcer formation.

Treatment / Management

There are a variety of treatment options for ulcerations. Chronic non-healing ulcers are typically treated with debridement.[10] This can be done surgically, enzymatically, mechanically, or biologically. Mechanical debridement can be performed using a wet to dry dressing, which allows for the non-viable tissues to be removed when changing the dressing.[11] Enzymatic debridement is typically done by the application of collagenase, which helps in the breakdown of collagen.[11] In surgical debridement, use sharp instruments like blades to physically remove the fibrotic and necrotic non-viable tissues.

Offloading to lower the abnormal peak pressures is integral to the healing process.[10] Extra-depth shoes with insoles and accommodative and functional devices can be used to decrease abnormal pressures.[12] Non-weight bearing using a wheelchair, crutches, or total contact cast is another offloading approach.[12]

As alternatives for ulcer closure, bioengineered tissues can also be used.[10] These living tissues stimulate wound healing and also deliver the growth factors to the site of ulceration. Dermoinductive grafts such as allografts and commercially available products contain living keratinocytes, which allow for the recruitment and activation of the wound bed tissues.[13] Dermoconductive grafts such as serve as scaffold matrices at the wound site allowing for wound closure.[14] Topical platelet-rich plasma and other blood products can also be used for wound healing.[15] Debridement, infection control, removal of bony prominences, and offloading are necessary preparations of the wound for the application of blood products and grafts.

Negative pressure wound therapy is a primary wound-closure method that can also be used to prepare the wound bed before other treatment modalities and is helpful for both acute and chronic ulcers.[10] It helps decrease the bacterial bio-burden and increases the granulation tissue and capillary budding at the base of the ulcer.[16] A combination therapy by applying a negative pressure wound therapy and a split-thickness skin graft is another option for wound closure.

Hyperbaric oxygen therapy is thought to be an effective treatment method in conjunction with local wound care, like offloading and debridement.[10] Hyperbaric oxygen therapy involves 100% pure oxygen inhaled inside an airtight chamber.[17] Targeting the underlying structural deformity and procedures like tendon-lengthening, exostectomy of bony prominence, or reconstruction are the surgical treatment options for non-healing ulcers. See Image. Jodhpur Technique.

Peripheral neuropathy contributes significantly to the development of ulcers, and proper wound care and management are vital for the treatment. Nitric oxide plays a crucial role in peripheral vasculo-neuropathies, and its induction is essential in ulcer management.[18] Using monochromatic near-infrared photo energy therapy can induce the release of nitric oxide, increasing blood flow to the local peripheral nerves. Topical nitric oxide can be used for painful peripheral neuropathies as well.[18] Supplements such as B6, B12, and folate are also used in managing peripheral neuropathies, and oral medications like tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs), selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), and antiarrhythmics can be used for symptomatic management of these conditions.

Differential Diagnosis

Foot ulcer differential diagnoses include malignancies like squamous cell carcinoma (SCC), basal cell carcinoma (BCC), melanoma, Kaposi sarcoma, lymphoproliferative malignancies, and primary skin disorders like sarcoidosis, necrobiosis lipoidica, bullous diseases, and pyoderma gangrenosum.[19]

Staging

Many classification systems have been developed to stage ulcerations for more efficient evaluation and treatment. The two leading classifications are the Wagner and Meggitt and the University of Texas ulcer classification systems.[20] The Wagner and Meggitt classification is based on the depth of the ulcer, while the University of Texas ulcer classification system is based on the depth in combination with the presence of ischemia and infection.[20]

In the Wagner and Meggitt classification, grade 0 has intact skin with a hyperkeratotic lesion or bony deformity. Grade 1 has a superficial necrotic or viable base ulcer with granulation tissue. Grade 2 extends to deeper structures like the bone, ligament, tendon, or deep fascia with no osteomyelitis or abscess. Grade 3 has osteomyelitis or deep abscess. Grade 4 has gangrenous forefoot changes, and grade 5 indicates a complete foot involvement with no healing.[20]

The University of Texas classification includes four grades (0-3) and four stages (A-D). Grade 0 stage A is a pre- or post-ulcerative lesion completely epithelialized (non-ischemic, non-infected), stage B indicates infection, stage C indicates ischemia, and stage D indicates both. Grade 1 stage A is a superficial wound without tendon, capsule, or bone involvement (non-ischemic, non-infected), stage B indicates infection, stage C indicates ischemia, and stage D indicates both. Grade 2 is a capsule- or tendon-penetrating wound (non-ischemic, non-infected); stage B indicates infection, stage C indicates ischemia, and stage D indicates both. Grade 3 is a bone- or joint-penetrating wound (non-ischemic, non-infected), stage B indicates infection, stage C indicates ischemia, and stage D indicates both.[20]

Prognosis

The prognosis depends on many variants, including the patient's comorbidities and utilized treatment modalities. The overall clinical outcomes of infected foot ulcers are poor, with a 17% lower limb amputation rate and a 15% death rate in one year.[21] Approximately 44% of the patient's ulcers heal within a year.[21] Healing is smoother in the absence of multiple or chronic foot ulcers and limb ischemia.[21] The ulceration prognosis can be improved by strictly adhering to the treatment plan and controlling the patient's cholesterol and glucose levels.

Complications

Foot ulceration in patients with diabetes is the leading cause of non-traumatic lower-limb amputations.[22] Approximately 35.4% of hospitalized patients with diabetes with foot ulcers undergo lower extremity amputation.[23] The common predictors of lower extremity amputation are ulcer duration, wound infection, Wagner grade 4 or higher, peripheral arterial disease, proteinuria, osteomyelitis, and leukocytosis.

Deterrence and Patient Education

Since most foot ulcer management is done as an outpatient, where the patient must continue a proper level of care outside of a clinical setting, patient education plays a crucial role in managing these patients' conditions. We should provide the patients with proper care, such as home nursing visits, to aid them in daily changes in dressing. The patient should be provided with educational materials on the importance of keeping the dressing dry, clean, and intact and ambulating with proper assistive devices such as a CAM walker, surgical shoe, crutches, and canes.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

An interprofessional team is required to manage patients with foot ulcers for successful healing. Diabetologists, diabetes nurses, orthopedists, vascular surgeons, general surgeons, orthopedic surgeons, interventional radiologists, podiatrists, orthotists, radiology coordinators, microbiologists, shoemakers, psychologists, nurse educators, and rehabilitation teams all work together to provide interdisciplinary foot care in foot specialized centers.[24] The team's full effort is warranted in the foot ulcer healing process. Different interdisciplinary management approaches have been developed to decrease the risk of foot ulcers.[25] All interprofessional team members must keep meticulous records of every patient encounter, record progress or lack thereof, and contact other team members as appropriate to ensure optimal patient care, leading to the best possible outcomes. [Level 5]