Continuing Education Activity

Myopathies are a heterogeneous group of disorders primarily affecting the skeletal muscle structure, metabolism or channel function. They usually present with muscle weakness interfering in daily life activities. Muscle pain is also a common finding and some myopathies are associated with rhabdomyolysis. This activity reviews the classification, presentation patterns and highlights the role of interprofessional team in diagnosis and management of a suspected muscle disorder.

Objectives:

- Identify the presentation patterns of common myopathies.

- Describe the diagnostic approach of a suspected myopathy.

- Outline the management of a suspected myopathy.

Introduction

Myopathy is derived from the Greek words “myo” for muscle, and “pathy” for suffering which means muscle disease. The most common signs and symptoms of myopathies include weakness, stiffness, cramps, and spasms. Myopathies are a heterogeneous group of disorders primarily affecting the skeletal muscle structure, metabolism, or channel function. They usually present with muscle weakness interfering in daily life activities. Muscle pain is also a common finding and some myopathies are associated with rhabdomyolysis.

Etiology

The etiology of the myopathies is usually caused by a disruption in the muscle tissue integrity, and the metabolic stability which may be triggered by inherited genetic diseases, or metabolic errors, certain drugs and toxins, bacterial or viral infections, inflammation, besides minerals, electrolytes, and hormonal irregularities:

Inherited Myopathies

- Mitochondrial Myopathies[1]

- Mitochondrial encephalopathy, lactic acidosis, and strokelike syndrome (MELAS)

- Kearns-Sayre syndrome

- Others (Leber hereditary optic neuropathy; Myoclonic epilepsy with ragged red fibers; Leigh syndrome and neuropathy, ataxia, and retinitis pigmentosa; mtDNA deletion and depletion syndromes; Chronic progressive external ophthalmoplegia; etc.)[1]

- Congenital Myopathies

- Nemaline myopathies[2]

- Core myopathies

- Centronuclear myopathies

- Others[3]

- Metabolic Myopathies[4]

- Lipid myopathies (most common are carnitine palmitoyltransferase II deficiency, very-long-chain-acyl-CoA dehydrogenase deficiency, trifunctional protein deficiency)

- Glycogen storage disease myopathy (Acid maltase deficiency - Pompe disease, Debrancher deficiency - Cori disease - and muscle phosphorylase deficiency - McArdle disease - are the most frequently encountered)

- Channelopathies

- Periodic paralysis (Hypokalemic, hyperkalemic, Andersen-Tawil syndrome)

- Nondystrophic myotonias (p.e. paramyotonia congenita, Thomsen disease)

- Muscular Dystrophies[5]

- Dystrophinopathies (Duchenne muscular dystrophy, Becker muscular dystrophy, Intermediate phenotype)

- Myotonic muscular dystrophies (type 1 and type 2)

- Facioscapulohumeral muscular dystrophies (type 1 and type 2)

- Emery-Dreifuss muscular dystrophy

- Limb-girdle muscular dystrophies

- Oculopharyngeal muscular dystrophy

- Congenital muscular dystrophy (most common being LAMA2-related, collagen VI-related and alfa-dystroglycan-related)

- Distal myopathies

Acquired Myopathies

- Toxic Myopathies

- Necrotizing myopathies (statins, fibrates, immune checkpoint inhibitors, labetalol, propofol, alcohol, cyclosporine)[6][7]

- Mitochondrial myopathies (some antiretrovirals)

- Amphiphilic myopathies (chloroquine, hydroxychloroquine, amiodarone)

- Antimicrotubular myopathies (vincristine)

- Hypokalemic myopathies (diuretics, steroids, laxatives, alcohol, etc.)

- Critical care-associated myopathies (corticosteroids, neuromuscular blockers)

- Inflammatory myopathy (tumor necrosis alfa inhibitors, immune checkpoint inhibitors, statins, IFN-alfa, D-penicillamine, L-tryptophan, hydroxyurea, imatinib lamotrigine, phenytoin)

- Unknown mechanism (finasteride, omeprazole, isotretinoin)[7]

- Immune-mediated or Idiopathic Inflammatory Myopathies

- Dermatomyositis

- Antisynthetase syndrome

- Immune-mediated necrotizing myopathy

- Inclusion body myopathy

- Overlap myositis (association with other connective tissue diseases as systemic lupus erythematosus, Sjogren syndrome, systemic sclerosis, and rheumatoid arthritis)

- Polymyositis[8]

- Infectious Myopathies

- Bacterial infections (Lyme disease, pyomyositis - Staphylococcus aureus)

- Viral infections (Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), Coxsackie A and B viruses, Influenza)

- Parasitic infections (trichinosis, toxoplasmosis, cysticercosis)[9][10][11]

- Fungal infection (Candida, Coccidiomycosis)[8]

- Endocrine Myopathies [12]

- Thyroid and parathyroid dysfunction (hyperthyroidism, hypothyroidism, hyperparathyroidism)

- Adrenal dysfunction (Addison's disease, Cushing syndrome)

- Diabetic muscle infarction

- Electrolyte-mediated Mopathies (hypo- and hyperkalemia, hypercalcemia, hypermagnesemia, hypophosphatemia)

- Myopathies associated with systemic disease (amyloidosis, sarcoidosis, vitamin D deficiency, critical care myopathy, idiopathic eosinophilic myopathy, paraneoplastic)

NOTE: Rhabdomyolysis is a syndrome defined by skeletal muscle damage with CK elevation. It can occur with or without underlying muscle disease and should not be considered as a primary myopathy.[8]

Epidemiology

Inflammatory and endocrine myopathies are a more common type of myopathy in general which usually in middle-aged women> men. It was found that the incidence rate of inflammatory myopathies varied between 1.16 to 19/million/year while the prevalence varied between 2.4 to 33.8 per 100,000 population.[13]

The most common inherited myopathies are the dystrophinopathies, which are more common in male patients and affect every race and ethnicity equally. Amongst them, Duchenne's and Becker's muscular dystrophy are the most prevalent which varied between 19.8 and 25.1 per 100,000 person-years.[14] Mitochondrial myopathies affect 1 in 4300 people. Other forms of inherited myopathies are rare.[14]

History and Physical

Myopathies are typically involving motor impairment without no sensory symptoms. It presents as proximal muscle weakness, mainly in the pelvic girdle or the shoulder girdle muscle groups. However, pelvic muscle group is more common and more severe. Comprehensive history alongside physical examination is mandatory to identify and diagnose myopathies. Patients may complain of difficulty raising up from sitting position, climbing stairs or difficulty brushing their hair, or practicing any above head activities. Some other myopathies will present in different muscle groups like thighs, back muscles, or fingers, and could be possibly associated with other symptoms like myalgia, rashes, fatigue, or cramps. Muscle disease could also present with dark urine as a sign of renal damage in the case of rhabdomyolysis, particularly after vigorous exercises like running marathons.

Polymyositis and dermatomyositis: Both of them affect women more than men, present with proximal weakness affects pelvic girdle more than shoulder girdle. Polymyositis is associated with arthralgia while dermatomyositis is associated with other symptoms mainly skin manifestations including a purple rash on the eyelids called heliotrope rash, an erythematous scaly rash appears on the dorsum of the fingers called Gottron's papules, a reddish rash appears on the shoulder and the back known as Shawl sign, besides interstitial lung disease, Gastrointestinal vasculitis, and paraneoplastic syndrome underlying malignancy.[15]

Hypothyroid and hyperthyroid myopathies: Both of them are associated with the thyroid disease whether it is hypo- or hyperthyroid disease, and both present with proximal muscle weakness and peripheral neuropathy. Hypothyroid myopathy is associated with pseudohypertrophy, myoedema, and delayed deep tendon reflexes. Hyperthyroid myopathy is associated with Grave's ophthalmopathy, goiter, and extraocular muscle weakness as well.[12][16][12]

Other types of acquired myopathies will represent within a group of symptoms associated with that particular disease like for example sarcoidosis myopathy, amyloid myopathy, and critical illness myopathy. Duchenne muscular dystrophy, myotonic dystrophy 1,2, mitochondrial myopathies, Glycogen storage diseases like (McArdle, Pompe's disease, etc) are inherited myopathies affect children and it is rare, and accompanied with severe systemic complications. These patients' life expectancy is relatively limited depending on the severity of the disease and the complications.[17]

Evaluation

The complementary evaluation should be guided by clinical suspicion. Useful tests include:

1) Laboratory studies

- Complete blood count

- Blood urea nitrogen and serum creatinine

- Electrolytes (sodium, magnesium, potassium, calcium, phosphorus)

- Aspartate aminotransferase (AST), alanine aminotransferase (ALT), lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), y-glutamyltransferase (GGT)

- Creatine kinase (CK), myoglobin, and aldolase: CK the most useful blood test but levels may not correlate with the degree of muscle weakness. Myopathies with enhanced regeneration or spared myofibers, such as in antisynthetase syndrome, dermatomyositis, and critical care myopathy, may present with normal CK and selectively elevated aldolase.

- C-reactive protein and erythrocyte sedimentation rate

- Thyroid function tests

- Anti-nuclear antigen (ANA) and myositis associated antibody panel (importantly -Jo1, -PL7, -PL12, -OJ for antisynthetase syndrome; TIF1-gamma, - NXP2, -Mi2, -SAE, - MDA5 for dermatomyositis, - HMG-CoA, -SRP for immune-mediated necrotizing myopathy)

- Urinalysis: positive hemoglobin dipstick without erythrocytes on microscopic evaluation is a sign of myoglobinuria

2) Electromyography (EMG) and nerve conduction study (NCS):[8]

In this context electrodiagnostic testing has many objectives:

- it is useful to exclude alternative diagnoses such as neuromuscular junction or motor neuron disorders.

- it can confirm the myopathic nature of the process if there is an identifiable pattern.

- it helps characterized and stratify the severity of the disease

- it can help to choose the best location to perform a muscle biopsy.

Motor NCS are usually normal unless there is a concomitant neuropathy. Exceptions to this include distal myopathies and critical care myopathy where low compound muscle action potentials (CMAPs) with normal latencies and conduction velocities are seen. Sensory NCS are within normal range...Inclusion body myositis is the exception since it can cause sensory abnormalities.

Needle EMG is the most sensitive examination for myopathy. The presence of myotonic discharges and muscle membrane irritability (increased insertional activity, fibrillation potentials, and positive sharp waves) helps to narrow the differential diagnosis as it is generally present in necrotizing myopathies (inflammatory or toxic), myotonic dystrophies and a few metabolic and congenital myopathies. Repetitive stimulation and correlation with exercise may be needed in the special case of channelopathies.

Complex repetitive discharges and decreased insertional activity are signs of a chronic process.

In some metabolic, congenital, endocrine myopathies, electrodiagnostic tests may be normal.

Of note, electrodiagnostic testing is not always needed if there is a strong suspicion of a myopathic disorder (p.e. suggestive clinical features with elevated CK or positive family history), especially in the pediatric population. [18]

3) Electrocardiography (ECG): Findings suggestive of hypokalemia include the following:

- Diffuse nonspecific ST-T wave changes

- Increased PR interval

- U waves

- Wide QRS

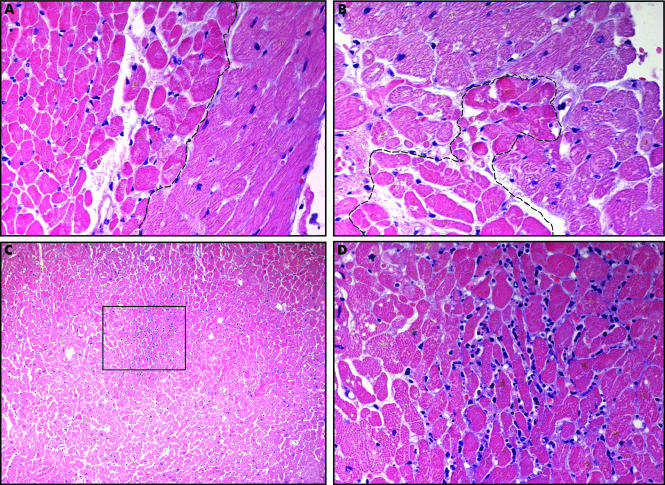

4) Muscle biopsy: Muscle biopsies are categorized by three major components:[8]

- Histological/histochemical

- Myopathic vs. neuropathic patterns of disease

- Presence of unique features that are clues to underlying pathophysiology and diagnosis

- Myopathic pattern

- Rounding and variation of myofiber size

- Internal nuclei, fiber atrophy, degeneration and regenerating myofibers

- Fatty replacement

- Neuropathic pattern

- Evidence of denervation and re-innervation

- Small, atrophic, angular fibers and target fibers

- Re-innovation results in fiber type grouping

5) Muscle MRI: Magnetic resonance imaging of the muscles:[8]

- Increased signal intensity within muscle tissue

- May see muscle necrosis, degeneration, and/or inflammation

- May see fatty replacement, an indicator of chronic muscle damage

- Findings may help guide site selection for muscle biopsy

- MRI offers a less invasive assessment tool in pediatric populations

Treatment / Management

Treatment for myopathy is generally supportive due to the nature of the etiology of the muscle disease including exercises, physical and occupational therapies, nutrition, and dietetics, and may be genetic analysis and counseling.[19][20]

Inherited muscular dystrophies: Prednisone 0.75 mg/kg/day has presented improvement in muscle strength, increased muscle bulking, and slowed the disease progression. It is also important to anticipate complications and treat them accordingly. In mitochondrial myopathies creatine monohydrate 5-10 g/day may benefit improving the symptoms, Coenzyme Q10 replacement still needs more consistent research results to prove significance.[21][18][21]

Acquired myopathies, in general, improve by treating the main causing disease whether it is a systemic disease like thyroid disease, sarcoidosis. Some acquired myopathies will be caused by infection ( Bacterial, Viral, Fungal, Parasitic, or spirochetes) the myopathy symptoms improve by treating the infection. Toxin or drug-related myopathy is also managed by the removal of the causative agent and avoiding it in the future. HIV-related myopathy is also responding well to antiretroviral therapy HAART, and maybe steroids as well.[22][18]

Inflammatory myopathy and autoimmune related myopathies are treated mainly by immunomodulatory, immunosuppressants, and steroid drugs. It is proved that steroids are better in comparison to immunomodulatory drugs due to side effects. Medications used are methotrexate, azathioprine, cyclosporin, and cyclophosphamide besides oral dexamethasone and daily oral prednisolone. Unfortunately, some cases including IBMs are refractory to immunosuppressants medication and steroids, and they continue to progress to more generalized weakness. High quality Randomised clinical trials are needed to determine the effectiveness and toxicity of the immuno-mediated drugs in the treatment of these inflammatory myopathies.[23]

Rhabdomyolysis: The ultimate goal for treatment in rhabdomyolysis is preventing the acute kidney injury by the myoglobin resulting from the muscle damage. Aggressive hydration by IV fluids, and closely monitoring the kidney functions, and the electrolyte balance.[18]

Differential Diagnosis

Differential diagnosis of myopathy is extensive, as it varies depends on the associated symptoms:

Guillain-Barre syndrome: The typical patient with GBS, which in most cases will manifest as acute inflammatory demyelinating polyradiculoneuropathy (AIDP), presents 2-4 weeks following a relatively benign respiratory or gastrointestinal illness with complaints of finger dysesthesias and proximal muscle weakness of the lower extremities. The weakness may progress over hours to days to involve the arms, truncal muscles, cranial nerves, and muscles of respiration.

Tick-borne diseases: The reference standard for the diagnosis of tickborne rickettsial diseases is the indirect immunofluorescence antibody (IFA) assay using paired serum samples obtained soon after illness onset and 2-4 weeks later.

Lambert-Eaton myasthenic syndrome (LEMS): proximal muscle weakness, depressed tendon reflexes, post-tetanic potentiation, and autonomic changes due to impairment in acetylcholine release.

Myasthenia gravis: an autoimmune disorder of peripheral nerves in which antibodies form against acetylcholine (ACh) nicotinic postsynaptic receptors at the myoneural junction. A reduction in the number of ACh receptors results in a characteristic pattern of progressively reduced muscle strength with repeated use of the muscle and recovery of muscle strength following a period of rest. The bulbar muscles are affected most commonly and most severely, but most patients also develop some degree of fluctuating generalized weakness.

Other differentials include the following:

- Malignant hyperthermia

- Myotonia

- Myositis ossificans

- Myositis associated with the vasculitides

- Paraneoplastic syndromes (eg. carcinomatous neuropathy, cachexia, myonecrosis)

- Direct muscle damage (trauma, excessive exercise)

- Nutritional deficiencies (vitamin E deficiency, malabsorption syndromes)

Prognosis

The treatment goals for most myopathies are to slow or stop the progression of the disease concerning congenital, metabolic, and inflammatory myopathies. Some of the inherited myopathies' complications could be fatal. The health-related quality of life within this category of myopathies such as inflammatory and congenital myopathies is impaired. However. the prognosis of acquired myopathies is dependant on the etiology whether it is the severity of the systemic disease or the nature of the infection, and the damage occurred due to a drug or a toxin. The acquired myopathies are well controlled by treating the main disease.[24]

Complications

The complications of the various types of myopathies are largely attributed to the progression of the disease. Congenital, metabolic and hereditary myopathies could have fatal complications like cardiomyopathies, recurrent infections, and sepsis, neuropathies, respiratory failure, or renal failures. On the other hand, the complications of acquired myopathies are relatively limited to the etiology. For example, if it is infectious related then it is dependant on the type of the infection or if it is related to drug or toxin, then it is dependant on the dose and the period, and so on. Here is a list of possible complications:

- Death

- Rhabdomyolysis

- Heart arrhythmias

- Paraneoplastic syndromes

- Heart failure

- Hypertension

- Renal failure

- Neuropathies: Seizures and cerebral dysplasias

- Impaired movement

- Bedsores

- Infections and sepsis

- Irreversible muscle wasting

- Recurrent dysphagia

- Acute gastric dilation

- Respiratory system failure

- Endocrinopathies

- Cataracts

- Sensorineural hearing loss[25][26][27]

Deterrence and Patient Education

Some of the myopathic diseases are chronic and require lifestyle modification. It is highly encouraged to maintain a balanced diet that contacts a variety of fruits and vegetables. In addition to a balanced diet, it is essential to stay active. Physical therapy and moderate exercise plans are recommended. Particularly in patients with metabolic myopathies like lysosomal storage disease and glycogen storage disease, etc.. are encouraged to follow moderate exercise plans besides diet plans that focus on decreasing the causative diet components.

Inflammatory muscle diseases are chronic diseases. Patients tend to benefit from regular exercise plans alongside medical therapy. Patients are advised to continue to monitor the progression of the disease and the severity of the symptoms and maintain continuous medical care. Inherited myopathies are usually associated with other complications. Anticipating complications is vital in the survival rate, and seeking immediate medical care in cases of emergencies like cardiomyopathies, sepsis. etc.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Myopathies management is highly dependant on an interprofessional team of primary care physicians, family physicians, pediatricians, neurologists, rheumatologists, nephrologists, cardiologists, and even orthopedics. There are also other health care providers that have a great share for the care of this cohort of myopathic patients include dietitians, nutritionists, genetic counselors, mental health counselors, physical therapists, occupational therapists, and speech therapists. It is pivotal to maintain interprofessional communication between all treatment team to slow the progression of different myopathies.

While the primary care physician or the family physician might be the first person who encounters the patient diagnosis with one of the chronic myopathies, it takes all other specialists to participate in the treatment plans alongside with other medical providers mentioned above. The ultimate outcome to slow the progression of the disease and help patients with inherited myopathies to cope with the disease and to delay the onset of the complications. The multi-professional treatment team together improves the health-related quality of life for myopathic patients.