Continuing Education Activity

Epithelioid sarcoma is a rare soft tissue sarcoma of young adults that presents as a painless, slow growing mass. Complete surgical resection can be curative, however recurrence and late metastasis can occur. This activity covers the diagnosis and management principles of epithelioid sarcoma and highlights the role of an interprofessional approach to care for patients with this condition.

Objectives:

Describe the classic presentation of epithelioid sarcoma.

Identify the etiology of epithelioid sarcoma.

Describe the treatment strategy for patients with epithelioid sarcoma.

Summarize the importance of collaboration and coordination among the interprofessional team to enhance management of epithelioid sarcoma.

Introduction

Epithelioid sarcoma was first described by Enzinger in 1970 as a rare soft tissue sarcoma that mimics granulomatous disease, carcinoma, and synovial sarcoma.[1] The tumor typically presents as a painless, slow-growing soft tissue swelling in the distal extremity of young adult males. It is locally invasive and frequently metastasizes to regional lymph nodes and distant sites, most commonly to the lungs. Complete surgical resection is curative in low-stage disease; however, a risk of recurrence and late metastasis remains.[2] Epithelioid sarcomas are tumors of purportedly mesenchymal origin that show ultrastructural and immunophenotypic evidence of epithelial differentiation.[3] The mixed differentiation of epithelioid sarcoma can make the differential diagnosis challenging from a histopathologic perspective. The differential diagnosis is narrowed by the somewhat unique epithelioid sarcoma immunophenotype expressing cytokeratin, epithelial membrane antigen, and CD34. Epithelioid sarcoma is one of only a few tumors that characteristically lacks INI-1/SMARCB1 expression.

Etiology

Epithelioid sarcomas are malignant tumors with mixed differentiation toward both mesenchymal and epithelial cell types. Up to 90% of epithelioid sarcomas show loss of integrase interactor-1 (INI-1) expression.[4] INI-1 is part of the SWI/SNF chromatin remodeling complex expressed in all normal nucleated cells. This chromatin remodeling complex is essential to biological function by altering nucleosomes to allow for transcription of DNA. INI-1, also commonly known as SMARCB1, is on chromosome 22 at the 22q11 band. A spectrum of gene deletions and rearrangements including translocation events involving the 22q11 locus are putatively responsible for tumorigenesis in INI-1 deficient epithelioid sarcomas.[5] Intriguingly, an association with prior trauma at the site of the tumor has been noted in up to 27% of occurrences.[3] Prior trauma to the distal extremity, however, is logically an all too common of an occurrence for further speculation as to an inciting event.

Epidemiology

Epithelioid sarcomas are rare, representing less than 1% of soft tissue sarcomas,[2] and have a predilection for men (up to 2:1 male to female ratio).[6] Most reported tumors occur in young males ranging in age from 10 to 45 years.[2][3][1][7] The extremes of ages include ages 4 to 90, with a median age of 27 years.[6]

Pathophysiology

Epithelioid sarcomas have no definitive cell of origin but are considered to be true mesenchymal cells that show epithelial differentiation. This is based on ultrastructural studies that show the malignant cells to resemble mesenchymal cells closely, often with myofibroblastic characteristics.[3][7] The proximal-type variant of epithelioid sarcoma, which often microscopically has rhabdoid morphology, ultrastructurally shows perinuclear whorls of intermediate filaments consistent with at least some degree of rhabdomyocyte differentiation.[7] The immunohistochemical staining profile, discussed in more detail below, also supports bi-differentiation toward mesenchymal and epithelial lines. The tumor has a unique immunophenotype, showing strong expression of the epithelial markers cytokeratin and epithelial membrane antigen (EMA) as well as positive labeling with the mesenchymal markers CD34 and vimentin.

Histopathology

Epithelioid sarcoma was first described by Enzinger in 1970 as a challenging sarcoma diagnosis because it closely mimics granulomatous diseases and has features of benign and malignant epithelial neoplasms.[1] It is likely that some epithelioid sarcomas were misdiagnosed before Enzinger’s description due to the histologic mimicry of the tumor.

Microscopically, the conventional or usual type of epithelioid sarcoma has a nodular or lobular architecture with central areas of necrosis. Epithelioid cells (polygonal with relatively abundant cytoplasm) with eosinophilic cytoplasm surround the necrosis, imparting a necrotizing granulomatous pattern to the low-power diagnosis. The nuclei are generally not too atypical, and mitotic figures are conspicuously present.[1][3] Tumor cells at the periphery often take on a spindled or sarcomatous appearance. Various histologic patterns further complicate the histologic diagnosis as some tumors take on a more angiomatoid or fibromatoid appearance.[6][8][6] These features can lead the pathologist toward vascular neoplasms and more benign processes like fibromatosis, or even reactive lesions such as nodular fasciitis.

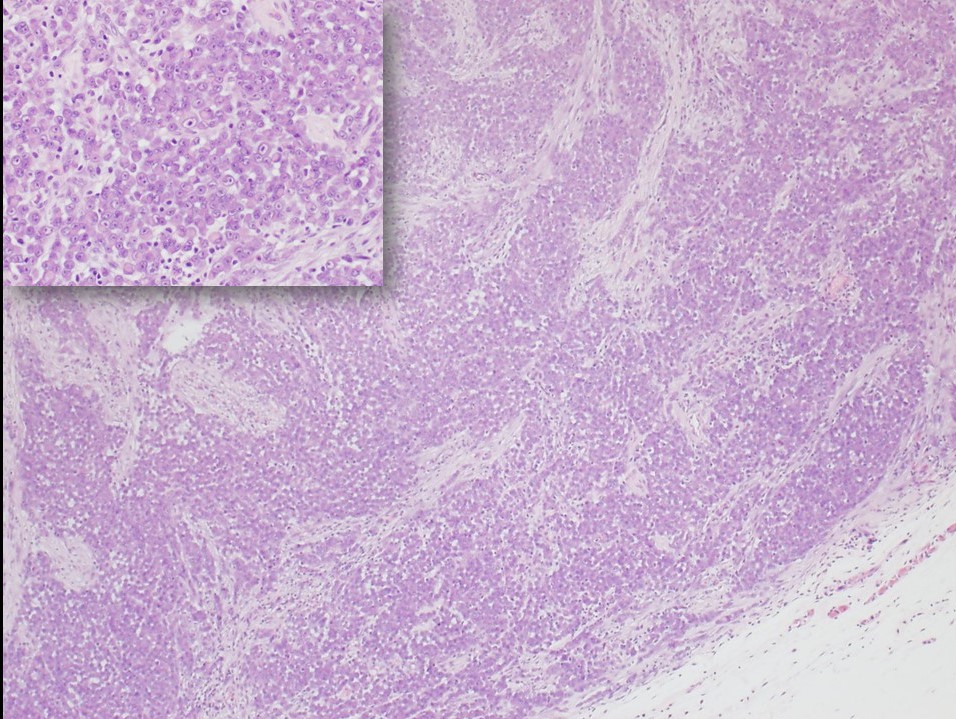

The proximal-type variant of epithelioid sarcoma lacks the granulomatous pattern of necrosis. The tumor consists of cellular nodules with more cytologic pleomorphism, nuclear atypia, and even signet-ring-like vacuolation.[3][7] Rhabdoid morphology with prominent nucleoli is characteristic of this lesion (see Figure 1). Although the proximal type is characteristically found near the trunk, it is defined by its histologic features and not its location.[2][9] Furthermore, the often proximal location of this variant leads to more diagnostic difficulty because of the overlapping features with metastatic carcinoma that would be more common to occur at proximal sites such as the groin and pelvic area.[7]

The immunohistochemical profile of epithelioid sarcoma is relatively unique as it strongly expresses cytokeratins, EMA, vimentin, and is often CD34 positive. The most diagnostically useful finding is lack of INI-1 expression in tumor cells. Also helpful in the differential diagnosis, expanded upon in the differential diagnosis section below, is the typically negative immunolabeling of the tumor cells for S100, desmin, and CD31.[3][4][6][10]

Immunohistochemical Profile Summary[3][4][6][10]

Positive Labeling

- Cytokeratin

- Epithelial membrane antigen

- Vimentin

- CD 34 (approximately 50% of cases)

Negative Labeling

- INI-1/SMARCB1

- S100

- Desmin

- Factor VIII-related antigen

- Cytokeratin 7

History and Physical

Epithelioid sarcoma most often presents as a distal upper-extremity multinodular swelling that is slow-growing, painless, and sometimes ulcerates.[2][3][6] The lesion can be centered in the dermis, subcutis, or deep fascia. It characteristically invades along fascial planes and tracks along tendons and aponeuroses.[2] A proximal variant of epithelioid sarcoma exists that tends to occur more often in the perineal, pubic, genital and truncal regions; although it is defined by its histologic features rather than its location.[2][7]

Masses can be large, up to 20 cm, especially in the proximal variant, but are often less than 5 centimeters in greatest dimension.[1][3][6] Epithelioid sarcoma aggressively invades locally and has a propensity for regional lymph node metastasis. Distant metastatic spread, especially to the lungs and scalp, has been well documented.[2] The clinical behavior of the tumor has probably best been described by Chase and Enzinger as an “indolent, relentless clinical course” due to the aggressive nature of local recurrences and metastatic potential.[6]

Evaluation

Patients present with a mass or swelling but are otherwise typically without significant signs or symptoms of a malignant disease process. Initial workup for a mass that is concerning clinically for epithelioid sarcoma should be biopsied for definitive pathologic diagnosis. Physical examination of the patient should include a meticulous lymph node examination, as regional lymph node metastases are common.[2] A thorough review of systems to include respiratory symptoms is prudent to assess for lung involvement, the most common site of distant metastases.

Treatment / Management

After definitive tissue-based diagnosis, treatment depends on the presence or absence of metastatic disease. Metastatic disease should be ruled out based on a thorough clinical and radiological examination, particularly focused on regional lymph nodes and pulmonary examination. Ultrasound scanning of regional lymph nodes and sentinel lymph node biopsy is recommended to improve metastatic workup accuracy.[2]

Surgical resection of primary tumors with no metastases can achieve a cure if the primary tumor is amenable to complete resection with no residual tumor.[3][6] Radiation therapy (RT) is often added to mitigate local recurrence; however, the use of RT is relatively undefined.[11] Surgery with curative intent still carries a risk of recurrence and late discovery of metastases. Inoperable tumors, incomplete resections, and metastatic disease can be offered palliative measures such as RT.[2][11]

Differential Diagnosis

The diagnosis of epithelioid sarcoma is challenging because of its dual mesenchymal and epithelial differentiation. This differentiation allows the tumor to masquerade histologically as various other reactive, benign, and malignant processes. The immunohistochemical labeling can confirm the diagnosis although a plethora of other more common diagnostic entities that have histologic and immunophenotypic overlap must be considered. The histopathologic diagnosis can best be rendered in the appropriate clinical context (typically a soft tissue mass on the extremity of a young male) and supported with immunohistochemical staining.

The differential diagnosis based on histomorphology generally includes reactive and benign lesions such as granulomatous diseases, nodular fasciitis, fibrohistiocytic lesions, fibromatosis, and tenosynovial giant cell tumors. Malignant lesions in the differential diagnosis include metastatic carcinoma, melanoma, synovial sarcoma, vascular neoplasms, spindled squamous cell carcinoma, malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor (MPNST) and extrarenal rhabdoid tumor.[1][3][4][6]

Complete lack of INI-1 expression is characteristic of up to 90% of these tumors.[4] Other tumors that characteristically show complete lack of INI-1 expression in all cases are renal medullary carcinoma and extrarenal rhabdoid tumors. Tumors such as epithelioid MPNST, pediatric myoepithelial carcinomas, and extraskeletal myxoid chondrosarcomas also lack INI-1 expression in some instances.[12]

A summary of helpful immunohistochemical stains is provided for epithelioid sarcoma (ES):

- CD34 positive in half of ES (negative in synovial sarcoma and most carcinomas)

- Vimentin-positive in ES (negative in many carcinomas, except notably endometrial and renal)

- INI-1, complete loss is distinctive as described above in this section

- CK7 negative in ES (positive in synovial sarcoma)

- CK5/6 and p63 negative in ES (positive in squamous cell carcinoma)

- S100 negative in ES (positive in MPNST and many melanomas)

- CD31 negative in ES, except one documented case (positive in vascular lesions)[13]

- SALL4 negative in 89% of ES (positive in 71% of malignant rhabdoid tumors)[14]

- ERG variably positive in ES (negative in all malignant rhabdoid tumors)[14]

- Of note, vascular markers ERG, FLI1, and D240 have been demonstrated in ES[8][10]

Prognosis

Prognosis, as with most malignancies, is primarily determined by the clinical stage of the disease. Epithelioid sarcoma prognosis is most closely associated with tumor size, vascular invasion, resectability, and metastases.[6] Large tumor size and early metastases are independently associated with poor outcomes.[9] The proximal type is generally described as a more aggressive tumor; however, at least one study[2] demonstrated no significant difference in overall survival between the proximal and usual types of epithelioid sarcoma.

Gender, age of diagnosis, site, tumor size, and microscopic findings affect prognosis. Female patients have better outcomes. Distal lesions have been shown to have better outcomes compared to proximal. Presentation at an earlier age has better outcomes. Tumors more than 2 cm in diameter have been correlated with worse outcomes, as do tumors with necrosis and vascular invasion. Mitotic index is a prognostic factor.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Epithelioid sarcoma presents in young patients as a slow-growing mass of the extremity. The deceptively benign nature of the clinical presentation requires a high-index of suspicion by the astute primary care provider for a neoplasm that requires biopsy. Upon diagnosis, the healthcare team requires an interprofessional approach to address the appropriate staging, treatment, and long-term management of the disease. This will involve radiology, surgery, pathology, and nursing. Curative outcomes can be achieved after complete resection, but there is a high risk of local recurrence that can be mitigated with radiation therapy, particularly in tumors greater than 3 cm.[15] (Level II) In non-resectable cases and metastatic disease, palliative treatment coordinated with medical oncology and radiation oncology has remained mostly undefined.[11] (Level V)