Continuing Education Activity

Pulmonary eosinophilia (PE) is defined as the infiltration of eosinophils into the lung compartments constituting airways, interstitium, and alveoli. Various infections, drugs, parasites, autoimmune processes, malignancies, and obstructive lung diseases have been associated with increased eosinophils in the lungs. This activity reviews the cause and pathophysiology of pulmonary eosinophilia and highlights the role of the interprofessional team in its management.

Objectives:

- Identify the etiology of pulmonary eosinophilia.

- Review the workup of a patient with pulmonary eosinophilia.

- Outline the treatment and management options available for pulmonary eosinophilia.

- Summarize the importance of improving care coordination among interprofessional team members to improve outcomes for patients affected by pulmonary eosinophilia.

Introduction

Pulmonary eosinophilia (PE) is defined as the infiltration of eosinophils into the lung compartments constituting airways, interstitium, and alveoli. Various infections, drugs, parasites, autoimmune processes, malignancies, and obstructive lung diseases have been associated with increased eosinophils in the lungs.[1][2][3]

Etiology

The finding of pulmonary eosinophilia is not specific to a certain disease. However, it breaks the differential down into a handful of diseases that the physician can narrow their differential towards. Pulmonary eosinophilia may be broadly categorized into primary/idiopathic and secondary/extrinsic from external factors.[4][5][6][7]

Primary pulmonary eosinophilia occurs due to unknown causes, such as acute eosinophilic pneumonia (AEP), chronic eosinophilic pneumonia (CEP), eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis (EGPA), and hypereosinophilic syndrome (HES). Secondary pulmonary eosinophilia occurs due to known causes, such as allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis (ABPA), parasites, medications, radiation effects, and malignancies.

Mildly increased levels of eosinophils may be found in the bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) differential cell count in the idiopathic interstitial pneumonia, sarcoidosis, and Langerhans cell histiocytosis; however, in these diseases, they are just a mere association and have no causal effects.

All drugs taken in the weeks or months preceding the syndrome of eosinophilic pneumonia (EP) must be thoroughly investigated, including illicit drugs. Medications that are commonly known to cause drug-induced EP include nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, antibiotics such as trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, penicillin, nitrofurantoin, minocycline, angiotensin-converting enzyme-inhibitors, sulfa drugs, and ethambutol.

Parasitic infestation is the most common cause of EP worldwide. Simple pulmonary eosinophilia, also termed Loeffler syndrome, refers to the acute, transient pulmonary radiographic opacities and peripheral blood eosinophilia associated with intestinal parasites, commonly described with Ascariasis and Strongyloidiasis.

Epidemiology

The true incidence of AEP is not known, as much of the world literature derives from case reports and case series, which imply a very rare incidence. However, it is much more common in men. CEP is also a rare disease, forming less than 2.5% of ILD cases reported. It is more common in women, who are affected twice as much as men with the majority of them, being non-smokers. The incidence of EGPA is also not known among the ANCA-associated vasculitis; however, it is the least common.

Pathophysiology

Eosinophils are one of the main cells of allergic inflammation. They develop from hematopoietic stem cells and undergo maturation and activation by the IL-5 secreted by TH-2 lymphocytes. IL-3 and granulocyte macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) are also involved in the eosinophil maturational pathway.

EP is characterized by the prominent infiltration of the lung parenchyma by eosinophils, along with other inflammatory cells such as lymphocytes, plasma cells, and polymorphonuclear neutrophils. Macrophages and scattered multinucleated giant cells may be present in the infiltrate and may contain eosinophilic granules or Charcot–Leyden crystals. Activated eosinophils release pro-inflammatory cytokines, reactive oxygen species, and cationic proteins, such as major basic protein and eosinophil cationic protein, which lead to tissue pathology. The release of platelet-activating factor and leukotrienes contributes to bronchospasm. Local tissue injury due to these mediators causes respiratory tract damage and can lead to respiratory failure. The distribution of EP depends on the underlying etiology; it can be diffuse or focal.

In EP due to Ascaris, the transmission is through the fecal-oral route. In Strongyloidiasis, the entry is through the skin. They both settle in the intestine and release eggs, which form larvae that penetrate into the venous circulation to the lungs. In the lungs, they migrate through the bronchi and trachea and are swallowed into the small intestine again. The pulmonary symptoms mainly occur during the migration in the lungs.

ABPA results from colonization of Aspergillus forming mucus plugs in the bronchi with an inflammatory response.

Histopathology

The findings of pathology vary based on the etiology. However, the central theme is findings of eosinophil infiltration in the lung parenchyma.

The pathological features described in chronic eosinophilic pneumonia may be considered the common pathologic finding of eosinophilic pneumonia, in which there are foci of organizing pneumonia in a background of alveolar and interstitial eosinophil infiltration. Acute eosinophilic pneumonia typically shows acute and organizing diffuse alveolar damage with interstitial and alveolar infiltration by eosinophils.

Eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis (EGPA) on biopsy shows necrotizing granulomatous inflammation often involving the respiratory tract and a necrotizing vasculitis predominantly affecting small to medium vessels.

History and Physical

The evaluation of EP should include a careful history of asthma, occupational or environmental exposures, travel, medications, infectious symptoms, the presence of systemic findings, and the acuity or chronicity of symptoms. Based on certain signs and symptoms, it can help narrow down the differential further. Findings of a rash can point towards EGPA, HES, drug-induced, or parasitic causes. Findings of cardiomyopathy could be due to system involvement of EGPA or HES. Upper airway involvement could be due to EGPA or ABPA.

Acute eosinophilic pneumonia (AEP) usually is acute onset within days to weeks of symptoms with dyspnea, cough, and fever. No other causes of eosinophilic pneumonia can be elicited from history such as inciting drugs. AEP occurs predominantly in males, and they have no prior history of asthma. Cigarette smoking is believed to have a causative role in this disease as the majority of the cases reported have either recently started smoking or have had an alteration in their smoking habits. Findings on examination are tachypnea, tachycardia, crackles, and wheezing; many have acute respiratory failure, with around 70% of the patients needing mechanical ventilation.

Chronic eosinophilic pneumonia (CEP) occurs predominantly in women and nonsmokers. Though the etiology is not known, it is more frequently seen in asthmatics and those with a history of atopic disease. Usually, it presents with a few months of dyspnea, cough, or chest pain and may have associated constitutional symptoms.

Eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis (EGPA) presents at a mean age of 35, with a history of severe corticosteroid-dependent asthma that usually precedes the onset by a few years. Up to 75% of patients have associated rhinitis and sinusitis. These patients have multisystem vasculitis and can have constitutional symptoms, arthralgias/myalgias, signs and symptoms of heart failure, renal failure, neuropathy, and palpable purpura.

In HES, symptoms are nonspecific such as a cough and dyspnea, which are seen in only one-quarter to one-half of all cases. They often will present with signs and symptoms of heart failure, central nervous system complaints, peripheral neuropathies, and cutaneous changes such as urticaria and angioedema.

Patients with ABPA usually have a history of poorly controlled asthma or cystic fibrosis with a productive cough, occasionally with brownish sputum and wheezing.

Loeffler syndrome occurs in temperate and tropical climates. Pulmonary symptoms are usually coughing and wheezing with fever. The symptoms may remit spontaneously. Tropical eosinophilia commonly occurs in young male adults living in a tropical climate of Asia or Africa. Patients usually have a dry cough which is worse at night and associated with wheezing.

Evaluation

A chest x-ray would be needed as part of the initial evaluation to assess for infiltrates and also compare to prior films to check for transient or changing infiltrates with time. Laboratory tests for complete blood count with differential, and anti-nuclear cytoplasmic antibodies (ANCAs), other serologic studies, and stool for ova and parasites should be obtained.

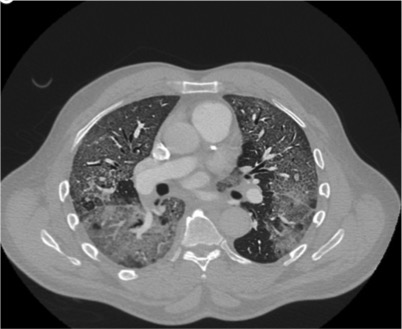

Pulmonary function testing can be done to evaluate for evidence of obstructive or restrictive lung disease that could occur depending on the underlying EP. CT chest without contrast may be done to further evaluate the lung parenchyma and to look for bronchiectasis.[8][9][10]

The diagnosis of PE can be made in three different settings:

- Peripheral eosinophilia with lung opacities.

- Elevated BAL eosinophil count greater than 25%.

- Lung tissue eosinophilia on biopsy.

Any one of the above findings can be used to diagnose PE. The peripheral eosinophil count can be normal in PE. Bronchoscopy with BAL is a common diagnostic tool that identifies the pulmonary eosinophilia with BAL fluid eosinophil greater than 25%. Normally, eosinophils constitute less than 2% of the BAL cell count. Peripheral eosinophilia occurs when eosinophil blood count is greater than 0.5 × 10/L (500/microliters). However, to diagnose eosinophilic pneumonia on the sole finding of blood eosinophilia and pulmonary opacities requires markedly elevated eosinophilia (greater than 1 × 10 /L) together with typical clinical-radiologic features.

Bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) has become a widely accepted noninvasive surrogate of a lung biopsy for the diagnosis of eosinophilic pneumonia. Surgical biopsy or video-assisted lung thoracoscopy is rarely required to make a diagnosis of eosinophilic pneumonia. However, it may be useful at times when the underlying etiology causing eosinophilic pneumonia needs to be determined or when the diagnosis is unclear based on BAL only. Once a diagnosis of pulmonary eosinophilia is established, clues from the history, physical, and investigations should guide the clinician towards further investigations and a diagnosis of the underlying etiology.

In patients with poorly controlled asthma, the workup would be guided towards allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis (ABPA). Other differentials to consider would be EGPA and CEP. Testing for ABPA would include serum IgE levels, Aspergillus-specific antibodies, Aspergillus skin testing, serum precipitins for Aspergillus, and CT of the chest to assess for bronchiectasis. In asthmatics, the presence of bronchiectasis affecting three or more lobes, centrilobular nodules, and mucoid impaction on the CT of the chest is highly suggestive of ABPA. Of note, the presence of high attenuation mucus is highly specific for ABPA.

The diagnosis of drug-induced eosinophilic pneumonia is based on exposure to a drug without any obvious other cause of eosinophilic pneumonia, and with the removal of that drug, eosinophilic pneumonia improves. The way a certain diagnosis can be made would be to re-challenge with the drug and see if the pulmonary involvement recurs, however, this is not practical in most clinical settings.

In acute eosinophilic pneumonia, the chest radiograph shows bilateral opacities and bilateral pleural effusions. Chest CT can show interlobular septal thickening. The BAL eosinophil count is greater than 25% with no significant peripheral eosinophilia. Pleural fluid is eosinophil-rich and exudative.

Elevated peripheral eosinophils are commonly seen in chronic eosinophilic pneumonia, along with a BAL eosinophil count frequently greater than 40%. The radiographic presentation of chronic eosinophilic pneumonia is usually peripheral bilateral alveolar opacities in nearly all cases, with about a fourth having migratory opacities. The classic pattern of " the photographic negative of pulmonary edema," is also seen only in about one-fourth of cases. Pleural effusions and adenopathy are rare.

In EGPA, ill-defined pulmonary opacities can be seen on chest x-ray, however often the chest x-ray can be normal. CT chest can show ground-glass opacities or consolidations that are peripheral or random in distribution. Peripheral eosinophilia is seen which can be significantly elevated, and an elevated BAL eosinophil count greater than 25% can be seen if there is active pneumonitis. ANCA positivity is seen in approximately 40% of cases, mainly perinuclear antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (p-ANCAs) with myeloperoxidase activity. The American College of Rheumatology uses four out of these six criteria to make a diagnosis of EGPA: asthma, peripheral eosinophilia greater than 10% of white count differential, neuropathy, pulmonary opacities, paranasal sinus abnormality, and a biopsy showing tissue eosinophilia. There may be a significant overlap between EGPA and CEP as they both occur in patients with prior asthma and atopy, with peripheral pulmonary opacities, peripheral eosinophilia, and BAL eosinophilia. Biopsy to make the diagnosis of EGPA is preferred, but not essential, in patients with characteristic clinical features and marked eosinophilia. A lung biopsy is not commonly done for the diagnosis due to the patchy involvement; instead skin, nerve, and muscle are sites where biopsies can be obtained with more ease.

Hypereosinophilic syndrome is diagnosed based on findings of persistent eosinophilia greater than 1.5 × 10 /L (1500/microliters) for longer than six months causing organ damage (heart failure, pulmonary fibrosis, hepatosplenomegaly, CNS involvement) without evidence for parasitic, allergic, or other known causes of eosinophilia. Pulmonary involvement is present in about 40% of patients, showing up as pleural effusions, pulmonary emboli, and interstitial opacities. BAL eosinophilia is usually mild and is not seen in all cases of HES.

If the patient is from an endemic area of parasites or traveled to certain locations, serology towards endemic parasites such as Strongyloides, Ascaris, Toxocara, etc. should be screened and a stool sample for ova and parasites. A positive serology would point towards a parasitic etiology of the eosinophilia but would not be confirmatory. Ascariasis is usually diagnosed by larvae in sputum or stool for ova and parasites within the time frame of pulmonary symptoms. Diagnosis of Strongyloidiasis depends on the demonstration of larvae in the feces or in sputum and BAL fluid. Both can have peripheral and BAL eosinophilia. Antibody testing for Strongyloides with ELISA can also be used for diagnosis. Transient pulmonary opacities may be seen on chest radiography.

Tropical pulmonary eosinophilia has significant peripheral eosinophilia and BAL eosinophilia and is diagnosed based on findings of a cough that is worse at night, residency in an endemic area, peripheral eosinophilia, and response to therapy with diethylcarbamazine.

Treatment / Management

The treatment of EP depends on the underlying etiology and is directed towards the alleviation of the underlying etiology. [11][12]

In a patient with risk factors and positive serology for parasites, an empiric trial of mebendazole can be given.

In acute EP, intravenous corticosteroids are started with rapid improvement, as early as 12 hours and within 48 hours in almost all cases, which is then followed by switching to oral steroids which are tapered over 2-4 weeks.

Chronic EP responds very well to corticosteroids, with an improvement in symptoms and the radiological opacities within days to weeks. There is no established dose of corticosteroids. However, prednisone can be started at 0.5mg/kg/day with most patients requiring prolonged treatment (greater than 6 months) because of relapse while decreasing below a daily dose of 10 to 15 mg/day of prednisone. Of note, only around 30% of the patients can be weaned off prednisone therapy in their lifetime.

In EGPA, corticosteroids are also the mainstay of therapy. Depending on the severity, patients can be given either pulse dose methylprednisolone or prednisone 1 mg/kg/day and tapered slowly over months. In severe disease or with multisystem involvement such as heart, kidneys, and gastrointestinal tract, cyclophosphamide can be used as steroid-sparing therapy.

In hypereosinophilic syndrome, Imatinib is a first-line therapy in patients with the myeloproliferative variant of HES. Corticosteroids may be used, especially in the “lymphocytic variant” of HES (with response in only about half of the patients). The anti-IL-5 antibody mepolizumab has recently been shown to be beneficial as a corticosteroid-sparing agent

For ABPA, oral corticosteroids are the mainstay of treatment, with recent evidence showing itraconazole gives added benefit. Steroids are tapered over a few months.

Diethylcarbamazine is the drug of choice for tropical pulmonary eosinophilia.

Ascariasis is treated with oral mebendazole or albendazole. Strongyloides is treated with ivermectin, even if only antibodies are found to be positive, due to the risk of hyperinflation in the future.

Differential Diagnosis

- Mediastinal lymphoma

-

- Mucormycosis

Prognosis

Acute EP often presents clinically like acute respiratory distress syndrome; however, with corticosteroids recovery is rapid with no significant clinical or imaging sequelae and no relapse after stopping corticosteroid treatment. In contrast, relapse is common with chronic EP, often requiring prolonged steroid courses.

In CEP, most patients require a prolonged steroid course and frequently relapse when steroid doses are decreased. Similarly, in EGPA, relapses are common, and asthma often persists. Patients with cardiac involvement due to EGPA have a poorer prognosis.

The survival for HES used to be limited, but now it has significantly improved up to 70% to 80% in 10 years. ABPA is variable and can recur after treatment. In some who have very frequent exacerbations, long-term steroids may be needed.

Pearls and Other Issues

Pulmonary eosinophilia is a syndrome of elevated eosinophils greater than 25% in BAL or significant peripheral eosinophilia with pulmonary infiltrates. Bronchoscopy with BAL is the most commonly used approach to make a diagnosis of PE.

The diagnostic approach would be based on history, physical, laboratory testing, and imaging. If the patient has exposure to an endemic parasitic area, then consider simple/tropical pulmonary eosinophilia. If there is a prior history of uncontrolled asthma, then consider ABPA. If multiple organs are involved, such as the heart, skin, and nerves, with vasculitic changes then consider EGPA. If acute ARDS is pictured, then consider AEP. If chronic bilateral peripheral pulmonary opacities are found, then consider CEP. If no obvious cause is found, then it can be drug-induced. There can be significant overlap in the presentation of CEP and EGPA.

Corticosteroids are the main choice of treatment in most pulmonary eosinophilic pneumonias such as AEP, CEP, ABPA, EGPA, and HES. Anti-parasitic agents are used for parasite-induced pulmonary eosinophilia. CEP and ABPA frequently return and need recurrent therapy.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

When patients present with pulmonary symptoms and have eosinophilia, one should consider acute eosinophilic pneumonia (AEP), chronic eosinophilic pneumonia (CEP), eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis (EGPA), and hypereosinophilic syndrome (HES). Secondary pulmonary eosinophilia occurs due to known causes, such as allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis (ABPA), parasites, medications, radiation effects, and malignancies. These patients should be referred to a pulmonologist for definitive workup. Once the diagnosis is made the patient may be followed by the primary care provider, physician assistant, or nurse practitioner. The outcomes depend on the cause.