Continuing Education Activity

Rhombic flaps are highly versatile flaps based on their unique mechanical characteristics with a wide range of potential applications. This activity reviews rhombic flaps and their role in reconstructive surgery. It will highlight key practical considerations required for the surgical procedure and perioperative care within the extended healthcare team.

Objectives:

- Describe common indications/applications of the rhombic flaps in reconstructive surgery.

- Outline the preparation and technique required for rhombic flap reconstruction.

- Review the potential complications of rhombic flaps reconstruction.

- Identify strategies to improve collaboration between the interprofessional care team to advance rhombic flap reconstruction and improve patient outcomes.

Introduction

Rhombic flaps are geometric local transposition flaps and offer significant versatility within reconstructive surgery. This flap is most commonly used to fill skin cancer defects of the head and neck region. While successful outcomes have been reported in a range of anatomical locations and pathological defects such as in spina bifida, burn contractures, chronic pilonidal sinuses, hand, and breast reconstruction.[1][2][3] This flap takes advantage of skin laxity adjacent to the defect to allow the transposition of tissue with similar characteristics to the tissue excised. This can allow a superior cosmesis when compared with skin graft reconstruction.[4]

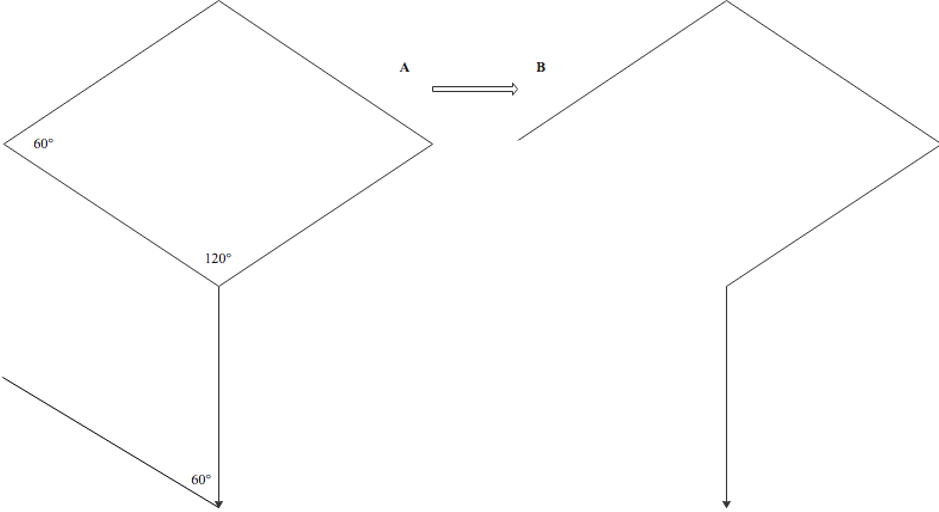

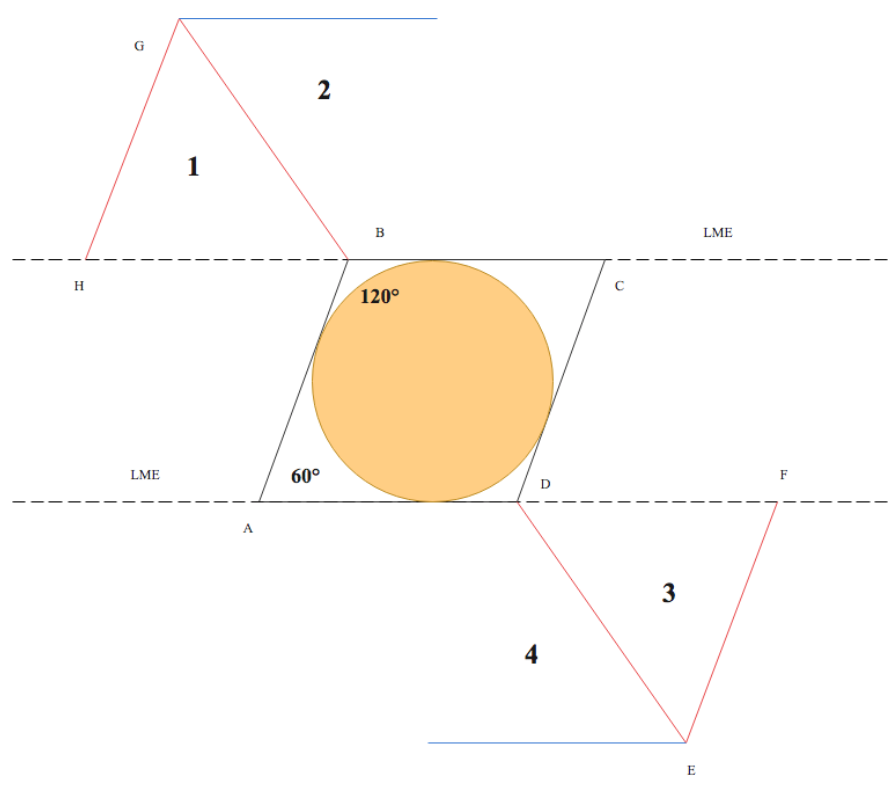

The term ‘rhombus’ is derived from Euclidian geometry, describing a quadrilateral shape with opposing equal acute and obtuse angles, while the term ‘rhomboid’ denotes a parallelogram. The term ‘rhombic’ is, therefore, most accurately used to describe flaps resembling a rhombus, while ‘rhomboid’ for those resembling a rhomboid or parallelogram. The rhombic flap was first described by the Russian surgeon Alexander Limberg in 1945 and published in English in 1966.[5] The flap was defined by a characteristic quadrilateral rhombus shape, allowing transposition into skin defects designed with a corresponding shape. (Figure 1)

Common Rhombic Flap Variations

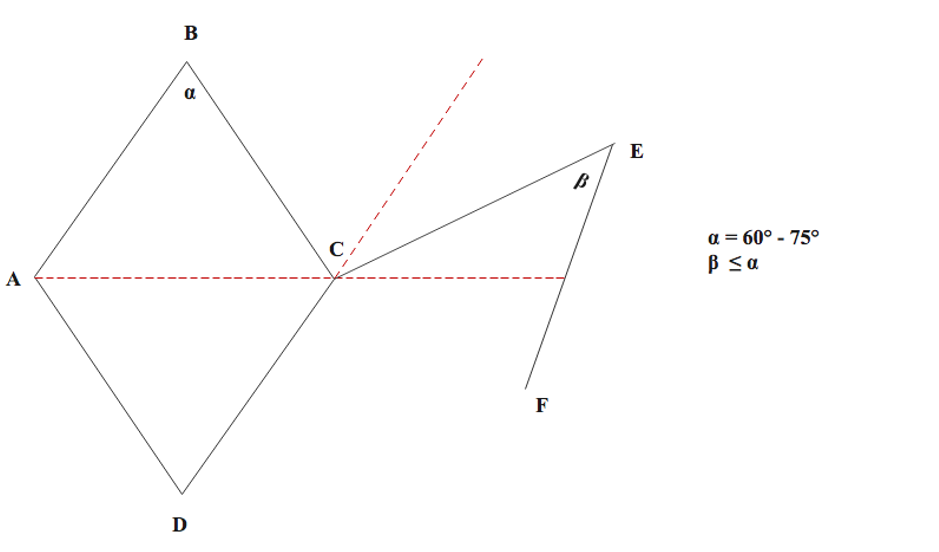

Claude Dufourmental modified Limberg rhombic flap design in 1962, describing closure of defects with a more acute flap angle allowing greater flexibility and ease of closure.[6] Firstly, when designing the defect (Figure 2), the acute angle (alpha) may have a range of 60-75 degrees. The flap itself is designed by aligning the first incision (CE) as the bisection of the angle between the line of the short diagonal axis of the rhombus defect (AC) and the line of its adjacent side (DC). The flap angle (beta) may equal to defect angle (alpha) or decreased if necessary, allowing further flexibility. Advocates claim superiority over the Limberg flap in terms of improved blood supply and ease of donor site closure through the use of a wider pedicle width and more flexible design.[2][6][7] The adaptability for surgical resection and reconstruction has been reported to be superior to Limberg flap by Sebastian et al. in the context of chronic pilonidal disease.[8]

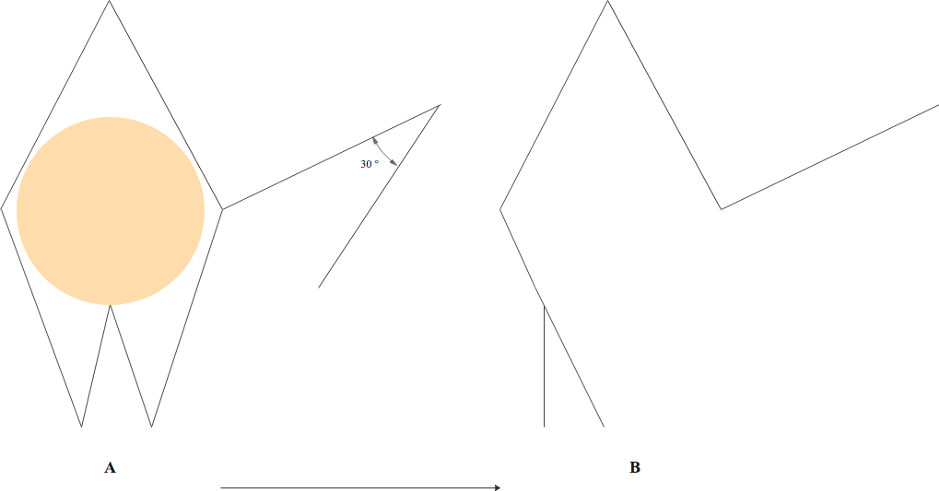

Webster further modified the design in 1978 by combining an acute 30-degree flap angle with an M-plasty to close the defect base. (Figure 3) The underlying principals stipulate that the narrower 30-degree flap angle functions to reduce donor site closure tension, and the use of an M-plasty means the rotation arc is shared between two 30-degree angles with improved distribution of tension and reduced distortion of the tissue. In the original case series, Webster et al. reported favorable outcomes in terms of reduced scar widening and reduced areas of skin excess, supposedly due to a more balanced distribution of tension.[9]

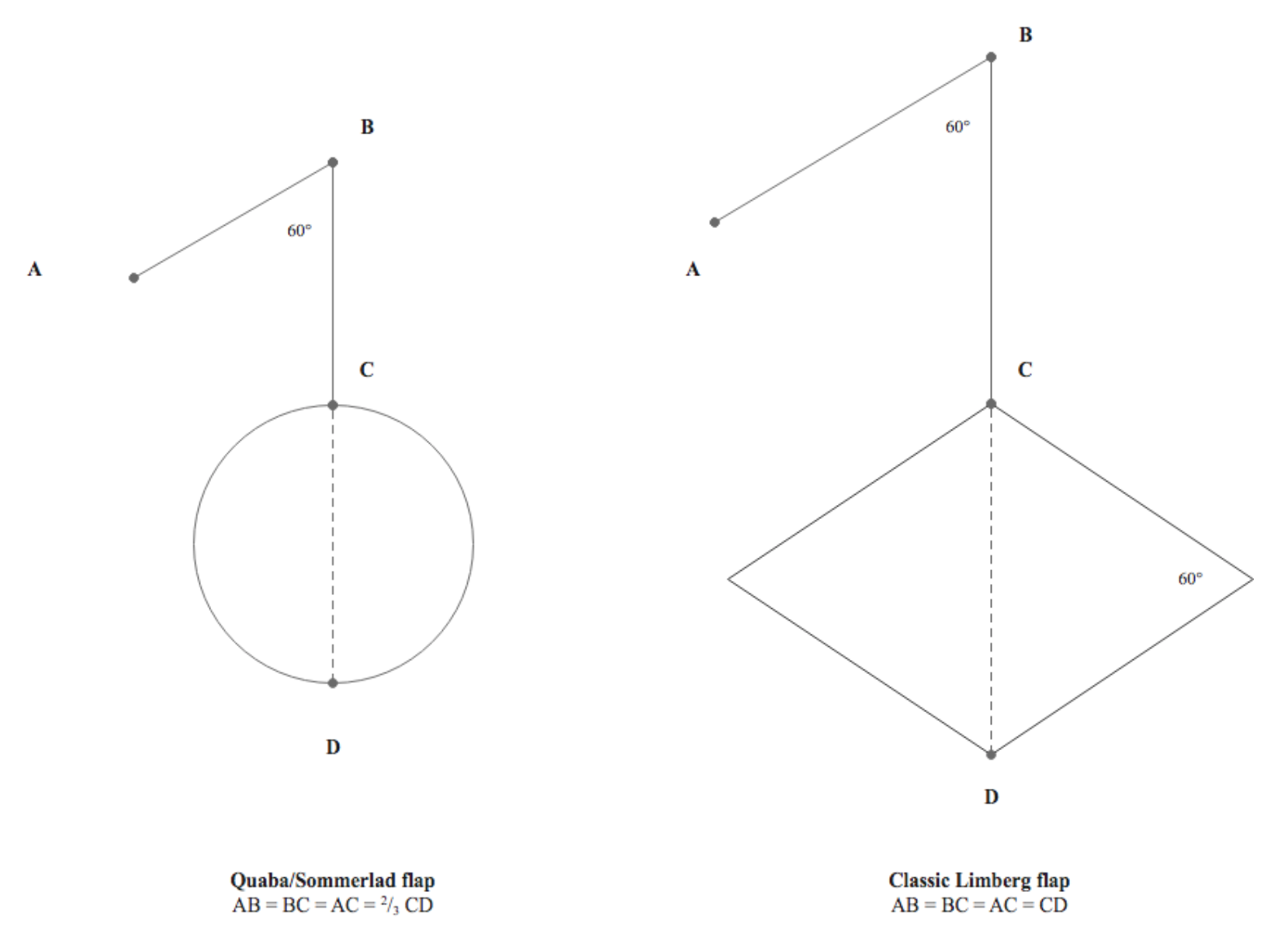

In 1987, Quaba and Sommerlad proposed a rhombic flap modification: reconstructing a round defect with a rhomboid flap. This design (Figure 4) involved reconstructing a round defect with a rhomboid flap with sides two-thirds the diameter of the defect, but with an equivalent 60-degree flap angle to Limberg design. The authors reported a case series of 175 patients with head and neck skin defects reconstructed with ‘Quaba/Sommerlad’ flaps. The stated advantages over the classic design included flexibility in flap transposition and donor site orientation, as well as no requirement for healthy tissue to be sacrificed in creating a rhombic shaped defect.[10]

Multiflap variants involving two, three, and four rhombic flaps have been described by Lister and Gibson, Jervis, and Turan et al., respectively.[11][12][13] These have been applied to reconstruct larger defects and areas with reduced pliability of adjacent skin. El-Tawil et al. reported a case series of 8 patients with pilonidal sinus disease reconstructed with double rhomboid flap, with reported low recurrence and complications rate, as well as precluding the need for complex reconstruction. While the reconstruction of meningomyelocele defects with triple rhomboid flaps in a case series of 7 patients, and quadruple rhomboid flaps in a single patient case report, have both described good patient outcomes.[14][13][14]

Although a wide range of different designs has been proposed with application to various anatomic sites, this article will focus on the most widely reported Limberg flap method applied to the reconstruction of head and neck skin defects.

Anatomy and Physiology

The rhombic flap is a random-pattern local flap that relies on blood supply through the subdermal plexus. Anatomically this plexus is located at the junction between the reticular dermis and the subcutaneous layer. From this plexus, arterioles pass superiorly to supply the dermis and epidermis via the dermal and subepidermal plexuses.[15] The rich anastomotic blood supply of the subdermal plexus provides the basis of circulation to random pattern flaps, without a requirement for the axiality of blood supply to be considered. When raising the flap within the subcutaneous plane, the inclusion of a cuff of subcutaneous fat as an absolute minimum helps preserve the subdermal plexus. While maintaining rhombic flap proportions on the horizontal plane, the use of minimal undermining of the pedicle also ensures adequate blood supply and reduces the risk of partial or complete flap necrosis.[16]

To successfully transpose and advance the flap from an area of relative skin laxity, careful orientation is advised. This involves awareness of the lines of maximal extensibility (LMEs) and the relaxed skin tension lines (RSTLs) or Langer lines. The rhombic flap should be orientated so that the short diagonal axis of the flap is perpendicular to the RTSLs.[7][17]

Particularly in the head and neck region - attention to preserving divisions between aesthetic subunits is important for cosmesis. Placement of incisions in existing creases and in borders between subunits functions to leave the least conspicuous scar.[18] Furthermore, adjacent facial landmark structures should be considered when distributing tension to avoid distortion, for example, when preventing an ectropion in the infraorbital region.[17]

Indications

Small to medium-sized defects which cannot be primarily closed may be reconstructed with rhombic flaps. This flap offers advantages over skin grafting, such as improved color and texture matching and fewer wound sites. It may be applied to a variety of anatomic regions, particularly facial defects such as those involving the cheek, eyelids, chin, temple, and nose.[18] This adaptability to different reconstructive defects utilizes adjacent skin laxity to facilitate vector transposition of the flap.

Contraindications

In the context of skin cancer surgery, inadequate oncological clearance may be considered an absolute contraindication to flap reconstruction. Therefore, in some situations, reconstruction may be delayed until clearance or until Mohs micrographic surgery can be performed.

Relative contraindications may include patient factors such as heavy smoking, poorly controlled diabetes, anticoagulants, or reduced perfusion, for which complications may be higher.

These are generally modifiable, for example, through smoking cessation, suspension of coagulant medication, and optimized glycaemic control. Some anatomic regions should be avoided, such as those with poor adjacent skin laxity or proximity to landmarks prone to disruption by tension.

Equipment

Preparation

- Surgical site marker

- Local anesthetic such as lidocaine 1% with 1:200,000 adrenaline with syringe and needles.

- Antiseptic solution such as 1% chlorhexidine solution or povidone-iodine

- Surgical drapes

Intraoperative

- Scalpel (15 blade)

- Forceps

- Dissecting scissors such as tenotomy scissors

- Suture scissors

- Skin hooks

- Bipolar electrocautery

- Normal saline solution for washout

- Sutures size and type depending on anatomical location (e.g. absorbable for deep dermal and non-absorbable for simple interrupted)

Post-operative

- Steristrips

- Surgical dressing tape

- Additional dressings if indicated

Personnel

This procedure is usually performed by plastic surgeons, maxillofacial surgeons, dermatologists, or otorhinolaryngologists, although additional suitably qualified physicians or surgeons may be proceduralists depending on local practice. A scrub team and circulating operating room team members are instrumental in assisting with the surgery.

Preparation

Informed consent with a full explanation of the procedure, aftercare, intended benefits, and risks of complications, as well as a discussion of the alternative management options should be undertaken. Sufficient time for the patient to consider the information should be provided. before signing a consent form. Preoperative clinical photographs are recommended for patient record purposes.

Rhombic flaps are most commonly used in facial defects under local anesthetic, as described for the procedure in this article. Larger defects or those complicated with patient factors may require general anesthetic or sedation to complete the procedure and may require a preoperative anesthetic work up.

Technique or Treatment

Surgical markings to design the flap should be undertaken as a first step. For the Limberg flap, this involves designing the defect as a rhombus with opposing 120-degree and 60-degree angles, ensuring adequate resection margins according to the relevant guidelines. The short axis of the defect exists between the 2 opposing 120-degree angles, with the first limb of the flap incision being a continuation of the short axis with an equal length to the sides of the defect. The second limb is then drawn parallel to the sides of the defect, at a 60-degree angle from the first limb.[16]

The orientation should be determined by ensuring that the short axis of the flap is parallel to the LMEs and perpendicular to the RSLTs to facilitate transposition through inherent skin laxity. (Figure 5) The RSLTs or Langer lines may be identified by existing skin creases or wrinkles, although a pinch test may be performed if there is uncertainty. For the short axis of the flap, to be parallel to the LMEs, two clinical flap options exist. This is as opposed to the four geometrically possible that can be designed. (Figure 5) The final option also depends on proximity to neighboring landmarks and the aesthetic subunits. This should be drawn out with a surgical marker.

Local anesthetic infiltration should be undertaken to encompass the surgical field. Following this, the surgical field should be cleaned and draped before commencing the procedure.

If the defect is assumed to be excised with confirmed clearance, the defect should be extended to form a rhombus shape defect through additional excision of tissue. The flap should then be elevated in the same plane as the defect, typically the subcutaneous plane, with sufficient depth to include the subdermal plexus. Firstly, the two limbs of the flap are incised, and then the flap is raised by dissection of the tissue plane using dissecting scissors or a scalpel blade. This process may be aided by an assistant providing traction using skin hooks. Following flap harvest, thorough hemostasis with diathermy is advised to ensure a dry wound bed and thus reduce the risk of hematoma formation.

After elevation of the flap, it may be transposed into the defect. The donor site should be closed first with a robust suture technique such as two-layer deep dermal and interrupted sutures. This closure involves the most tension, with the maximum point being at the apex. Some undermining of the adjacent tissue may be required, although this should be minimized to prevent disruption of blood supply.[19] The flap is then secured into the defect, with the corner sutures placed first to ensure correct alignment. The flap edges may then be fully closed using a two-layer closure technique. Finally, clinical confirmation of flap perfusion should be performed, before cleaning and dressing of the surgical wound.

Complications

Complications of rhombic flap reconstruction should be fully explained during the consent process and may be divided into general and specific complications.

General complications include pain, bleeding, infection, wound breakdown, scarring (including abnormal).

Specific complications of partial or complete flap failure are uncommon and may be caused by surgical factors such as over thinning and undermining of the flap. These may be influenced by patient factors such as smoking.[18] Additionally, the distribution of tension and lymphatic drainage may result in aesthetically significant bulges or dog-ear, as well as ‘pin-cushion’ deformities and tethering of adjacent structures.[16] There is also a risk of damage to underlying structures specific to the anatomic region involved. The significance of the underlying structures should be fully explained. For example, if one is operating within the temporal region, potential disruption to the motor function of the temporal branch of the facial nerve should be explained.

Clinical Significance

Rhombic flaps are highly versatile flaps which may be used to reconstruct a variety of defects. Favorable cosmetic and functional outcomes may be obtained when fundamental anatomical and mechanical principals are applied.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Successful patient outcomes are reliant on well-orchestrated interprofessional team care. Although the surgery is primarily performed by surgeons or dermatologists, they form only part of the extended healthcare team. The involvement of specialist nurses within preoperative, intraoperative (scrub) and post-operative wound dressing environment are fundamental to the patient pathway. While other allied health professionals including physician associates, operating room circulating team members, pathologists, and pharmacists play important roles. Early identification of flap complications through patient education and by nursing staff with appropriate escalation is vital to patient outcomes.[20] [Level 5] In the context of skin cancer, the specialist multidisciplinary team of pathologists, radiologists, surgeons, and dermatologists are crucial to confirm adequate oncological clearance. They also co-ordinate on-going surveillance and care.