Continuing Education Activity

One of the most common reasons for clinical visits in the United States is sinusitis, also known as rhinosinusitis. It is also one of the top reasons that antibiotics are prescribed. Over 1 year, there were up to 73 million restricted-activity days related to sinusitis and total direct medical costs of almost 2.4 billion, not including surgery or radiographic imaging. In addition, up to 14.7 percent of individuals surveyed in the National Health Interview Survey reported having had sinusitis the preceding year. This activity reviews the cause, presentation, and pathophysiology of sinusitis and highlights the role of the interprofessional team in its management.

Objectives:

Identify exam findings consistent with rhinosinusitis.

Assess the management of rhinosinusitis.

Evaluate complications of rhinosinusitis.

Communicate why an interprofessional approach is imperative to effectively managing patients with rhinosinusitis.

Introduction

Sinusitis is 1 of the most common health complaints leading to a physician visit in the United States and 1 of the leading causes of antibiotic prescriptions. In 1 year, there were up to 73 million restricted activity days in patients with sinusitis and total direct medical costs of almost $2.4 billion (not including surgery or radiographic imaging). In addition, up to 14.7% of people in 1 National Health Interview Survey had sinusitis the preceding year. The newer term is rhinosinusitis because purulent sinus disease without similar rhinitis is rare.

Four classifications of rhinosinusitis:

- Acute rhinosinusitis: Sudden onset, lasting less than 4 weeks with complete resolution.

- Subacute rhinosinusitis: A continuum of acute rhinosinusitis but less than 12 weeks.

- Recurrent acute rhinosinusitis: Four or more acute episodes lasting at least 7 days each, in any 1-year period.

- Chronic rhinosinusitis: Signs of symptoms persist for 12 weeks or longer.

Etiology

Causes are a combination of environmental and host factors. Acute sinusitis is most commonly due to viruses and is usually self-limiting (see Image. Acute Sinusitis). Approximately 90% of patients with colds have an element of viral sinusitis. Those with atopy commonly get sinusitis. Allergens, irritants, viruses, fungi, and bacteria can cause it. Popular irritants are animal dander, polluted air, smoke, and dust.

Epidemiology

There are higher rates of sinusitis among women in the South and Midwest. Children younger than 15 years of age and adults aged 25 to 64 years are affected the most.[1]

Other risk factors for sinusitis include:

- Anatomic defects such as septal deviations, polyps, conchae bullosa, other trauma, and fractures involving the sinuses or the facial area surrounding them

- Impaired mucous transport from diseases such as cystic fibrosis, ciliary dyskinesia

- Immunodeficiency from chemotherapy, human immunodeficiency virus, diabetes mellitus, etc

- Body positioning in intensive care unit patients due to prolonged supine positioning compromises mucociliary clearance.

- Rhinitis medicamentosa, toxic rhinitis, nasal cocaine abuse, barotrauma, foreign bodies

- Prolonged oxygen use due to drying of the mucosal lining

- Patients with nasogastric or nasotracheal tubes [2]

Pathophysiology

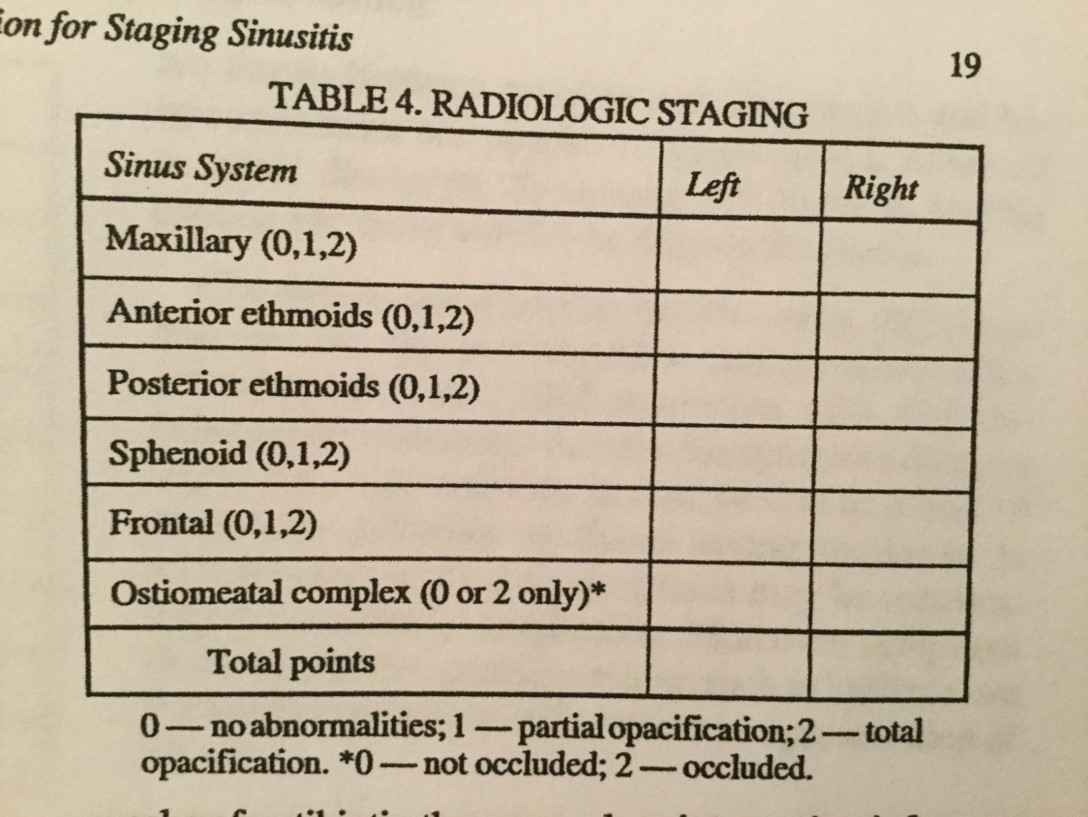

A viral upper respiratory infection commonly causes rhinosinusitis secondary to edema and inflammation of the nasal lining and the production of thick mucus that obstructs the paranasal sinuses and allows a secondary bacterial overgrowth. There are frontal, maxillary, sphenoid, and ethmoid sinuses (see Image. Lund-Mackay Scoring System for Staging Sinusitis). Allergic rhinitis can also lead to sinusitis due to ostial obstruction. Ciliary immobility can lead to increased mucus viscosity, further blocking drainage. Bacteria are introduced into the sinuses by coughing and nose blowing. Bacterial sinusitis usually occurs after a viral upper respiratory infection, with worsening symptoms after 5 days or persistent symptoms after 10 days.

Histopathology

Tissue and culture results reveal:

- Fifteen percent of aspirates contain viruses

- Streptococcus pneumoniae 3%, Haemophilus influenzae 21%, anaerobes 6%, Staphylococcus aureus 4%, Streptococcus pyogenes 2%, Moraxella 2%

- Chronic: S. aureus 20%, anaerobes 3%, S. pneumoniae 4%, multiple organisms 16%

- Fungal incidence is 2% to 7%, most commonly Aspergillus and most commonly seen in immunocompromised patients [3]

History and Physical

Major factors include facial pain/pressure, congestion/fullness, nasal obstruction, nasal or postnasal purulence, hyposmia, and fever. Minor factors (diagnostically significant only with 1 or more major factors) include a headache, halitosis, fatigue, malaise, dental pain, cough, and otalgia. A physical exam is best performed after a topical decongestant. On exam, look for facial swelling, erythema, edema (most commonly periorbital), cervical adenopathy, postnasal drainage, or pharyngitis. Anterior rhinoscopy may reveal mucosal edema, mucous crusting, frank purulence, obstructive polyps, or other anatomical defects. Percuss the forehead and cheeks for deep tenderness. Transillumination of the sinuses may be helpful. There are 5 independent predictors of sinusitis: maxillary dental pain, abnormal sinus transillumination, poor response to nasal decongestants or antihistamines, colored nasal discharge, and mucopurulent, seen on examination. The presence of 4 or more is highly predictive of sinusitis. The overall impression of the examining physician may be more accurate than any single finding.[4]

Evaluation

No laboratory tests are indicated in the emergency department for acute uncomplicated sinusitis because the diagnosis is usually clinical. A plain sinus X-ray may detect the maxillary, frontal, or sphenoid disease but is not useful for evaluating the anterior ethmoid cells or the ostiomeatal complex from which most sinus disease originates. Positive findings on plain films are air-fluid levels, sinus opacity, or mucosal thickening of 6 mm or more. Coronal CT at a thickness of 3 mm to 4 mm is the modality of choice. The CT findings suggest sinusitis is sinus opacification, air-fluid levels, sinus wall displacement, and 4 mm or greater mucosal thickening.[5] Culture and biopsy are indicated for chronic bacterial and fungal sinusitis.[6]

Treatment / Management

Humidification, nasal wash, decongestants (topical or systemic) such as pseudoephedrine. Remember that oxymetazoline cannot be used for more than 3 days due to rebound congestion and that oral decongestants should be used with caution in hypertensive patients. Antihistamines are not useful and can lead to impaired drainage. They are only of benefit in early allergic sinusitis. Topical steroids diminish nasal mucosal edema but are more efficacious in chronic and allergic sinusitis. Only start antibiotics if you strongly suspect bacterial disease.[7]

Antibiotics: Use empirically and based on community patterns of resistance. Ten to 14 days of amoxicillin or amoxicillin-clavulanate is the first-line treatment. In some communities, amoxicillin effectiveness is less than 70%. Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole works well for some, but there is a higher resistance rate. Failure of symptoms to resolve after 7 days of therapy should prompt one to switch to a broader spectrum agent, such as 10 to 14 days of amoxicillin-clavulanate, cefuroxime axetil, other second or third-generation cephalosporins, clindamycin alone or along with ciprofloxacin, sulfamethoxazole, a macrolide, or 1 of the fluoroquinolones.[8] Metronidazole may be added to any of these agents to increase anaerobic coverage. Antibiotics should cover S. aureus for chronic sinusitis and be effective against the higher incidence of beta-lactamase-producing organisms that are common in chronic disease. If the patient is not improving after 5 to 7 days, add metronidazole or clindamycin. Adults who respond to treatment should be treated for 5 to 7 days. Children should be treated for 10 to 14 days.

Differential Diagnosis

The most common malady mistaken for sinusitis is rhinitis or an upper respiratory infection. A maxillary toothache can also mimic the pain caused by maxillary sinusitis. Tension headaches, vascular headaches, foreign bodies, brain abscesses, epidural abscesses, meningitis, and subdural empyema can also be mistaken for sinusitis.[9]

Prognosis

Most uncomplicated acute bacterial sinusitis cases can be treated as an outpatient with a good prognosis. Frontal or sphenoid sinusitis with air-fluid levels may require hospitalization with intravenous antibiotics. Patients who are immunocompromised or are toxic appearing require admission. Fungal sinusitis is associated with high morbidity and mortality.[10]

Pearls and Other Issues

Sinusitis may extend to the bones and soft tissues of the face and orbits. Facial cellulitis, periorbital cellulitis, orbital abscess, and blindness can develop. Sinusitis can lead to intracranial complications such as cavernous sinus thrombosis, epidural or subdural empyema, and meningitis.[11][12]

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Sinusitis is a common disease best managed by an interprofessional team that includes nurses and pharmacists. The key to treatment is reducing the triggers. Patients should be urged to quit smoking. In addition, the early empirical use of antibiotics should be avoided. The outcomes depend on the cause, but despite treatment, recurrences are common and lead to poor quality of life.